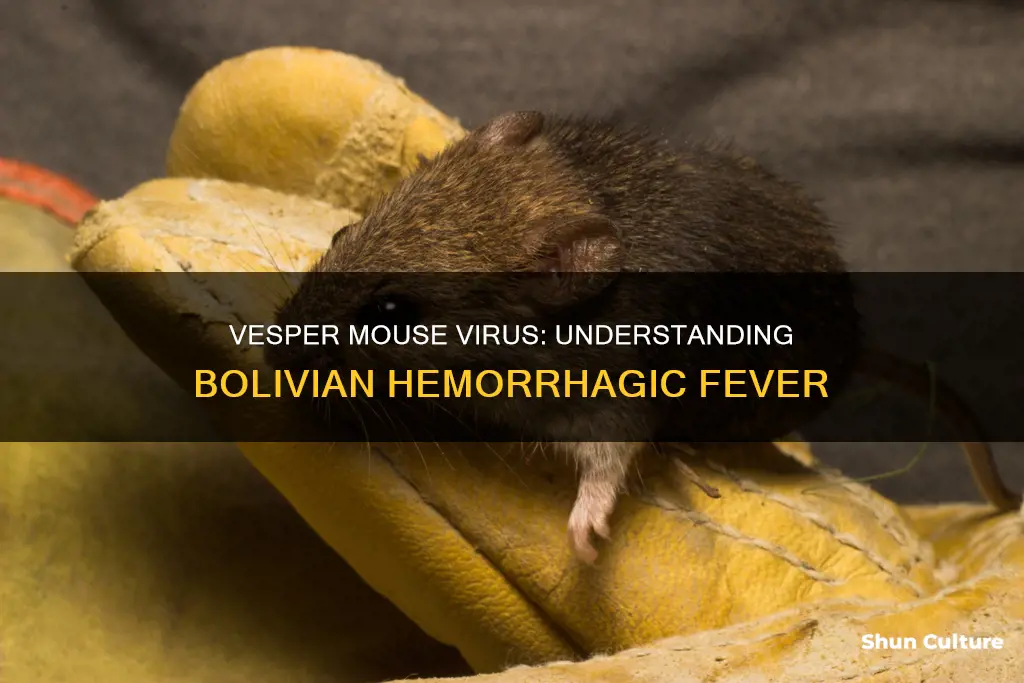

Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever (BHF) is a hemorrhagic fever and zoonotic infectious disease originating in Bolivia. The disease was first encountered in 1962 in the Bolivian village of San Joaquín and is caused by the Machupo mammarenavirus. The virus was identified by a team of researchers led by Dr. Karl Johnson, an American virologist working with the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) at the time. The large vesper mouse (Calomys callosus), a rodent indigenous to northern Bolivia, is the primary vector and reservoir for the virus. Infected animals are asymptomatic and spread the virus through their excreta, thereby infecting humans.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Virus name | Machupo virus (MACV) |

| Virus family | Arenaviridae |

| Virus type | Enveloped, bi-segmented, negative-sense RNA virus |

| Virus structure | Pleomorphic |

| Genome structure | Ambisense |

| Genome segments | Long (L) and short (S) |

| Geographical range | Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina |

| Natural vector and reservoir | Calomys callosus (large) vesper mouse |

| Transmission | Aerosolized excreta, contaminated food, mucus membrane contact, human-to-human |

| Incubation period | 3-16 days |

| Symptoms | Fever, malaise, myalgia, headache, anorexia, vomiting, hypersensitivity, vascular damage, neurological issues |

| Mortality rate | 25-35% |

| Treatment | Supportive care, convalescent immune plasma, human immunoglobulin, ribavirin |

What You'll Learn

- The Machupo virus, a member of the Arenaviridae family, is the cause of Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever

- The Calomys callosus, a large vesper mouse, is the primary vector and reservoir for the Machupo virus

- The virus was first discovered in 1959 in San Joaquin, Bolivia

- The disease has a high mortality rate of up to 35%

- There is currently no cure or vaccine for Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever

The Machupo virus, a member of the Arenaviridae family, is the cause of Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever

The Machupo virus is an enveloped RNA virus, and is considered highly dangerous. It is classified as a Category A pathogen by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), requiring Biosafety Level Four conditions, the highest level. This makes studying the virus challenging, and research is limited.

