The Afro-Bolivian community is made up of Bolivians of Sub-Saharan African heritage, descended from slaves brought to the country by Spanish colonizers during the 16th and 19th centuries. The Afro-Bolivian population is estimated to be between 23,000 and 25,000 people, with the majority living in the Yungas region of the Department of La Paz.

Historically, Afro-Bolivians have faced discrimination and racism, with many living in rural and semi-urban areas. Despite these challenges, the community has preserved its culture, including music, dance, and language. The election of Evo Morales as Bolivia's first indigenous president in 2005 was welcomed by many Afro-Bolivians, as he vowed to improve the living standards of socially excluded groups.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Population | 23,300 (2012 census); 25,000 estimated |

| Location | Yungas region of the Department of La Paz |

| Occupation | Farmers |

| Language | Bilingual in Aymara and Spanish |

| Religion | Roman Catholic Andean syncretism |

| Self-description | 'Afro-Bolivian' adopted in the 1990s |

| History | Descended from slaves brought to work in the silver mines in Potosí in the early 1500s |

| Monarchy | Ceremonial monarchy recognised in 2007, led by King Julio Pinedo |

| Culture | Saya music and dance, traditional clothing |

| Representation | Excluded from the 2001 census; recognised as a minority ethnic group in the 2009 Constitution |

What You'll Learn

- Afro-Bolivians are one of the 36 recognised ethnic groups in Bolivia

- Afro-Bolivians are descended from slaves brought to Bolivia by the Spanish in the 16th century

- Afro-Bolivians are led ceremonially by a king, Julio Pinedo, who traces his lineage to African royalty

- Afro-Bolivians have been discriminated against and face racism in Bolivia

- Afro-Bolivian women face intersectional discrimination, where racism and sexism converge

Afro-Bolivians are one of the 36 recognised ethnic groups in Bolivia

After their emancipation in 1827, Afro-Bolivians relocated to the Yungas, a place where most of the country's coca is grown. It is estimated that 25,000 Afro-Bolivians live in the Yungas today. They are proud of their culture and have fought to preserve it. However, many have also reported experiencing severe racism and feelings of isolation from society due to intolerance.

Afro-Bolivians are ceremonially led by a king, who traces his descent back to a line of monarchs that reigned in Africa during the medieval period. The current king, Julio Pinedo, is a direct descendant of Uchicho, a prince from the ancient Kingdom of Kongo, who was brought to Bolivia as a slave.

