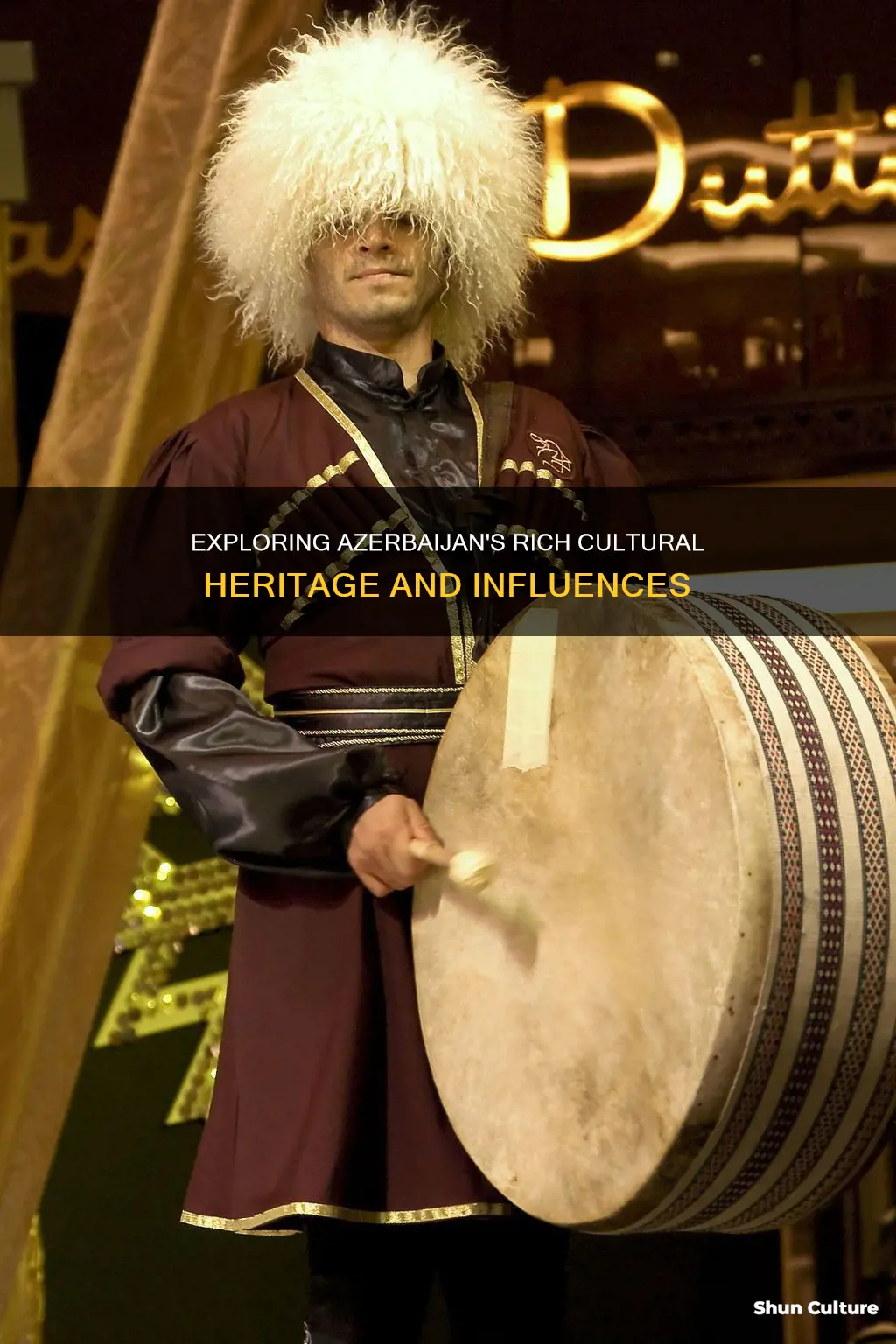

Azerbaijan's culture is a blend of influences from Iran, Turkey, Russia, and the West, with its roots in the nomadic traditions of warring Turkic tribes, sedentary Persian lifestyles, and Arab-Islamic ideology. The country's cultural delights range from its cuisine to its crafts, natural beauty, architecture, music, and arts.

Azerbaijan's official language is Azerbaijani, which belongs to the Turkic family of languages, and most residents also speak Russian as a second language. The country follows Shia Islam, like neighbouring Iran, and has good relations with Israel, which is unusual in the Islamic world.

