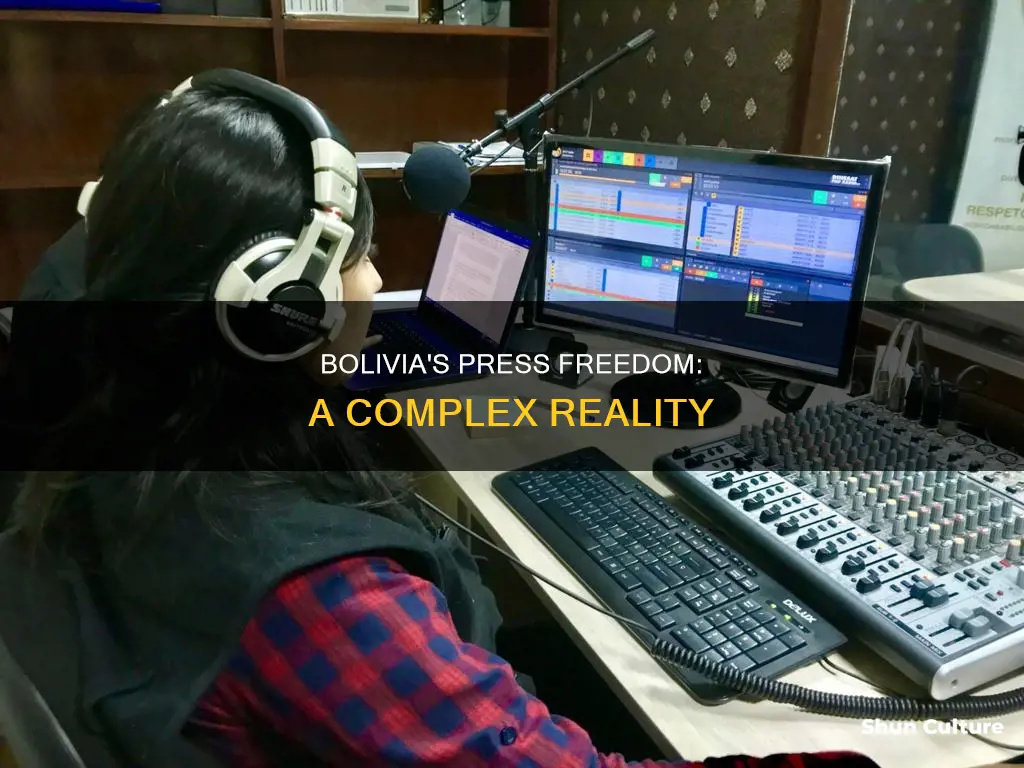

Bolivia's press freedom has been a topic of debate for several years. While the country's constitution protects freedom of speech and press, it also allows for some limitations. Bolivia's 2009 constitution established four branches of government: legislative, executive, judicial, and electoral, which oversees elections nationwide. The country's press freedom has been a point of contention, with some arguing that the government and its supporters constantly violate press freedom through attacks, threats, censorship, and harassment. Bolivia's press freedom index declined to 48.88 in 2024, ranking among the worst in Latin America. The country's regulatory framework has been criticised for limiting media freedom, and journalists have faced threats and physical attacks. The government controls many newspapers and has a strong influence on privately-owned media, which can jeopardise pluralism and lead to self-censorship. However, in recent years, attacks on journalists have decreased, and the judicial system has upheld the constitutional freedom of the press in some cases.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Freedom of the press ranking | 94 out of 180 countries |

| Freedom of the press score | 47 out of 100 |

| Press freedom index in 2023 | 51.09 |

| Press freedom index in 2022 | 47.58 |

| Legal environment score | 14 out of 30 |

| Political environment score | 21 out of 40 |

| Economic environment score | 12 out of 30 |

| Number of official languages | 37 |

| Number of indigenous languages with official status | 36 |

What You'll Learn

Bolivia's 2009 Constitution and free press

Bolivia's 2009 Constitution, also known as the Constitution of the Plurinational State of Bolivia, guarantees the right of Bolivians to freedom of expression, opinion, and information. This includes the freedom to express and disseminate thoughts and opinions by any means of oral, written, or visual communication, as well as the right to access and interpret information freely. The Constitution also guarantees the freedom of expression and the right to communication and information to workers of the press.

The Constitution recognises the conscience clause of information workers and states that public means of communication must respect the principles of truth and responsibility. It also prohibits the formation of monopolies or oligopolies in the media sector and encourages the creation of communitarian means of communication with equal conditions and opportunities.

Additionally, the 2009 Constitution defines Bolivia as a unitary plurinational and secular state, moving away from its previous identification as a Catholic state. It calls for a mixed economy of state, private, and communal ownership, restricts private land ownership, and recognises various autonomies at the local and departmental levels.

Overall, the 2009 Constitution of Bolivia provides a framework that supports freedom of expression and press freedom in the country. It ensures that individuals and the press have the right to express themselves freely and access information without censorship. However, it is important to note that the implementation and enforcement of these constitutional guarantees may vary in practice.

English Teachers in Bolivia: Employees or Contractors?

You may want to see also

The Morales administration and free press

Bolivia's 2009 constitution protects freedom of speech and the press, but it also allows for some limitations. While Article 21 lays out an expansive right to communicate freely, Article 107 imposes a duty to communicate with "truth and responsibility". This article also allows for content-based restrictions, requiring the media to promote the ethical, moral, and civic values of the nation's multiple cultures.

