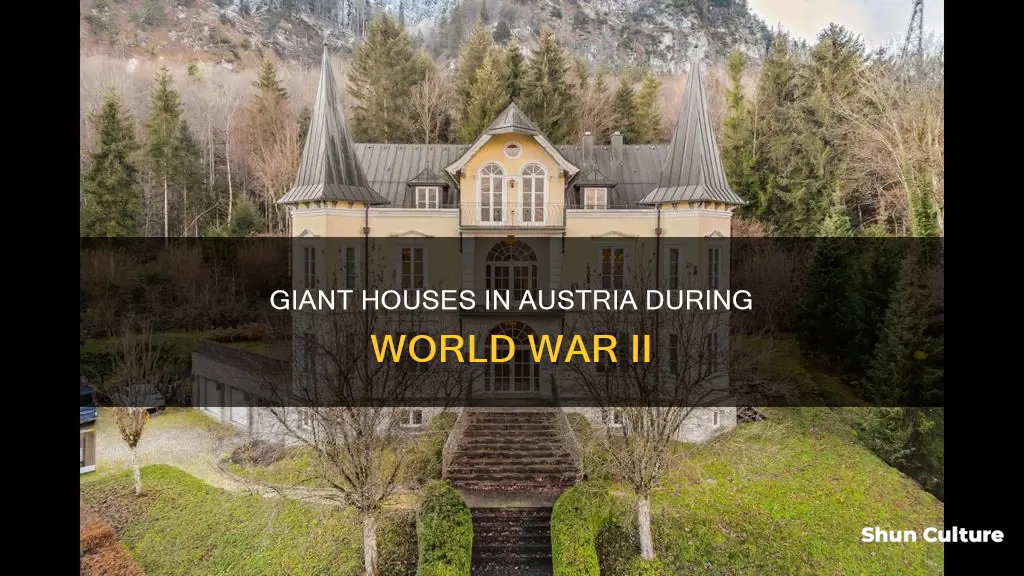

During World War II, there were giant houses in Austria, notably Adolf Hitler's holiday home, Berghof, in the Obersalzberg of the Bavarian Alps near Berchtesgaden, Germany. The house was initially a small chalet called Haus Wachenfeld, which Hitler rented in 1928 and later purchased in 1933. In 1935, Hitler began renovating and expanding the house, and by 1936, it had been transformed into a sprawling landhaus with a bowling alley in the cellar and a giant window offering panoramic views of the snow-capped mountains in Hitler's native Austria. The house became a centrepiece of Nazi propaganda, with the German-controlled press portraying Hitler's life at home in a positive light, softening his image and presenting him as a man of culture, a dog lover, and a good neighbour.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Location | Obersalzberg, Germany, near the Austrian border |

| Type of building | Holiday home |

| Owner | Adolf Hitler |

| Other names | Berghof, Mountain Court |

| Previous name | Haus Wachenfeld |

| Previous owner | Kommerzienrat Otto Winter |

| Year of construction | 1916 or 1917 |

| Year of renovation | 1935-1936 |

| Renovation architect | Alois Degano |

| Renovation supervisor | Martin Bormann |

| Interior designer | Gerdy Troost |

| Year of destruction | 1945 |

What You'll Learn

Hitler's holiday home, the Berghof, in the Obersalzberg of the Bavarian Alps

Hitler's holiday home, the Berghof, was located in the Obersalzberg of the Bavarian Alps, near Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, Germany. The area is a mountainside retreat situated above the market town of Berchtesgaden, about 120 kilometres (75 mi) southeast of Munich, close to the border with Austria.

The Berghof began as a much smaller chalet called Haus Wachenfeld, a holiday home built in 1916 or 1917 by businessman Kommerzienrat Otto Winter. In 1928, Winter's widow rented Haus Wachenfeld to Hitler, and his half-sister Angela came to live there as a housekeeper. By 1933, Hitler had purchased the chalet with funds from the sale of his political manifesto, Mein Kampf. The small chalet-style building was then refurbished and expanded by architect Alois Degano during 1935-36 under the supervision of Martin Bormann. It was renamed The Berghof, or Mountain Court in English.

The renovated interiors were designed by Gerdy Troost. The house featured a large terrace with colourful, resort-style canvas umbrellas. The entrance hall had a display of cactus plants in majolica pots, and the dining room was panelled with expensive cembra pine. Hitler's large study had a telephone switchboard room, and the library contained books on history, painting, architecture, and music. The great hall was furnished with expensive Teutonic furniture, a large globe, and a red marble fireplace mantel. A sprawling picture window could be lowered into the wall to give a panoramic view of the snow-capped mountains in Hitler's native Austria. The house was maintained by several housekeepers, gardeners, cooks, and other domestic workers.

The Berghof became a centrepiece of Nazi propaganda, with the Nazi-controlled German press and international media portraying Hitler's life at home in a positive light. The area became a German tourist attraction during the mid-1930s, with visitors gathering near the residence in the hope of catching a glimpse of Hitler. This led to the introduction of severe restrictions on access to the area and other security measures.