The infection has a slow onset, with symptoms including fever, malaise, headache, and myalgia. As the disease progresses, patients may experience petechiae (blood spots) on the upper body, as well as bleeding from the nose and gums. About one-third of patients will develop severe hemorrhagic or neurologic symptoms, including tremors, delirium, and convulsions. The mortality rate is estimated to be between 5 and 35 percent.

There is currently no cure or vaccine for BHF, although a vaccine developed for the related Junín virus, which causes Argentine hemorrhagic fever, has shown some promise as a prophylactic measure. Preventative measures such as rodent control have been effective in reducing the number of outbreaks.

Bolivia's Unique Claims to Fame

You may want to see also

The Calomys callosus, a large vesper mouse, is the primary vector and reservoir for the Machupo virus

The Calomys callosus is a rodent that carries the Machupo virus asymptomatically, shedding it in its excreta and infecting humans. This method of transmission is similar to other South American hemorrhagic arenaviruses. The virus can also spread through inhalation of infectious aerosols, direct contact with broken skin or mucous membranes, or contaminated food or fomites. While person-to-person transmission is possible, it is believed to be rare.

The Calomys callosus thrives in villages and near human habitations, particularly in areas where grassland intergrades into forest. This makes it more likely to come into contact with humans and contribute to outbreaks of BHF. The risk of infection is higher for those who have frequent contact with rodent excreta, especially through agricultural and domestic exposures.

BHF typically occurs in seasonal patterns, with more cases reported during the dry season when agricultural activity is at its peak. The disease has a high mortality rate, ranging from 5% to 35%. The clinical symptoms of BHF include fever, malaise, headache, myalgia, and gastrointestinal issues. In severe cases, neurological and hemorrhagic symptoms such as tremors, delirium, and convulsions may occur, along with bleeding.

To control the spread of BHF, measures such as rodent control and trapping have been implemented in affected areas. These measures have been effective in reducing the number of outbreaks and limiting the spread of the disease. However, sustaining these programs over the long term can be challenging.

The development of vaccines and treatments for BHF is ongoing, but currently, there is no cure or FDA-approved vaccine for the disease. Ribavirin, an antiviral therapeutic, has shown some promise, but more research is needed to determine its effectiveness. Preventative measures, such as raising awareness and educating people in affected areas, remain crucial in controlling the spread of BHF.

Bolivia's Currency: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

The virus was first discovered in 1959 in San Joaquin, Bolivia

The Machupo virus, which causes Bolivian hemorrhagic fever, was first discovered in 1959 in San Joaquin, Bolivia. The discovery was made by a team of researchers led by Dr Karl Johnson, an American virologist working with the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The virus was named after the Machupo River near San Joaquin, where the outbreaks were discovered.

The Machupo virus is an enveloped RNA virus of the Arenaviridae family. It is transmitted to humans from rodents, specifically the Calomys callosus, a type of vesper mouse common in the area. The discovery of the Machupo virus was a major breakthrough, helping to control the outbreak in Bolivia and improving our understanding of hemorrhagic fevers caused by arenaviruses.

The first outbreak of Machupo virus in Bolivia lasted from 1959 to 1963, with 500 cases reported and 90 deaths. The virus was identified as the cause of the outbreak in 1963, and rodent control measures were implemented, successfully preventing further outbreaks until the 1990s.

Bolivian hemorrhagic fever is a severe and potentially fatal disease. It has a high mortality rate, ranging from 5% to 35%. The infection has a slow onset, with initial symptoms including fever, malaise, headache, and myalgia, similar to malaria. As the disease progresses, patients may experience petechiae (blood spots) and bleeding from the nose and gums. Severe hemorrhagic or neurologic symptoms may develop, including tremors, delirium, and convulsions.

The discovery of the Machupo virus in 1959 was a significant moment in the field of virology and disease control. It led to a better understanding of hemorrhagic fevers and guided control measures to prevent further outbreaks. The work of Dr Karl Johnson and his team played a crucial role in managing the outbreak and improving public health in the affected region.

The Machupo virus remains a significant health concern in Bolivia, with sporadic cases and outbreaks occurring over the years. The virus's high mortality rate and potential for human-to-human transmission underscore the importance of ongoing research, surveillance, and preventive measures to protect public health.