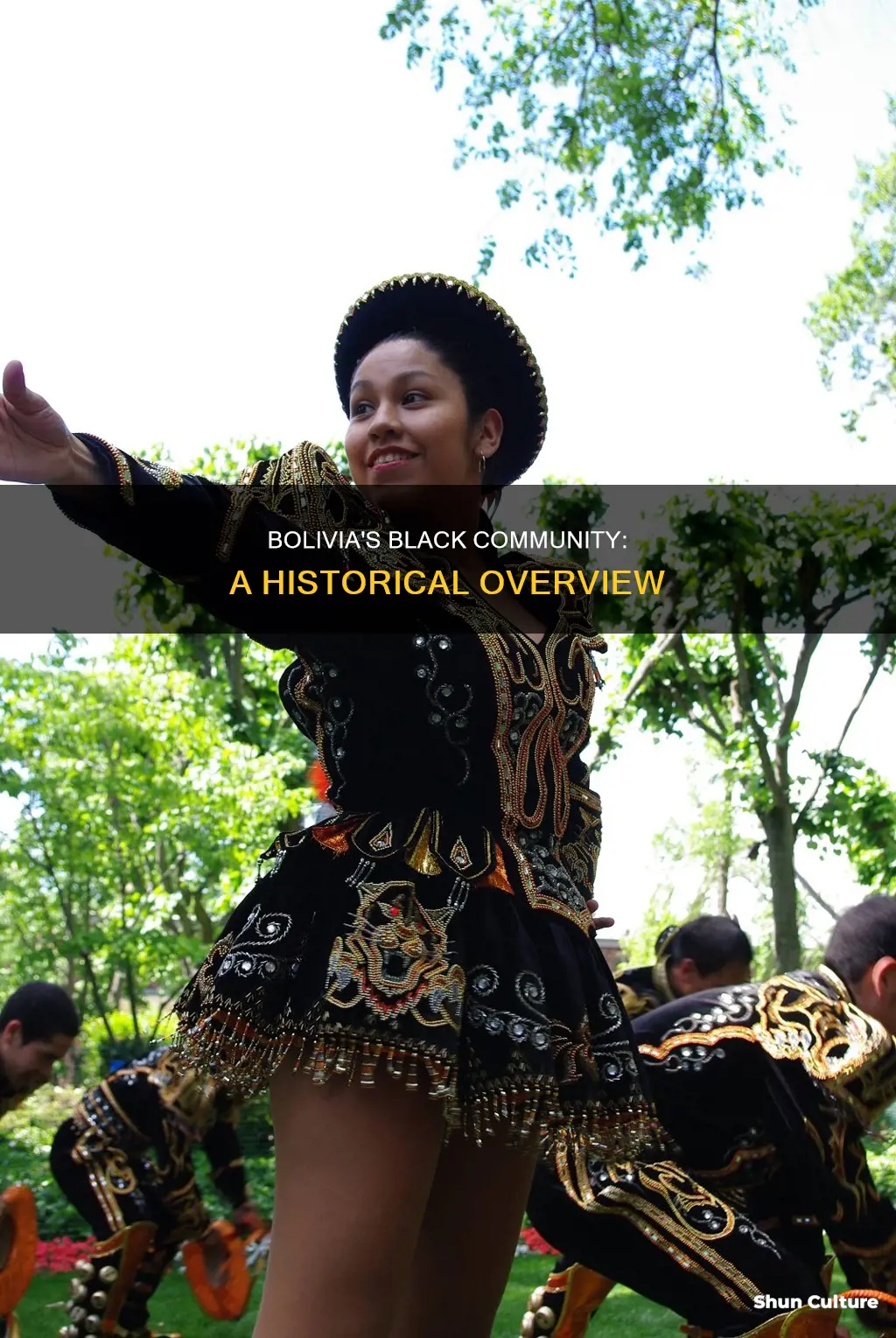

Afro-Bolivians have traditionally maintained their own creole language, with links to earlier Bozal Spanish. They also have their own distinctive music and dance, such as Saya music or La Saya, which involves Andean instruments incorporated with African percussion.

In 2009, President Evo Morales added amendments to the national constitution that outlined the rights of Afro-Bolivians and guaranteed the protection of their liberties. The amendments also generally extended to indigenous peoples and officially recognised Afro-Bolivians as a minority group in Bolivia.

Mountain Biking in Bolivia: Is It Possible?

You may want to see also

Afro-Bolivians are descended from slaves brought to Bolivia by the Spanish in the 16th century

The slaves brought to Bolivia by the Spanish faced inhumane conditions. They were forced to work 12-hour shifts in the mines, enduring low temperatures, toxic gases, and asbestos. The altitude, approximately 4,000 meters above sea level, also took a toll on their health. It is estimated that as many as eight million Africans and natives died from working in the mines between 1545 and 1825.

In addition to mining, the Spanish also imported African slaves to work on coca-leaf plantations in the provinces of the Yungas, located north of La Paz. Here, they faced similar exploitation and harsh conditions. The Afro-Bolivian community has historically suffered from discrimination, racism, and invisibility within Bolivian society, with many living in rural and semi-urban areas. Despite these challenges, the Afro-Bolivian community has fought to preserve its culture and increase its recognition within the national territory.

Afro-Bolivians have made significant contributions to Bolivian culture, particularly in the form of music and dance. Saya, or La Saya, is a traditional dance that originated from Sub-Saharan Africa and has become a popular form of expression for the Afro-Bolivian community. The dance involves Andean instruments incorporated with African percussion, such as drums, gourds, shakers, and jingle bells attached to the dancers' clothing. The revival of the saya dance in the late 20th century became a pivotal part of the black consciousness movement in Bolivia.

Today, there are approximately 25,000 Afro-Bolivians living in the country, with the largest concentrations found in the lowland provinces of Nor Yungas and Sud Yungas in the department of La Paz. While they have faced severe racism and feelings of isolation, there have been efforts to improve their inclusion and recognition. In 2009, President Evo Morales added amendments to the national constitution that outlined the rights of Afro-Bolivians and guaranteed their protection.

Death Road, Bolivia: Worth the Risk?

You may want to see also

Afro-Bolivians are led ceremonially by a king, Julio Pinedo, who traces his lineage to African royalty

The Afro-Bolivian community is ceremonially led by King Julio Pinedo, who has been the symbolic monarch of Afro-Bolivians since 1992. The Royal House was officially recognized by the Bolivian state in 2007 with the coronation of Julio, the current King of the Afro-Bolivian community.

The Afro-Bolivian Royal House is a ceremonial monarchy recognized as part of the Plurinational State of Bolivia, which does not interfere with the system of the Presidential republic in force within the country. The monarchy is centred in Mururata, a village in the Yungas region of Bolivia, and is treated as a customary leader of the Afro-Bolivian community. The powers of the king are similar to those of a traditional monarch, representing the Afro-Bolivian community.

King Julio traces his lineage to African royalty. His ancestor was Prince Uchicho of the Kongo people, who was brought to Bolivia around 1820 as a slave. Other slaves recognized Uchicho as a man of regal background—a prince from the ancient Kingdom of Kongo—when they saw his torso exposed with royal tribal marks. Uchicho was crowned in 1823 and was succeeded by Bonifaz, who adopted the surname Pinedo, followed by Don José and Don Bonifacio. When Bonifacio died in 1954, the house was led by his oldest daughter, Doña Aurora Pinedo, until Julio, her oldest son, was given the title of king in 1992.

The Afro-Bolivian community in Bolivia dates back to the colonial era when Africans were imported as slaves to labour in the silver mines of the Peruvian viceroyalty. Africans were also imported as slave labour to work on coca-leaf plantations in the semitropical provinces of Nor Yungas and Sud Yungas. Emancipation was legislated in Bolivia's constitution of 1827, but its enforcement was delayed until 1851.

