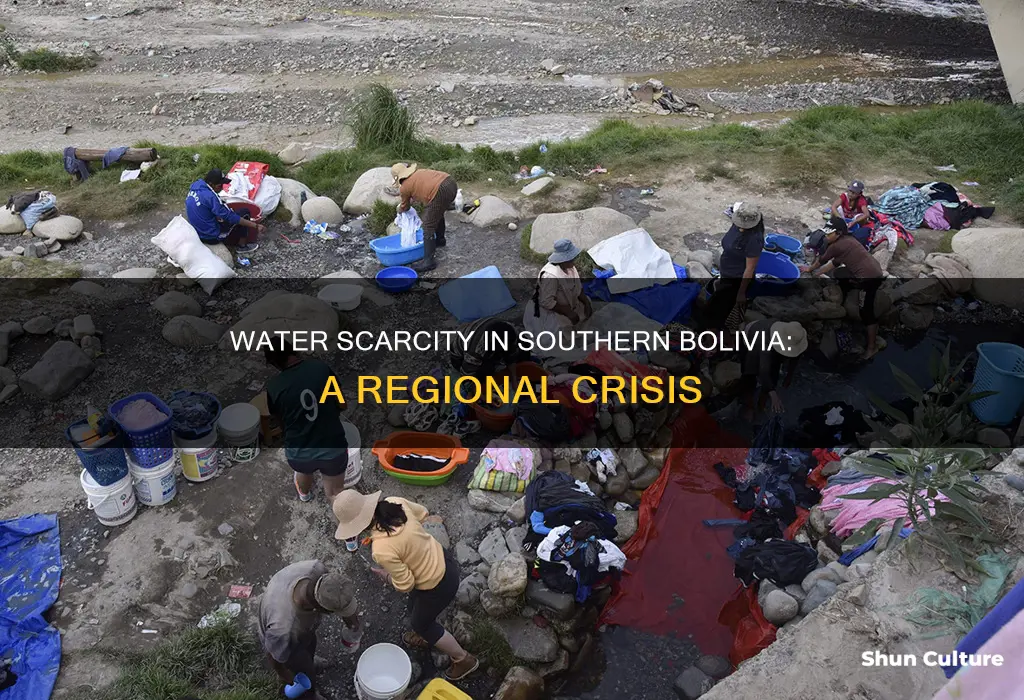

Water scarcity is a pressing issue in Southern Bolivia, with climate change, political instability, and privatisation contributing to the problem. Bolivia is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change, with rising temperatures, severe flooding, and long droughts impacting water availability. Political instability, such as protests against water privatisation and the election of Evo Morales, has also played a role in the water crisis. Additionally, privatisation efforts have led to conflicts over water resources and unequal access, with rural areas and indigenous communities disproportionately affected. The combination of these factors has made water scarcity a significant challenge in Southern Bolivia, requiring innovative solutions and increased investment in infrastructure.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Population | 11.05 million |

| Rural access to basic water services | 78% |

| Rural access to basic sanitation services | 36% |

| Percentage of people without water security | 30% |

| Percentage of people without access to adequate sanitation | 50% |

| Number of people who died in the Cochabamba Water War | 1 |

| Number of people injured in the Cochabamba Water War | 100+ |

| Year of the Cochabamba Water War | 2000 |

| Year Bolivia was hit by the most severe drought since the 80s | 2016 |

| Number of people left without a water supply in La Paz | 400,000 |

| Percentage of crops lost in some areas in the highlands | 90% |

| Average temperature increase in Bolivia by 2030 | 2 ºC |

| Average temperature increase in Bolivia by 2100 | 5-6 ºC |

What You'll Learn

The Cochabamba Water War

The Build-Up to the War

Prior to privatisation, Cochabamba's waterworks were controlled by the state agency SEMAPA. However, the system was inefficient, costly, and unable to meet the growing demand, especially amid increasing water scarcity. Facing economic collapse in 1985, Bolivia sought financial aid from the World Bank, which pushed for the privatisation of the country's railroads, airlines, telephone system, oil industry, and water. In compliance with the World Bank's requirements, Bolivia put SEMAPA up for auction.

Aguas del Tunari, a multinational water consortium, was the sole bidder for the privatisation of Cochabamba's water system. They were awarded a 40-year contract and the exclusive right to the city's water system, with an annual rate of return of over 15%. This deal was facilitated by the Bolivian government passing Law 2029, which legalised water privatisation and appeared to give Aguas del Tunari a monopoly over all water resources, including water used for irrigation by peasant farmers.

