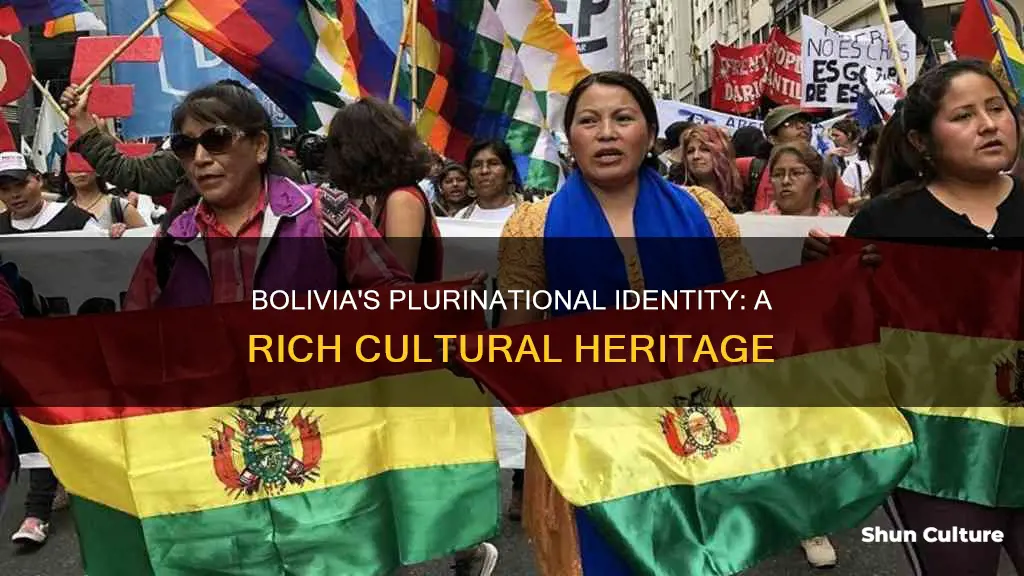

Bolivia is officially known as the Plurinational State of Bolivia, a title that reflects the country's recognition of multiple political communities and nationalities within its borders. The concept of plurinationalism, which first emerged in the early 1980s, is defined as the coexistence of two or more distinct national groups within a single polity. In the context of Bolivia, a plurinational state acknowledges the presence of diverse indigenous groups, each with their own unique cultures, languages, and worldviews. The adoption of plurinationalism in Bolivia's 2009 Constitution was a significant step towards recognising the rights and representation of indigenous peoples, who constitute the majority of the country's population.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition of plurinationalism | The coexistence of two or more sealed or preserved national groups within a polity |

| Definition of a plurinational state | The existence of multiple political communities and constitutional asymmetry |

| Origin of the term | Indigenous political movement in Bolivia in the early 1980s |

| Plurinational states | Bolivia and Ecuador |

| Plurinational democracy | Recognizes the multiple demoi within a polity |

| Multinational states | Similar to plurinational states but are often advocated for by indigenous peoples |

| Constitutional plurinationalism in Chile | Topic of debate; proposed in the 2022 Political Constitution of the Republic of Chile but was rejected |

| Plurinational region in Chile | Proposed by scholars and activists as a solution to the Mapuche conflict |

| Criticism of plurinationalism | Used to advance Bolivian claims against Chile for sovereign access to the Pacific Ocean |

| Bolivia's adoption of plurinationalism | Seen as a way to institutionalize the revolutionary struggle against colonialism and inequality |

| Limitations of plurinationalism | May not fully address the oppression faced by indigenous communities and could maintain the status quo |

| Examples of plurinationalism in the 2009 Bolivian Constitution | Official status of indigenous languages, symbols, and moral principles; recognition of indigenous communities in legislative elections and judicial jurisdiction |

| Impact of plurinationalism in Bolivia | Granting autonomy to the state's departments, regions, indigenous communities, and municipalities |

What You'll Learn

Bolivia's 2009 Constitution

Bolivia is officially known as the Plurinational State of Bolivia, as reflected in its 2009 Constitution. This unique designation reflects the country's commitment to plurality and political, economic, legal, cultural, and linguistic pluralism. The concept of plurinationalism, which recognises the existence of multiple nationalities within a single state, is a defining feature of Bolivia's political and social organisation.

The 2009 Bolivian Constitution was the culmination of a process initiated by the 2006-2007 Constituent Assembly, envisioned by then-President Evo Morales. The Assembly sought to address the failures of multicultural policies in the preceding decades, which had led to discontent among the indigenous majority and corruption by international institutions and non-governmental organisations. The Constitution was approved by a referendum on 25 January 2009, with the people of Bolivia exercising their original power to manifest their commitment to the country's unity and integrity.

