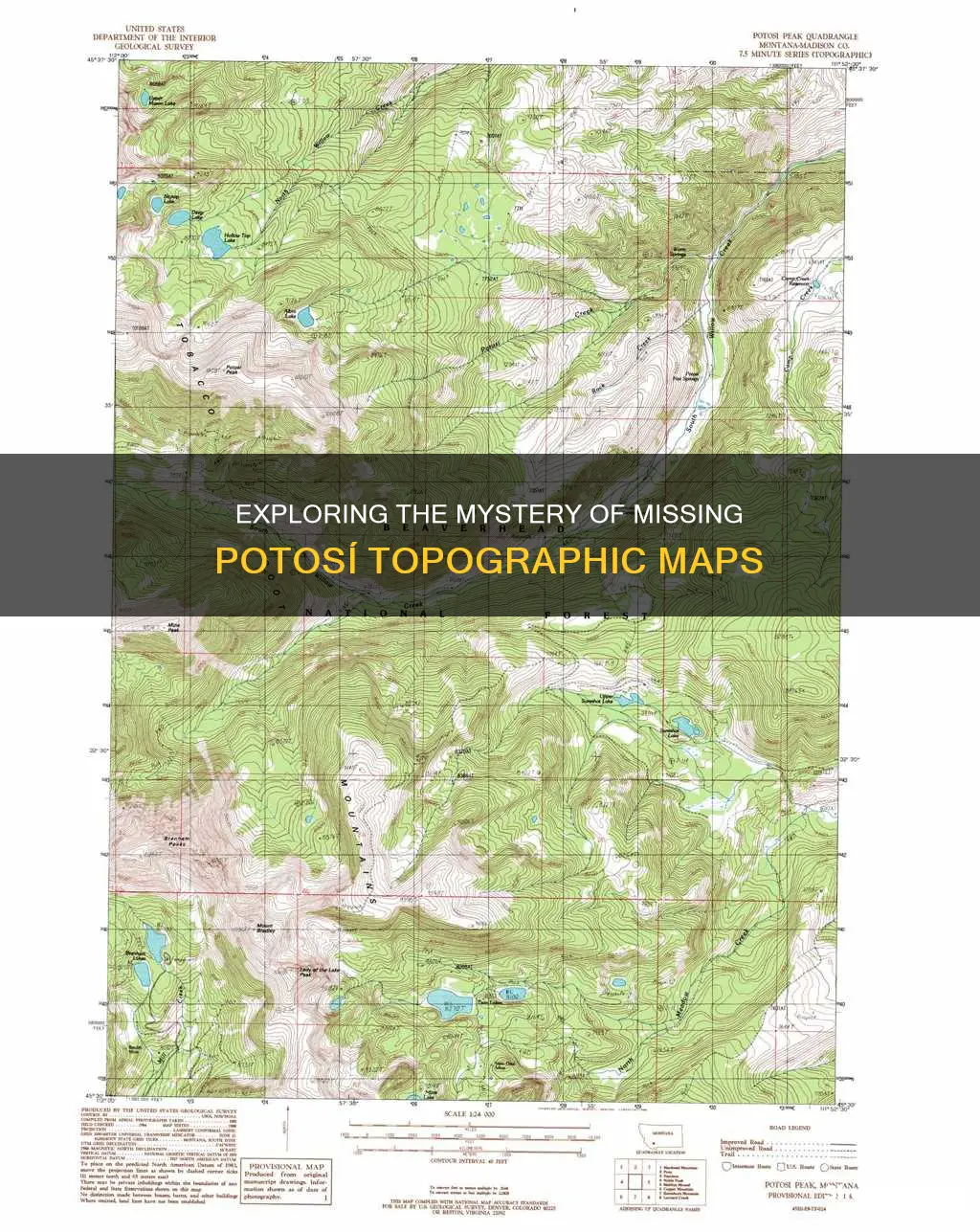

Potosí, Bolivia, is a city with a rich history of silver mining, which has earned it a place on the UNESCO World Heritage List. It is one of the highest cities in the world, with an elevation of 4,090 m (13,420 ft). With such a high altitude, it is no surprise that the city experiences a rare cold highland climate, with a long dry period and a short but strong wet season. The city is also known for its well-preserved colonial architecture. However, despite its fame and historical significance, there seems to be a lack of topographic maps of Potosí. This could be due to various reasons, such as the challenging terrain, the focus on other types of maps or data collection, or even political and bureaucratic factors. Nevertheless, the absence of topographic maps of Potosí, Bolivia, remains a gap that may be addressed in the future through dedicated surveying and mapping efforts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reason for no topographic maps | No clear reason found |