Azerbaijan's rich and diverse cultural history is reflected in its striking landscapes, where the past and present blend to create memorable vistas. The capital, Baku, lies on the shores of the Caspian Sea and boasts UNESCO World Heritage Sites, modern architectural marvels, and one of the world's oldest continuously burning fires, Yanar Dag, just outside the city.

Azerbaijani culture is also known for its tea-drinking rituals, unparalleled hospitality, and colourful dances, music, and textiles, especially rugs. The country's ancient roots are evident in its medieval palaces, durable Soviet structures, and record-setting skyscrapers.

With its unique and fascinating blend of cultural influences, Azerbaijan offers visitors a wide range of genuine and unforgettable experiences.

What You'll Learn

Azerbaijan's Zoroastrian fire temples

Zoroastrianism has left a deep mark on the history of Azerbaijan, with the country's name being attributed to the Persian word for fire, "azar", because of the popularity of Zoroastrianism in the region. Zoroastrianism is one of the world's oldest religions and was practised in the territory of Azerbaijan in ancient times.

The Ateshgah of Baku, often called the "Fire Temple of Baku", is a castle-like religious temple in Surakhany, a suburb of Baku, Azerbaijan. The pentagonal complex, which has a courtyard surrounded by cells for monks and a tetrapillar-altar in the middle, was built during the 17th and 18th centuries. The temple was used as a Hindu, Sikh, and Zoroastrian place of worship. The name Ateshgah means "home of fire" in Persian. The temple was a pilgrimage and philosophical centre for Zoroastrians from Northwestern India, who were involved in trade with the Caspian area. The four holy elements of their belief were fire, air, water, and earth.

The Zoroastrian temple was destroyed following the introduction of Islam, and many Zoroastrians left for India, where they continued their worship. However, in the 15th to 17th centuries, Hindu fire worshippers who came to Absheron with trading caravans began to make pilgrimages to Surakhany. The Indian merchants started to build the temple, and the earliest part is dated to 1713. The latest part, the central temple altar, was built with the support of merchant Kanchangar in 1810. During the 18th century, chapels, cells, and a caravanserai were added to the temple's central part. The temple features carved inscriptions in Indian lettering.

In the mid-19th century, the natural gas yield ceased due to the movement of the surface, which pilgrims interpreted as punishment from the gods, and they left. The temple ceased to be a place of worship after 1883, with the installation of petroleum plants at Surakhany. The complex was turned into a museum in 1975 and was designated a state historical-architectural reserve by decree of the President of Azerbaijan in 2007.

Exploring Azerbaijan's Gulab: A Cultural and Historical Journey

You may want to see also

The country's unique tea-drinking customs

Azerbaijan has a rich and unique tea culture, with tea drinking traditions that are embedded in the country's history and daily life. Tea is an essential part of Azerbaijani culture and hospitality, and it is customary to offer tea to every visitor, no matter how short the visit. Tea is served at the beginning of a meal and is accompanied by various sweets, fruit jams, and sliced lemon. It is also common to add thyme, mint, or rose water to tea, which is believed to be good for the stomach and heart.

The traditional tea vessel in Azerbaijan is the "armudu" or "pear-shaped" glass, which is easy to hold due to its wider top and prevents the drinker from burning their hands. Tea is typically served in crystal or any other glasses or cups, and water is boiled in heated metal containers called samovars.

The Azerbaijani tea ceremony has its own rules and practices, and tea is served continuously when there are guests or interesting conversations. Tea is associated with warmth and friendliness, and it is considered impolite to let a guest leave without offering them at least one cup of tea.

In the past, tea production was one of the main industries in Azerbaijan, with the Lankaran-Astara region being the main area for tea cultivation. Today, tea is consumed at any time of the day or night in Azerbaijan, and traditional tea houses called "chaykhana" can be found in every corner of the country.

Azerbaijani tea culture also extends to matchmaking rituals. After the negotiations are complete, the maid will bring out tea, and the presence or absence of sugar indicates the chances for a marriage agreement.

Ivanka Trump's Azerbaijan Business Interests: Ethical?