The preamble of the 2009 Constitution is replete with socialist, indigenist, and anti-colonial messages, signalling a break with the country's colonial, republican, and neoliberal past. It recognises the pre-colonial existence and ancestral domains of indigenous nations and peoples, guaranteeing their self-determination within the framework of a unified state. This includes the right to autonomy, self-government, cultural preservation, and the recognition of their institutions. The Constitution also establishes the official languages of the State as Spanish and all the languages of the rural native indigenous nations and peoples.

The plurinational state model, as outlined in the 2009 Constitution, represents a renegotiation of the relationship between law, culture, and ethnic identity within Bolivian society. It seeks to mobilise traditionally marginalised sectors, particularly peasants and indigenous populations, and promote their meaningful participation in political and social life. The Constitution also affirms social and economic rights, including the right to individual or collective property and inheritance. Additionally, it mandates the state to ensure the development of science and scientific research, allocating the necessary resources for the benefit of the public.

While the adoption of plurinationalism in Bolivia has been praised for its reformist and anti-imperialist intentions, it has also faced criticism. Some opponents, including indigenous leaders, argue that plurinationalism dilutes sovereign aims and maintains an unjust status quo. They claim that by conceding to the demands of non-indigenous groups, the Constituent Assembly inadvertently reinforced racially exclusionary neoliberal and colonial forms of citizenship and economic organisation. Despite these limitations, Bolivia remains the only state to fully embrace the concept of plurinationalism, showcasing its commitment to a revolutionary political project that recognises the diversity of its people.

Human Rights in Bolivia: Issues and Challenges

You may want to see also

Plurinationalism's critics

Plurinationalism in Bolivia has faced criticism from various quarters, including some indigenous leaders who argue that it falls short of achieving its stated aims of uprooting the oppression faced by indigenous communities and maintaining the unjust status quo.

Some critics, like the Aymara nationalist Felipe Quispe, have gone as far as to label the government of former President Evo Morales, an indigenous leftist, as "neoliberalism with an Indian face." They argue that plurinationalism maintains the status quo, where indigenous peoples remain separate from and inferior to the white-mestizo elite. Quispe and his supporters from the Pachakuti Indigenous Movement (MIP) and Unified Syndical Confederation of Rural Workers of Bolivia (CSUTCB) believe that full ethnic and economic liberation can only be achieved through self-determination and full sovereignty in the form of independent Quechua and Aymara states.

The 2011 TIPNIS protests, led by Bolivia's two largest indigenous movements, the Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia (CIDOB) and the National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu (CONAMAQ), further highlighted the limitations of plurinationalism. The protests were sparked by plans to construct a highway through the Isiboro Secure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS), which indigenous communities feared would lead to environmental destruction and a violation of their autonomy. Despite Morales' claims that the highway was necessary for the social and economic development of indigenous communities, his government's response to the protests caused indigenous leaders to question his commitment to their cause.

In addition to criticism from indigenous communities, plurinationalism has also faced opposition from elite conservative groups, who view it as a threat to the traditional unitary nation-state model. Furthermore, plurinationalism has been criticized by José Rodríguez Elizondo as being used to advance Bolivian claims against Chile for sovereign access to the Pacific Ocean.

Overall, while plurinationalism in Bolivia has been hailed by some as a revolutionary step towards recognizing and including indigenous peoples and cultures, it has also faced scrutiny and criticism from various groups, including those it was intended to benefit.

Exploring Coroico, Bolivia: Adventure, Nature, and Relaxation

You may want to see also

Indigenous opposition

Despite the Bolivian government's adoption of plurinationalism, some indigenous communities remain critical of this approach. They argue that it does not go far enough to address the historical oppression and ongoing marginalization of indigenous peoples in the country. This opposition is rooted in the belief that plurinationalism maintains the status quo, where indigenous peoples are separate from and inferior to the white-mestizo elite.

One of the most outspoken critics of plurinationalism from indigenous communities is Felipe Quispe, an ardent Aymara nationalist. He characterized the government of Evo Morales, Bolivia's first indigenous president, as "neoliberalism with an Indian face," suggesting that it merely paid lip service to indigenous rights without substantively challenging the power structures that perpetuate inequality.

The 2011 TIPNIS protests serve as a notable example of indigenous opposition to plurinationalism in Bolivia. In this instance, the Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia (CIDOB) and the National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu (CONAMAQ) protested the construction of a highway that would run through the Isiboro Secure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS). The organizations expressed concerns about potential environmental destruction and a violation of their autonomy. The Morales government's response to these protests, which included violent repression, caused indigenous leaders to question his commitment to their cause.