The Protests

In January, February, and April 2000, protests erupted in Cochabamba, largely organised through the Coordinadora (Coalition in Defense of Water and Life), a community coalition. The demonstrations were sparked by drastic increases in water rates implemented by Aguas del Tunari, which had raised rates by an average of 35% to about $20 a month—a significant sum for residents whose monthly income was often only about $100.

The protests culminated in tens of thousands of people marching downtown and clashing with police. One civilian was killed by a Bolivian Army captain who opened fire on a crowd of demonstrators. Dozens more were injured, and several protesters were arrested. The demonstrations spread beyond Cochabamba to other cities and rural areas, and the protesters' demands expanded to include calls for the government to address unemployment and other economic issues.

The Outcome

On April 10, 2000, the Bolivian government reached an agreement with the Coordinadora to reverse the privatisation. The agreement included the removal of Aguas del Tunari, the transfer of control of Cochabamba's water supply to the Coordinadora, the release of detained protesters, and the repeal of water privatisation legislation.

Bolivia's Tin Exports: A Global Trade Perspective

You may want to see also

Climate change

The effects of climate change in Bolivia are already evident. The country has experienced severe flooding in certain regions, caused by El Niño, alongside prolonged and intense droughts. In 2016, Bolivia was hit by its most severe drought since the 1980s, which affected several cities, including Oruro, Potosí, Cochabamba, Sucre, and La Paz. This drought had a significant impact on both urban and rural areas, leading to crop losses and a state of national emergency.

The impact of climate change on water resources in Bolivia is particularly concerning. Retreating tropical glaciers are reducing freshwater resources for highland communities and the urban populations of El Alto and La Paz, who rely on glacial melt as a major source of drinking water. Water levels in Lake Titicaca, which millions of people depend on, have reached their lowest levels since 1949.

Additionally, climate change-induced extreme weather events have exacerbated Bolivia's water challenges. Droughts have disrupted water systems and agricultural economies in rural communities, while torrential rains and floods have overwhelmed water and sanitation infrastructure in urban areas.

To address these challenges, the Bolivian government has recognised the need for significant investment in water and sanitation infrastructure. The national development plan includes a $700 million investment between 2010 and 2015 to upgrade infrastructure and adapt to climate change. However, the country still relies heavily on foreign investment to fund these initiatives.

While climate change is a critical factor in water scarcity, it is important to note that other factors, such as government policies, mining operations, and deforestation, also play a role in exacerbating water-related issues in southern Bolivia.

Bolivians March: Democracy, Rights, and a Call for Change

You may want to see also

Poor infrastructure

Water scarcity in Southern Bolivia is partly due to poor infrastructure. The country's water infrastructure is in need of significant investment to upgrade and expand existing systems and develop new water sources. This is due in part to the country's reliance on foreign investment and loans to fund these projects, which can introduce unpredictability and risk, especially in times of financial crisis.

The lack of investment in water infrastructure has led to issues such as leaks and clandestine hook-ups, with an estimated 35% of water being lost in these ways. The small, independent water providers that manage these systems are burdened with poorly constructed and deteriorated infrastructure, operating deficiencies, and community conflicts.

In addition, the decentralized nature of Bolivia's administrative structure means that water management responsibilities are shared between the Water Ministry and departmental and municipal governments, leading to overlapping jurisdictions and conflicts. The Water Ministry itself has also been plagued by frequent reorganizations and institutional instability, with critics arguing that it operates more like a loose federation of sub-ministries rather than a coherent organization.

The combination of poor infrastructure, bureaucratic issues, and lack of investment has contributed to water scarcity in Southern Bolivia, particularly in rural and peri-urban areas. These issues have also led to intermittent water service and high costs for consumers, with those outside the grid forced to pay 5 to 10 times more for trucked-in water of dubious quality.

The Hub of Bolivian Immigrants: Where is it?

You may want to see also

Political instability

The Water War was precipitated when SEMAPA was sold to a consortium controlled by the US-based company Bechtel, in exchange for debt relief for the Bolivian government and new World Bank loans to expand the water system. Bechtel was granted broad powers over water resources, including control of communal water systems in the countryside, which had never been hooked into the grid. This led to widespread fears that even rainwater collected by local farmer-irrigators would fall under Bechtel's control.

The privatisation also resulted in a 50% average increase in water rates for SEMAPA customers, further fuelling discontent. In response to the protests, the Bolivian government passed Law 2029, which appeared to give a monopoly over all water resources to the consortium, Aguas del Tunari. This included water used for irrigation by peasant farmers and independent communal water systems. Many Bolivians saw the implementation of Law 2029 as symbolic of the issues with the neoliberal development strategy, including its lack of concern for equity and its rejection of the role of the state.