The Morales administration has been accused of using the 2010 Law against Racism and All Forms of Discrimination to intimidate and stifle the media. The law grants authorities the power to fine or shut down news outlets and arrest journalists for published material that is deemed to be racist. In August 2012, the Morales government used the law against the media for the first time, filing charges against three outlets: the news agency Fides (ANF) and the newspapers El Diario and Página Siete. The government alleged that they had distorted the president's words in a speech blaming hunger in eastern Bolivia on lazy people.

In March 2012, Rogelio Peláez of the monthly news journal Larga Vista was sentenced by a criminal court in La Paz to 30 months in prison for defaming a lawyer in a 2010 article. In October 2012, the Constitutional Tribunal struck down Article 162 of the penal code, which criminalized libel of public officials, though the scope and overall effect of the ruling remained unclear.

The Morales administration has continued to use legal, political, and economic means to place pressure on independent outlets. Media outlets are encouraged to avoid publishing any negative comments about the government, which has led to self-censorship.

In October 2010, Vice President Alvaro García Linera said he personally wrote down the names of individuals who insulted President Morales via social media. Interior Minister Carlos Romero said social media was being monitored and that those who insulted the president would face possible criminal charges. However, he also said that the proposed regulations wouldn't impact citizens' right to freely express their opinions.

In February 2012, almost 47% of journalists surveyed in a National Press Association (ANP) poll admitted to practicing some form of self-censorship.

Cartels in Bolivia: A Complex Web of Power and Influence

You may want to see also

Attacks, threats, censorship, and harassment by the government

During a period of political turmoil and instability, abuses against the press included intimidation, harassment, threats, physical assaults, theft of equipment, and radio and TV censorship. Journalists face verbal harassment and damage to their reputations, with stigmatisation becoming increasingly trivialised.

Journalists who are considered troublesome are regularly victims of judicial harassment. Under Supreme Decree 181, journalists who "lie", "play party politics", or "offend the government" may be deprived of government advertising. This, alongside arbitrary arrests and a high level of impunity, fosters a climate of self-censorship throughout the country. Many killings of journalists have gone unpunished.

The Bolivian government controls many newspapers and has increased its monitoring of critical media, especially on social media. The ownership of privately-owned media is highly concentrated, jeopardising pluralism. Self-censorship is a consequence of the ties between media owners and the government.

Media outlets linked to the government enjoy privileges, but independent media are exposed to strong economic pressure, including the threat of withdrawal of state advertising, which can lead to their closure. As a result, journalists face job insecurity.

Violence against journalists has become more common, with attacks coming from government supporters or politicians. Physical attacks against journalists have intensified since 2020, especially in rural areas. Many radio and TV stations have had their premises vandalised and have been forced to interrupt their activities.

Hummingbirds in Bolivia: A Natural Wonder

You may want to see also

Self-censorship in Bolivia

The Morales administration has been accused of using legal, political, and economic means to pressure independent outlets. This has led to self-censorship, with journalists avoiding publishing negative comments about the government. According to a 2016 article, 47% of journalists surveyed admitted to practicing some form of self-censorship.

The government's anti-racism law, which aims to protect indigenous communities from racist media portrayals, has also been criticised for its potential to censor or close media outlets. The law grants authorities the power to fine, shut down, or arrest journalists and media outlets for publishing racist content. While there have been no convictions under this law as of February 2014, it has been criticised as a dead letter by Bolivian media.

In addition, journalists in Bolivia face challenges such as low literacy rates, limited advertising, and a lack of access to official sources. These factors, along with the threat of legal ramifications and violence, contribute to a climate of self-censorship in the country.

Bolivian Ram Cichlids: Aggressive or Peaceful Tank Mates?

You may want to see also

The political and legal environment in Bolivia and free press

Bolivia is a landlocked country in central South America with a population of around 12 million. It is a unitary republic with a representative democratic government and a multi-ethnic population, including Amerindians, Mestizos, Europeans, Asians, and Africans. The country gained independence from Spain in the 19th century and has since been governed by a mix of military and civilian governments.

In terms of the political and legal environment, Bolivia has a multiparty democracy with an elected president and a bicameral legislature. The country's constitution, adopted in 2009, established four branches of government: legislative, executive, judicial, and electoral. The legislative branch, known as the Plurinational Legislative Assembly, is bicameral, with a House of Representatives and a Senate. The executive branch is headed by the president, who is currently Luis Arce of the Movement Towards Socialism party. The judiciary is independent but has been criticised for corruption and political influence.

Bolivia's political and legal environment has had an impact on the freedom of the press in the country. While the constitution protects freedom of speech and of the press, there are also some limitations. For example, the 2010 Law against Racism and All Forms of Discrimination has been used to intimidate and censor the media. Defamation also remains a criminal offence, and journalists have been sentenced to prison terms for allegedly defaming public figures.

The political environment in Bolivia can be polarised, with strong rivalries between pro- and anti-government media outlets. Government officials have been known to use negative rhetoric against the media and have even threatened critics of the president with criminal charges. This has led to self-censorship among journalists and media outlets, who fear retribution from the government.

In terms of legal restrictions, Bolivia's telecommunications law gives the government control over 33% of television and radio frequencies. Additionally, the country's electoral law restricts coverage of judicial elections, limiting the publication of information about candidates.

Overall, while Bolivia's constitution guarantees freedom of speech and of the press, the political and legal environment can pose challenges to these freedoms. Journalists and media outlets often face pressure, censorship, and even physical attacks.

Watch Peru vs Bolivia: Streaming Options for the Match

You may want to see also