The TIPNIS protests highlighted a contradiction between Morales' ambitious development goals and his environmentalist and indigenist progressivism. Critics argue that this incident demonstrated the limitations of plurinationalism in achieving its stated aims of upending the legacy of colonialism and addressing long-standing inequality in Bolivia.

Furthermore, the 2019 overthrow of Morales' government can also be interpreted as a failure of plurinationalism. While the concept seeks to recognize the existence of multiple political communities and constitutional asymmetry, the persistent discontent among indigenous groups suggests that plurinationalism has not fully addressed their aspirations for self-determination and liberation from oppressive power structures.

The Bolivian context underscores the complexities of implementing plurinationalism and the ongoing struggle to reconcile the interests of diverse communities within a single nation-state. While plurinationalism offers an alternative model of state and citizenship, its effectiveness in challenging power structures and promoting meaningful change for indigenous peoples remains a subject of debate and ongoing evaluation.

Population Policies in Bolivia: What Are the Current Strategies?

You may want to see also

The 2011 TIPNIS protests

The protests were organised by the subcentral TIPNIS, the Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia (CIDOB), and the highland indigenous confederation CONAMAQ, with support from other indigenous and environmental groups. The march began on 15 August 2011 in Trinidad, Beni, and aimed to reach the national capital of La Paz.

The highway project was supported by domestic migrants, highland indigenous groups affiliated with peasant organisations, and the government. The project was part of President Evo Morales' infrastructure plan, funded by Brazil to access the Pacific Ocean. It would connect the agricultural region of Beni with the commercial crossroad of Cochabamba, reducing travel time by half. However, it would also cut through ancestral lands, leading to fears of an "invasion" of migrants and land grabs by loggers and cocaleros.

The protests turned violent, with a crackdown on 24 September resulting in four deaths. This led to the resignation of Defence Minister María Chacón Rendón and Interior Minister Sacha Llorenty. On 28 September, several thousand people gathered in La Paz to protest against the government crackdown and defend the national park, with a general strike called by the Central Obrera Boliviana affecting schools and medical services.

On 19 October, almost 2,000 protesters reached La Paz, despite the suspension of the project. They continued to call for the project's cancellation and the resignation of President Morales. Morales initially called the marchers "enemies of the nation" and sought to discredit them, but later apologised and called the protests a "wake-up call."

Asylum in the USA: A Guide for Bolivians

You may want to see also

Plurinationalism's future

The future of plurinationalism looked uncertain following the exile of former president Evo Morales in 2019. However, despite criticism from indigenous groups, Morales' ally Luis Arce and the MAS party regained power in 2020. It is possible that Bolivia's indigenous majority found the controversial plurinational approach, despite its imperfections, more acceptable than the right-wing alternatives offered by other political front-runners.

The application of plurinationalism in Bolivia has been influenced by the country's unique historical and cultural context, including its history as the center of the ancient Tiwanaku (Tiahuanaco) empire and its role in the Inca empire. Bolivia's mountainous western region, which is one of the highest inhabited areas in the world, is an important economic and political center. The country's diverse geographical regions, including the Andes Mountains, the Amazon River basin, and the Oriente region, are home to a variety of indigenous groups with pre-colonial ties to Bolivian territory.

The concept of plurinationalism in Bolivia is closely tied to the country's leftist indigenous political movement and its struggle against the legacy of colonialism and long-standing inequality. Proponents of plurinationalism see it as a way to recognize the existence of multiple ethno-cultural groups within the structure of a single nation-state and to mobilize traditionally marginalized social sectors, such as peasants and indigenous populations. However, opponents argue that plurinationalism dilutes sovereign aims and maintains the unjust status quo, failing to uproot the oppression faced by indigenous communities throughout Bolivian history.

Looking ahead, the future of plurinationalism in Bolivia depends on several factors, including the continued support of the MAS party and the ability of the government to address the concerns of indigenous communities. The success or failure of plurinational policies in Bolivia may also influence other countries facing similar challenges, such as Chile, Argentina, and Australia, which are exploring different ways to address the rights and representation of indigenous peoples.

Moving to Bolivia: Police Record Implications

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Plurinationality, plurinational, or plurinationalism is defined as the coexistence of two or more sealed or preserved national groups within a polity (an organized community or body of people).

Bolivia is called plurinational because it recognises the existence of various indigenous groups with pre-colonial ties to Bolivian territory and also codifies their cultural customs and practices within Bolivian law.

The term plurinational reportedly originated in the Indigenous political movement in Bolivia in the early 1980s.

Plurinationalism has faced scrutiny from some indigenous communities, who argue that it is too weak to uproot the oppression faced by indigenous communities throughout Bolivian history and that it maintains the status quo.