The Berghof was damaged by British bombs in April 1945 and then again by retreating SS troops in early May. It was looted after Allied troops reached the area. The Bavarian government demolished the burned shell in 1952 to prevent it from becoming a neo-Nazi shrine.

Hermes Bangle: Austrian-Made?

You may want to see also

The Anschluss and Austria's absorption into Germany

The annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany, known as the Anschluss, took place on March 12, 1938. The idea of a union between Austria and Germany, resulting in a “Greater Germany”, had been proposed since the unification of Germany in 1871, which excluded Austria and German Austrians from the new Prussian-dominated German Empire.

After the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, the Republic of German-Austria attempted to unite with Germany, but the Treaty of Saint Germain and the Treaty of Versailles prohibited this. The idea of a union gained support in the 1920s, particularly among Austrian citizens of the political left and centre, who believed that Austria, stripped of its imperial land, was not economically viable. However, support for unification faded over time.

When Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany in 1933, the desire for unification became associated with the Nazis, for whom it was an integral part of their ideology. Hitler himself, an Austrian German by birth, had written in his 1925 book Mein Kampf that he would unite Austria and Germany by any means possible. In 1938, Hitler pressured Austrian chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg to appoint members of the Austrian Nazi Party to his cabinet and give them full political rights, threatening to invade if he did not comply.

Fearing that Hitler intended to take over Austria, Schuschnigg called for a national plebiscite, or vote, to take place on March 13, 1938, to allow Austrians to decide whether they wanted their nation to remain independent or become part of the Third Reich. Hitler decided to invade Austria immediately to prevent the vote. On March 11, Schuschnigg cancelled the plebiscite and offered to resign to avoid bloodshed, but Hitler demanded that Austrian president Wilhelm Miklas appoint an Austrian Nazi as the nation's next chancellor. When Miklas refused, Hitler ordered the invasion to begin at dawn on March 12.

On the morning of March 12, German soldiers in tanks and armoured vehicles crossed the Austrian border, encountering no resistance. Hitler himself arrived later that day, visiting his birthplace and his parents' grave. On March 15, he gave a speech in Vienna, declaring that Austria was now part of the German Empire: the Anschluss. Austria had become a German province called Ostmark, and Hitler appointed Arthur Seyss-Inquart as governor.

On April 10, 1938, the Nazis organised a referendum to legitimise their military action, with more than 99% of the Austrian population voting in favour of the union. However, the vote was not anonymous, and opponents did not dare to vote against. The takeover allowed the Austrian Nazis to openly express their antisemitism, and many Jews tried to flee the country.

Upgrading Austrian Airlines Tickets: A Simple Guide to Comfort

You may want to see also

The persecution and deportation of Austrian Jews

Persecution

Austrian Jews faced extreme intimidation, violence, and wild expropriation of their property. They were disenfranchised and no longer allowed on public transport. Many were forced into humiliating labour, such as cleaning sidewalks and public toilets, sometimes with toothbrushes or their bare hands. In one instance, Jews were forced to eat grass at the Prater, a popular Viennese amusement park.

Deportation

The deportation of Austrian Jews to Poland began in October 1939, with 1,584 people sent to the Lublin region. The first deportations of Austrian Jews to concentration camps began in October 1939, with about 1,500 Jews deported to Nisko. Few returned. In February and March 1941, another 5,000 were deported to Poland (Opole, Kielce, Modliborzyce, and Lagow).

Resistance and Rescue

While many Austrians participated in the Nazi regime, a small minority of the Austrian population actively resisted Nazism. The Austrian historian Helmut Konrad estimates that out of a population of 6.8 million in 1938, there were around 100,000 Austrian opponents to the regime.

One notable example of resistance is the group led by the priest Heinrich Maier. This Catholic resistance group aimed to revive a Habsburg monarchy after the war and passed on plans and production facilities for V-2 rockets, Tiger tanks, and aircraft to the Allies. The group also informed the Allies about the mass murder of Jews, thanks to their contacts with the Semperit factory near Auschwitz.

Post-War

After the war, the Austrian Jewish community was slow to recover. By 1945, only around 5,000 Jews remained in Austria, and by 1950, the Jewish community numbered 13,396 people. The Kultusgemeinde, the only remaining Jewish community in Austria, struggled financially, as it could no longer rely on taxation and investments to meet its budget.

In the first years after the war, memorials were built to commemorate the dead soldiers of World War II, while memorials for the victims of the Nazi regime were only built much later. Austrian society also adhered to the "First Victim" narrative, portraying Austria as a victim rather than an enthusiastic supporter of Nazi Germany, thus sidestepping responsibility for the crimes of the Third Reich.

Immigration in Salzburg, Austria: What's the Situation?

You may want to see also

The role of Austrians in the Nazi war machine

Austrians played a significant role in the Nazi war machine, both as perpetrators and victims.

The Nazi Annexation of Austria

Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany in March 1938 in an event known as the Anschluss. This was the first act of territorial aggression by Nazi Germany, violating the Treaty of Versailles and the Treaty of Saint-Germain, which expressly forbade the unification of the two countries. The annexation was widely popular in both Germany and Austria, with most Austrians enthusiastically welcoming German troops.