Exploring Bolivia's Second-Largest City: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

The disease has a high mortality rate of up to 35%

The Machupo virus, which causes Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever (BHF), has a mortality rate of 25 to 35%. This high death rate, combined with the fact that there is no cure, means that BHF is a significant disease, despite being rare.

The first outbreak of BHF was reported in Bolivia between 1959 and 1964, with over 1,000 cases identified by 1962. The virus was identified by a team of researchers led by Dr. Karl Johnson. The name Machupo comes from the Machupo River near San Joaquin, Bolivia, where the initial outbreaks occurred.

BHF is transmitted to humans from rodents, specifically the Calomys callosus, a type of vesper mouse common in the area. The disease is seasonal, with more cases occurring during the dry season when agricultural activity is at its peak. This is because the rodent host thrives in villages and near human habitations.

The incubation period for BHF is 3 to 16 days, after which the first symptoms appear. These include fever, malaise, myalgia, headache, and anorexia. This develops into more severe symptoms such as vomiting, hypersensitivity, and early signs of vascular damage. Approximately one-third of patients then develop severe neurological or hemorrhagic symptoms within a week, including bleeding gums, coma, and death.

The high mortality rate of BHF is due to the lack of a cure or vaccine and the fact that it is easily transmitted from rodents to humans. The best prevention method is to control the rodent population in affected areas. This was successful in the 1970s and early 1990s, but cases have re-emerged in recent years, highlighting the need for further research and the development of a vaccine.

Exploring Bolivia's Wettest Seasons and Months

You may want to see also

There is currently no cure or vaccine for Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever

Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever (BHF) is a severe illness with a high mortality rate of up to 35%. It is caused by the Machupo virus (MACV), an enveloped RNA virus of the Arenaviridae family. This virus was first identified in 1963 by a research group led by Karl Johnson, and it is named after the Machupo River near San Joaquin, Bolivia, where the initial outbreaks occurred.

Currently, there is no cure or vaccine specifically designed for BHF that has been approved for human use. The disease is considered a severe health threat, with a high death rate ranging from 5% to 35%. The lack of a cure or vaccine poses a significant challenge in managing and preventing BHF outbreaks.

While there is no specific cure or vaccine for BHF, some measures have been implemented to control the disease. These include rodent population control, as the virus is transmitted to humans from infected rodents, specifically the Calomys callosus, a type of vesper mouse common in Bolivia. Additionally, a vaccine developed for the genetically related Junín virus, which causes Argentine hemorrhagic fever, has shown cross-reactivity to the Machupo virus. This vaccine may provide some protection for people at high risk of infection.

The absence of a cure or vaccine for BHF highlights the ongoing need for research and development in this area. It underscores the importance of prevention and control measures, such as rodent control, awareness, and education in affected areas, to prevent outbreaks and reduce the impact of this deadly disease.

The scientific community is actively working to improve the understanding of the Machupo virus, develop effective treatments, and create a vaccine to protect the general population.

Tiwanaku, Bolivia: An Ancient Site's Age and History

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever (BHF) is a severe illness with a high mortality rate, caused by the Machupo virus. It is characterised by fever, myalgia, and arthralgia followed by hemorrhagic and neurological manifestations.

The disease has a slow onset with fever, malaise, headache, and myalgia, similar to Malaria symptoms. As the disease progresses to the hemorrhagic phase, usually within seven days, petechiae (blood spots) on the upper body, and bleeding from the nose and gums are observed. About one-third of patients develop severe neurological or hemorrhagic symptoms such as tremors, delirium, and convulsions.

Currently, there is no cure or vaccine for BHF. Treatment is focused on supportive care and fluid administration. A vaccine for the related Junín virus, which causes Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever, has shown some cross-reactivity to the Machupo virus and may be an effective prophylactic measure.

The large vesper mouse (Calomys callosus), a rodent indigenous to northern Bolivia, is the primary vector and reservoir for the Machupo virus. The virus is transmitted to humans through inhalation of aerosolised excreta, consumption of contaminated food, or direct contact with infected particles.

Measures to reduce contact between the vesper mouse and humans, such as rodent control, have been effective in limiting the number of outbreaks. Education and awareness in affected areas are also important in preventing outbreaks.