| Location | Bolivia, South America |

| Elevation | 3888m / 12756ft |

| Longitude | -65.755006 |

| Latitude | -19.572280 |

| Status | Capital city of the Potosí Department in Bolivia |

| Population | 154,700 (2010) |

| Climate | Semi-arid with average temperatures in its warmest month at 10 °C |

| Historical Importance | Major supply of silver for the Spanish Empire |

| UNESCO Status | Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site |

What You'll Learn

The Cerro Rico de Potosí mines

In recognition of its historical and ongoing importance, Potosí was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, along with the globally important Cerro Rico de Potosí mines. However, the site was added to UNESCO's list of endangered sites in 2014 due to "uncontrolled mining operations" that risk "degrading the site".

Bolivia's Seasons: A Year-Round Travel Guide

You may want to see also

The dangers of mining

Mining in Potosí is considered extremely dangerous, with the industry claiming the lives of hundreds of men every year. The Cerro Rico mine, in particular, is deemed the world's most dangerous mine. The mine has been in operation since the 16th century and has been subjected to centuries of mining, leaving the mountain porous and unstable.

The working conditions in the mines are harsh and dangerous. Miners work in close quarters with steep, narrow shafts that are lit only by candles. They are tasked with carrying heavy loads of ore up rickety ladders, often weighing between 100 and 300 lbs. As a result, accidents and injuries are common, and many workers have lost their lives due to falls or collapsing tunnels.

The high altitude of the mines also poses significant health risks. Workers are susceptible to pneumonia and other respiratory issues due to the extreme and rapid changes in temperature as they move between the hot depths of the mine and the freezing elements on the surface. Mercury poisoning is another serious concern, as it has claimed the lives of many involved in the refining process.

The use of dynamite in the mines further increases the risk of accidents and explosions. Miners often lack proper safety equipment, and the dust and silicon in the air pose long-term health hazards. The life expectancy of a miner is estimated to be around 50 years, with many falling victim to the hazardous working conditions and the toxic environment.

The Cerro Rico mine has a dark history of exploitation, dating back to the colonial era when Spanish colonisers forced indigenous labourers and African slaves to work in brutal conditions. Even today, miners work independently, selling their products at cheap prices to companies, who then supply products globally. Despite the dangers and low wages, mining remains a common occupation in Potosí, as it provides an opportunity for men to support their families and earn more than they would in other local industries.

Discovering Bolivia, Missouri: A Midwest Gem's Location

You may want to see also

The wealth of Potosí

Potosí was founded in 1545 as a mining town and soon produced fabulous wealth. The Cerro Rico produced an estimated 60% of all silver mined in the world during the second half of the 16th century. The city gave rise to a Spanish expression, still in use: "valer un Potosí" ("to be worth a Potosí"), meaning "to be of great value". The silver ore was extracted through a series of hydraulic mills and transported by llama and mule train to the Pacific coast, then shipped north to Panama City. From there, it was carried by mule train across the isthmus of Panama to Nombre de Dios or Portobelo, before being sent to Spain on the Spanish treasure fleets. Some silver was also transported to Acapulco, Mexico, and then sent via the Manila Galleons to buy Asian products.

In the 16th century, Potosí was considered the world's largest industrial complex. The city and its region prospered enormously, and it became directly associated with the massive import of precious metals to Seville, resulting in globally significant economic changes. The whole industrial production chain from the mines to the Royal Mint has been conserved, including the dams, aqueducts, milling centres, and kilns. The social context is equally well represented, with the Spanish zone and the very poor native zone separated by an artificial river.

Potosí's wealth also led to its growth as an administrative and cultural centre. Large churches, lavishly decorated inside, were built, and friars from various orders were present. The urban complex in the remote Andes was important enough to be designated a Villa Imperial in the hierarchy of Spanish urban settlements. The core of Potosí was laid out in the standard Spanish grid pattern, and by 1610, some 3,000 Spaniards and 35,000 creoles, mostly male, were resident. Indigenous settlements outside the core were more haphazard.

Today, Potosí continues to be an important mining centre and is the largest urban centre in the Department of Potosí. It is now famous for its well-preserved colonial architecture and unusual geographic setting as one of the highest cities in the world.