Afro-Bolivians have a strong sense of being "negros" (their preferred term) and possess cultural and linguistic values that set them apart from their compatriots. They have traditionally maintained their own creole language, with links to earlier Bozal Spanish. They are usually distinguished from 'whites' and mestizos in economic rather than racial terms, and most tend to think of themselves as Bolivian rather than African. However, many Afro-Bolivians have reported experiencing severe racism and feelings of isolation from society due to intolerance.

The biggest African influence in Bolivian culture is Saya music or La Saya, which involves Andean instruments incorporated with African percussion. The primary instrument is the drum, passed on by their African ancestors, along with gourds, shakers, and even jingles bells that are attached to their clothing at the ankle.

Visa for Bolivia: Getting It in Cusco

You may want to see also

Afro-Bolivians have been discriminated against and face racism in Bolivia

Afro-Bolivians have a long history of facing discrimination and racism in Bolivia. The problems began with their very arrival in the country, as they were brought over as slaves from Sub-Saharan Africa in the early 1500s to work in the silver mines in Potosí. Many died due to maltreatment, inhumane conditions, and the cold temperatures at high altitudes.

Even after emancipation in 1827, Afro-Bolivians continued to face severe racism and discrimination. They were excluded from Bolivia's official census for over a century, despite repeated demands to be included. They have also long faced disadvantages in health, life expectancy, education, income, literacy, and employment.

Afro-Bolivians in rural areas experience the same types of problems and discrimination as Indigenous people who live in those areas. Afro-Bolivian community leaders have reported that employment discrimination is common and that public officials, particularly the police, discriminate in the provision of services. They also report the widespread use of discriminatory language.

Racism and racial disparities persist in Bolivia, and Afro-Bolivian women, in particular, experience intersectional discrimination where racism and sexism converge, worsening their living conditions. Despite the political constitution institutionally recognizing their presence in the national political space, there has been no significant progress in the participation of Afro-Bolivians in decision-making.

Afro-Bolivians have also been underrepresented in the media. They were not included in the 2001 census and were only recognized as a distinct ethnic/cultural group in the 2012 census. This lack of recognition has contributed to the perpetuation of stereotyped images and the reduction of Afro-Bolivians to their cultural contributions, such as saya music.

Despite these challenges, Afro-Bolivians have fought to preserve their culture and traditions. They have made some progress in recent years, with the election of Evo Morales in 2005, who recognized and named Afro-Bolivians as a specific minority ethnic group in the 2009 Constitution. However, racism remains a persistent issue in Bolivia, and Afro-Bolivians continue to face discrimination and inequality in various aspects of their lives.

Finishing Bolivian Rosewood: Techniques for a Smooth Finish

You may want to see also

Afro-Bolivian women face intersectional discrimination, where racism and sexism converge

Historically, the Afro-Bolivian community has been subjected to discrimination, racism, and invisibility within national society. This is partly due to their concentration in rural and semi-urban areas, leading to claims that there are no black people in Bolivia. In response, Afro-Bolivian leaders have mobilized to increase recognition of their culture and presence in the country. While the democratic nature of the plurinational state now formally recognizes indigenous and Afro-Bolivian populations, the representation of Afro-Bolivians is often limited to stereotypical images and cultural elements such as saya music.

Afro-Bolivian women have played a pivotal role in the survival of their people and the leadership of their organizations. However, their specific demands as Black women are often overlooked within the broader Afro-Bolivian movement. The discrimination they face is not merely a layering of racism and sexism but a convergence of factors that intensify each other. This intersectional discrimination is further exacerbated by the poverty experienced by Afro-descendant women in Latin America, which results in limited access to education, precarious employment, and inadequate health services.

The situation of Afro-Bolivian women reflects broader issues of gender inequality in Bolivia. Despite constitutional guarantees of equal rights, women in Bolivia continue to face discrimination and struggle in various aspects of their lives. They often bear the almost exclusive responsibility for domestic work, and Bolivia has the highest prevalence of domestic violence against women among twelve Latin American countries studied by the Pan American Health Organization. Additionally, Bolivian women are exposed to excessive machismo and are frequently utilized as promotional tools in advertising, perpetuating stereotypes and assumptions.

The intersection of gender and ethnicity creates a unique set of challenges for Afro-Bolivian women. While access to education has improved in Bolivia, significant gender gaps persist among indigenous and rural students. In urban areas, indigenous female students are half as likely to finish secondary school compared to their non-indigenous male counterparts. The barriers are even more pronounced for Afro-Bolivian women, who face discrimination in academic environments and limited access to key health services.

Bolivia's Constitution: Term Limits and Their Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

According to the 2012 census, there are 23,000 Afro-Bolivians, although estimates range from 6,000 to 158,000.

Most Afro-Bolivians live in the Yungas region of the Department of La Paz, in villages such as Chicaloma, Chulumani, Mururata, and Tocaña.

Afro-Bolivians are the descendants of enslaved West Africans, brought by the Spanish between the 16th and 19th centuries to work in the mines of Potosí.