You may want to see also

The importance of hospitality in Azerbaijani culture

Hospitality is a key part of Azerbaijani culture, with guests considered sacred. The great 12th-century Azerbaijani poet Nizami Ganjavi often returned to the noble custom of hospitality in his works. In his poem 'Yeddi Gozel' (The Seven Beauties), he writes:

> She was welcoming as a garden flower, Her smile was the bud of a rose. Her palace was prepared for guests And it reached to the skies. She laid a table and arranged a celebration, Her servants were raised in grace.

Hospitality is deeply rooted in the everyday life of the Azerbaijani people. Every household in Azerbaijan believes it is their duty and a matter of honour to receive their guest with great respect, entertain them and see them off. This applies not only to friends and acquaintances but also to strangers and travellers.

In Azerbaijan, hospitality is elevated to a moral quality and an internal instinct. Regardless of whether the guest is personally invited or not, they are considered a personal guest and treated with the utmost respect. Hosts will go to great lengths to accommodate their guests, sometimes even beyond their economic means. Guests are offered food, a room, and a bed, and it is customary to lay a banquet in their honour.

The custom of hospitality is so important that it is considered a distinctive feature of the Azerbaijani people. It is deeply ingrained in their culture, with children brought up to respect guests and to treat them with sincerity.

The guest is always put first in Azerbaijan. Even if an enemy steps into one's house, no retribution may be exacted as the guest is considered untouchable. The host will even set a guard to protect a guest whose life is in danger and will suggest that the guest prolongs their stay.

Hospitality is also extended to passers-by and travellers, who are offered food, a place to stay, and even a guide to help them on their journey.

The tradition of hospitality in Azerbaijan is so strong that it has survived through the centuries. Historical accounts from visitors to the country often mention the high level of hospitality they experienced. For example, the 17th-century Dutch traveller Jan Struys wrote about how he was welcomed into the homes of the local people during the Novruz holiday.

Hospitality is a valued national characteristic of Azerbaijan, and it is considered a typical Azeri trait.

Finding Love in Azerbaijan: A Guide for Men

You may want to see also

The country's literary history

Azerbaijan's literary history is a rich tapestry, influenced by its neighbouring countries and the empires that ruled the region. The earliest development of Azerbaijani literature is closely associated with Anatolian Turkish, written in Perso-Arabic script, with examples of its detachment dating back to the 14th century or earlier.

The Two Traditions of Azerbaijani Literature

Azerbaijani literature can be divided into two distinct traditions: Azerbaijani folk literature and Azerbaijani written literature. The salient difference between the two is the variety of language employed. The folk tradition was primarily oral and remained separate from Persian and Arabic literary influences. In contrast, the written tradition embraced these external influences.

Azerbaijani folk poetry—the dominant genre within the folk tradition—employed quantitative verse (syllabic verse) and used the quatrain as its basic structural unit. It was also intimately connected with song, with most poems being composed to be sung.

Azerbaijani Folk Literature

Azerbaijani folk literature is an oral tradition with its roots in Central Asian nomadic customs. However, its themes reflect the issues faced by a settling people who have abandoned the nomadic lifestyle. For example, the series of folktales surrounding Keloğlan, a young boy struggling to find a wife, maintain his family home, and deal with problematic neighbours. Another well-known figure from Azerbaijani folklore is Nasreddin, a trickster who plays jokes on his neighbours.

There are three basic genres within the folk tradition: the epic, folk poetry, and folklore. The Book of Dede Korkut is a key element of the Azerbaijani epic tradition, alongside the Turkic Epic of Köroğlu.

Azerbaijani Written Literature

Several major authors helped develop Azerbaijani literature from the 14th century until the 17th century, with poetry featuring prominently in their works. Towards the end of the 19th century, popular literature such as newspapers began to be published in the Azerbaijani language.

Azerbaijani written literature was heavily influenced by Persian and Arabic literature. This influence can be seen as far back as the Seljuk period (late 11th to early 14th centuries), where official business was conducted in Persian rather than Turkic, and court poets wrote in a language infused with Persian.

With the founding of Safavid Iran in the 16th century, standard poetic forms were derived from Persian literary tradition or indirectly through Persian from Arabic. As a result, the poetic meters of Persian poetry were adopted, and Persian- and Arabic-based words were brought into the Azerbaijani language. This style of writing became known as "Divan literature".