Austrians in the Nazi Regime

Many Austrians participated in the Nazi administration, from senior leadership positions to personnel in death camps. Austrians made up about 8% of the population of Nazi Germany, but they were disproportionately represented in the SS (13%) and concentration camp personnel (40%). Additionally, 75% of concentration camp commanders were Austrian. Notable Austrians in the Nazi regime included Adolf Hitler, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, Odilo Globocnik, and Franz Josef Huber.

Austrians in the Military

During World War II, 950,000 Austrians fought for the Nazi German armed forces, and 150,000 joined the Waffen-SS, the military wing of the Nazi Party. Hundreds of thousands of Austrians fought as German soldiers, and a substantial number served in the elite military corps of the Nazi Party, the SS.

Austrian Resistance

A small minority of Austrians actively participated in the resistance against Nazism. The Austrian resistance groups were often ideologically separated and reflected the spectrum of political parties before the war. In addition to armed resistance groups, there were communist, Catholic, Habsburg, and individual resistance groups within the German Wehrmacht. Most resistance groups were exposed by the Gestapo and their members executed.

Austrian Victims of Nazi Persecution

Austrian Jews, Roma (Gypsies), and people with mental or physical disabilities were victims of Nazi persecution. Many Austrians, especially those of Jewish origin, were forced into exile. During the war, more than 100,000 Jews left Austria, and over 65,000 Austrian Jews perished, many in extermination camps. Thousands of Roma were deported or murdered, and tens of thousands of Austrians with disabilities were killed, often in "euthanasia" centres.

Post-War Austria

After World War II, Austria sought to distance itself from the Nazis and advance the view that it was the first victim of Nazi aggression. However, it was not until the 1990s that Austria officially abandoned the "victim theory" and admitted its collective responsibility for the crimes committed during the Nazi occupation.

US Citizens: Can They Enter Austria or Not?

You may want to see also

The Soviet occupation of Austria

The Soviet Union's occupation of Austria was shaped by the Moscow Declaration of 1943, in which the British, Americans, and Soviets proclaimed that Austria was the first victim of Nazi Germany. However, the declaration also acknowledged Austria's participation in Nazi aggression and stated that it would have to pay the price for its role.

On 29 March 1945, Soviet commander Fyodor Tolbukhin's troops crossed the former Austrian border at Klostermarienberg in Burgenland. On 3 April, at the beginning of the Vienna Offensive, the Austrian politician Karl Renner, then living in southern Lower Austria, established contact with the Soviets. On 20 April 1945, the Soviets instructed Renner to form a provisional government without consulting their Western allies. Renner's cabinet took office on 27 April, declaring Austria's independence from Nazi Germany and calling for the creation of a democratic state along the lines of the First Austrian Republic.

Soviet occupation policies in Austria were influenced by the notion that Austria was a victim of Germany, and thus, Austria avoided some of the harsh consequences faced by Germany. Austria did not lose any territory, and Austrians were not expelled or subjected to ethnic cleansing. Additionally, the Western Allies opposed the Kremlin's plans for burdensome war reparations on Austria. However, the Western Allies did consent to Moscow's demand for German assets in Austria within their zone of occupation.

The Red Army occupied only parts of Austria, including the capital Vienna, while Anglo-American troops entered from Germany and Italy. Thereafter, France, Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union divided Austria into four occupation zones. The Soviets did not attempt to impose a communist dictatorship in Austria, and their zone of occupation experienced less political violence compared to other countries occupied by the Red Army. According to research, during the initial eight months of occupation, Soviet military tribunals arrested around 800 Austrian civilians, with charges ranging from belonging to the Nazi Werewolf resistance group to espionage and war crimes.

The scale of looting, rapes, and assaults committed by Soviet troops in Austria was significant. The Red Army suffered 94,185 casualties in Austria, and their conduct towards civilians included widespread sexual violence, robberies, and murders. However, as the war turned into occupation, the sexual relations between Soviet men and Austrian women became less physically violent and more transactional, and in some instances, consensual.

The Soviets pulled out of Austria in 1955, along with the Western Allies, after Austria pledged to remain neutral in the Cold War and maintain the Soviet War Memorial in Vienna.

Austrian Residents: How to Get a Passport

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, there were several large houses in Austria during World War II, including the homes of high-ranking Nazi officials and Adolf Hitler's residence, the Berghof.

The giant houses in Austria during World War II were typically owned by wealthy individuals, Nazi officials, and members of the upper class.

Many of the giant houses in Austria were confiscated, looted, or destroyed during and after World War II. Some were demolished in the 1950s to prevent them from becoming Nazi shrines.

The giant houses in Austria during World War II often featured luxurious designs, sprawling land, and extravagant amenities. For example, Hitler's Berghof residence had a bowling alley in the cellar and a giant window that provided panoramic views of the mountains.

Yes, the giant houses, especially Hitler's Berghof, became a centerpiece of Nazi propaganda. The Nazi-controlled press portrayed Hitler's life at home in a positive light, aiming to soften his image and present him as a cultured and friendly leader.