The protests united a diverse range of groups, including farmers, factory workers, rural and urban water committees, neighbourhood organisations, students, and middle-class professionals. The demonstrations spread beyond Cochabamba to other areas, including La Paz, Oruro, and Potosí, as well as rural areas. The protesters' demands expanded to include calls for the government to address unemployment and other economic issues. The government responded by declaring a state of siege, suspending constitutional guarantees, and restricting travel, political activity, and freedom of the press.

The Water War ultimately led to the reversal of privatisation, with the national government reaching an agreement to revoke the privatisation law and return water supply to public hands. This event had a significant impact on the political landscape in Bolivia, contributing to the election of Evo Morales and the rise of the MAS (Movement Towards Socialism) party. It also inspired a worldwide anti-globalisation movement and provided a model for water-justice struggles worldwide.

However, despite these gains, Bolivia continues to face significant challenges in ensuring access to water and sanitation services for its population. The Water Ministry, created in 2006 to manage water supply, sanitation, and environmental protection, has been plagued by frequent reorganisations and institutional instability, with six changes in leadership since its creation. The country remains highly dependent on foreign investment to address its water infrastructure needs, and critics argue that the government's budget priorities reflect a continued commitment to a "neo-extractivist" development model.

In conclusion, political instability in Bolivia has been influenced by the country's struggle to secure access to water, particularly in the context of privatisation and the subsequent efforts to establish alternative models. The Cochabamba Water War was a pivotal event that shaped the country's political landscape and contributed to broader movements for social justice and anti-globalisation. However, ongoing challenges in water management and infrastructure development continue to impact the country's political stability.

Hiring in Bolivia: What Businesses Need to Know

You may want to see also

Foreign investment

Bolivia is generally open to foreign direct investment (FDI), although there are no significant incentives to encourage it. The country's 2014 Investment Law guarantees equal treatment for national and foreign firms, but public investment takes priority. Bolivia's constitution also states that Bolivian investment takes priority over foreign investment.

In 2021, gross FDI flows to Bolivia reached USD 440 million, with the leading sectors being hydrocarbons, manufacturing, industry, and commerce. However, there is no significant FDI from the United States, and Bolivia has abrogated its Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) with the US in 2012. Bolivia's current macroeconomic stability, abundant natural resources, and strategic location make it a prospective country for investment.

The country's investment climate is affected by a lack of legal security, corruption allegations, and unclear investment incentives. The judicial system is also believed to be compromised and politicized, making it challenging for investors to seek recourse for disputes.

Bolivia's economy is state-run, focusing on public spending. The government owns and operates over 60 businesses in sectors it considers strategic, including energy, mining, telecommunications, and banking. However, many state-owned enterprises are inefficiently managed, and the economy is fragile and vulnerable to external shocks.

Foreign and domestic private entities have the right to establish and own businesses in Bolivia. However, foreign investment is restricted in certain sectors, such as natural resources and broadcast licenses. Additionally, there is a "border security zone" within 50 kilometers of the border where foreign entities cannot acquire property.

Bolivia has a right-wing populist government, which has nationalized companies in "strategic" sectors, including extractive industries, telecommunications, and electricity. This has further contributed to the uncertain investment climate, especially for foreign investors.

The country has a complicated regulatory system, with cumbersome bureaucratic procedures that impede investment. The process of registering a new business can take around 30 days, and there is no simplified process for business creation.

Despite the challenges, Bolivia offers investment opportunities in various sectors, including agriculture, energy, critical minerals, and mining.

Bolivia's Border Status: Open or Closed?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Water scarcity is not unique to Southern Bolivia, but the entire country is facing severe water shortages. Bolivia is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change, with rising temperatures, severe flooding, and long droughts affecting its water systems.

The main causes of water scarcity in Southern Bolivia include:

- Climate change: Rising temperatures, severe flooding, and long droughts are reducing water availability.

- Deforestation and environmental degradation: Bolivia's environmental vulnerability is partly due to the existence of diverse ecosystems and increasing deforestation.

- Population growth and urbanization: The growing population in Southern Bolivia increases demand for water, and urbanization puts pressure on water resources.

- Inefficient water management: There is a lack of investment in piped water systems and water infrastructure, and the water ministry faces institutional instability and overlapping jurisdictions with other cabinet ministries.

The impacts of water scarcity in Southern Bolivia include:

- Health risks: Lack of access to clean water and sanitation services can lead to waterborne diseases and other health issues.

- Economic impacts: Water scarcity can affect agricultural productivity and impact industries such as mining and hydropower generation, which rely on water.

- Social and political unrest: Water scarcity can lead to social and political tensions, as seen in the Cochabamba Water War, where protests against water privatization turned violent.