Soviet Rule

During Soviet rule, particularly under Joseph Stalin, Azerbaijani writers who did not conform to the Communist Party line were persecuted. Writers who did conform became mouthpieces for Soviet propaganda. However, some writers resisted and turned to clandestine methodologies of Sufism as a means of resistance.

Post-Soviet Literature

After gaining independence in 1991, Azerbaijani literature played an important role in promoting the liberation of occupied territories, love for the Motherland, and justice. Notable books from this period include "Karabakh – Mountains Call Us" by Elbrus Orujev and "Azerbaijan Diary: A Rogue Reporter's Adventures in an Oil-Rich, War-Torn, Post-Soviet Republic" by Thomas Goltz.

Notable Authors

- Manisa Khatun Mehseti Genjevi (11th century)

- Nizami Genjevi (12th century)

- Mirza Feteli Akhundov (19th century)

- Seyid Azim Shirvani (19th century)

- Mirza Alekber Sabir (19th/20th century)

- Jalil Mammadguluzadeh (20th century)

- Huseyn Javid (20th century)

- Ilyas Mahammad oglu Afandiyev (20th century)

- Natig Rasulzadeh (contemporary)

- Gholam-Hossein Sa'edi (contemporary)

- Nariman Karbalayi Najaf oglu Narimanov (20th century)

- Ahmad Javad (20th century)

- Vagif Samadoghlu (20th century)

- Mammad Araz (contemporary)

Exploring Baku: Azerbaijan's Captivating Capital

You may want to see also

The influence of religion on Azerbaijan's culture

Azerbaijan is a secular state with a rich and diverse cultural history. The country's culture combines a diverse and heterogeneous set of elements, influenced by Iranic, Turkic, and Caucasian cultures.

Islam is the majority religion in Azerbaijan, with 93-99% of the population identifying as Muslim. The country is considered the most secular in the Muslim world, with relatively low religious observance and a tendency to base Muslim identity on culture and ethnicity rather than religious practice. Shia Islam is the dominant branch, practised by 60-65% of Muslims, while 35-40% are Sunni Muslims. Shia Islam is prevalent in the western, central, and southern regions, with villages around Baku and the Lankaran region considered Shia strongholds. Sunni Islam is dominant in the northern regions.

The Azerbaijani constitution ensures freedom of religion, and the country is home to several religious minorities, including Christians (3.1-4.8% of the population), Jews (0.2%), and Baháʼís.

Zoroastrianism has a long history in Azerbaijan, dating back to the first millennium BC, and the country's name, "Land of Eternal Fire," is said to be linked to this religion. Zoroastrianism is still popular among the local people, and Novruz, a Zoroastrian holiday, is considered one of the most respected holidays in Azerbaijan.

Christianity has a long history in Azerbaijan as well, dating back to the first years of the Apostolic era. The country is home to both Orthodox and Catholic churches, with five operating Orthodox churches in Baku alone.

Judaism is represented in Azerbaijan by three separate communities: Mountain Jews, Ashkenazi Jews, and Georgian Jews, with a total population of almost 16,000. Baku is home to six of the country's ten synagogues, and the city's synagogue opened in 2003 is considered one of the largest in Europe.

The Baháʼí Faith in Azerbaijan has a complex history, with followers of its predecessor religion, Bábism, established in the country as early as 1850. The Baháʼí community was almost ended during the Soviet era but was reactivated in the 1990s, and today there are about 2,000 Baháʼís in the country, most of them in Baku.

While religion plays a relatively small role in politics and everyday life in Azerbaijan, the country's cultural life is deeply influenced by its religious diversity, with major holidays and traditions rooted in Zoroastrian, Christian, and Islamic traditions.

Azerbaijan: A Fragmented State? Exploring the Country's Complexities

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mugham, Azerbaijan's best-known type of music, features a singer accompanied by musicians playing local instruments such as the tar (a long-neck lute), kamancha (a four-string spiked fiddle) and the daf (a large tambourine). It is inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List.

Azerbaijan's dances are often choreographed to tell stories from the country's history, from graceful wedding dances to dances based on high-speed martial arts.

Azerbaijan's architecture is a blend of old and new, with ultra-modern Flame Towers standing guard over medieval masterpieces like Baku's Icheri Sheher (Inner City).

Azerbaijan's cuisine is influenced by its history, with traditional dishes similar to those of Iran and Turkey. The food relies heavily on fresh herbs, vegetables, and both saltwater and freshwater fish.