Exploring La Paz, Bolivia: How Long Should You Stay?

You may want to see also

The impact of mining on the indigenous population

Mining has had a significant impact on the indigenous population of Bolivia, particularly in Potosí. Here is an overview of the effects:

Forced Labour

Indigenous labourers were forced to work in the silver mines of Potosí under the Spanish mita system of forced labour, based on an analogous mit'a system from pre-Hispanic Andean society. This system conscripted about one out of every seven adult males in the indigenous population, subjecting them to harsh and dangerous conditions. They were given the most undesirable jobs, such as carrying heavy loads of ore up steep, narrow shafts. This led to numerous injuries and deaths from falls and accidents. Additionally, the rapid temperature changes and high altitude made them susceptible to illnesses like pneumonia. The harsh conditions also resulted in demographic shifts, as families moved with workers to Potosí, while others fled their traditional villages, leading to a significant decline in the local indigenous population.

Health Risks

The mining activities in Bolivia have exposed the indigenous population to contamination by various metals, including cadmium, lead, mercury, antimony, nickel, cobalt, chromium, zinc, copper, and arsenic. These pollutants are present in the air, water, and soil, leading to health risks, especially for children who are more vulnerable due to their size and immature physiology. The impact of this contamination has been known for decades, if not centuries, but it is challenging to quantify due to the region's naturally rich metal concentrations in the soil and multiple sources of contamination.

Environmental Degradation

Mining has also led to environmental degradation in the area. For example, the wind erosion of spoil heaps and the transport of ore by uncovered trucks or trains have spread metal trace elements over long distances. Additionally, the degradation of Cerro de Potosí (also known as Cerro Rico or Sumaj Orcko) due to continuous mining operations has been a concern, as the mountain has become porous and unstable.

Social and Cultural Impact

The presence of mining in Bolivia has also influenced social and cultural aspects of indigenous communities. The development of the mining industry led to the separation of Spanish colonists and forced labourers, with an artificial river dividing their respective zones. Additionally, a strong identity has been forged around the mine, with traditions, a way of life, and even a carnival. However, this has also led to an underestimation of the problems caused by mining, as the economic and cultural significance of mining can outweigh the recognition of its negative consequences.

Exploring Bolivia's Longest Rivers: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

The decline of mining in Potosí

Depletion of Rich Surface Ores:

By 1565, miners in Potosí had exhausted the easily accessible, rich oxidized ores that could be directly fed into smelting furnaces. This depletion led to a significant drop in silver production, as the remaining ores were located deeper in the mountain and required more complex extraction methods.

Transition to Tin Mining:

In 1891, Potosí underwent a transition from silver mining to tin mining due to declining silver prices. This shift in focus continued until 1985, marking a move away from the city's historical association with silver extraction.

Social and Political Changes:

The forced labor system, known as the "mita," faced strong opposition and eventually came to an end. This system had been a source of labor for the mines, but it caused demographic shifts and led to harsh working conditions for indigenous laborers. By the late 17th century, the local indigenous population had decreased significantly, and the number of laborers available decreased as well.

Competition and Alternative Sources:

The discovery and development of alternative sources of silver and other minerals in places like Guanajuato, Mexico, and Huancavelica, Peru, reduced the reliance on Potosí as the primary source.

Scandals and Loss of Confidence:

In the 1630s, debased silver bars and coins from Potosí were rejected by bankers in Genoa and Antwerp, leading to a loss of confidence in the value of its currency. This scandal further contributed to the decline in the region's mining prominence.

Environmental Concerns:

The continued mining of Cerro Rico, also known as the "Rich Mountain," has raised concerns about the preservation of its form, topography, and natural environment. Hundreds of years of mining have left the mountain porous and unstable, posing challenges to sustainable mining practices.

Bolivia's Education System: Free for All?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

There are topographic maps of Potosí, Bolivia. The Instituto Geográfico Militar (IGMB) in La Paz, Bolivia, is responsible for topographic mapping in the country.

Potosí is located at an elevation of 3,888 m (12,756 ft) or 4,050 m (13,290 ft). It is one of the highest cities in the world.

Potosí is known for its rich history and cultural significance. It is famous for its mining activities, particularly the extraction of silver ore from the Cerro Rico ("Rich Mountain"). The city has a well-preserved colonial architecture and is recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.