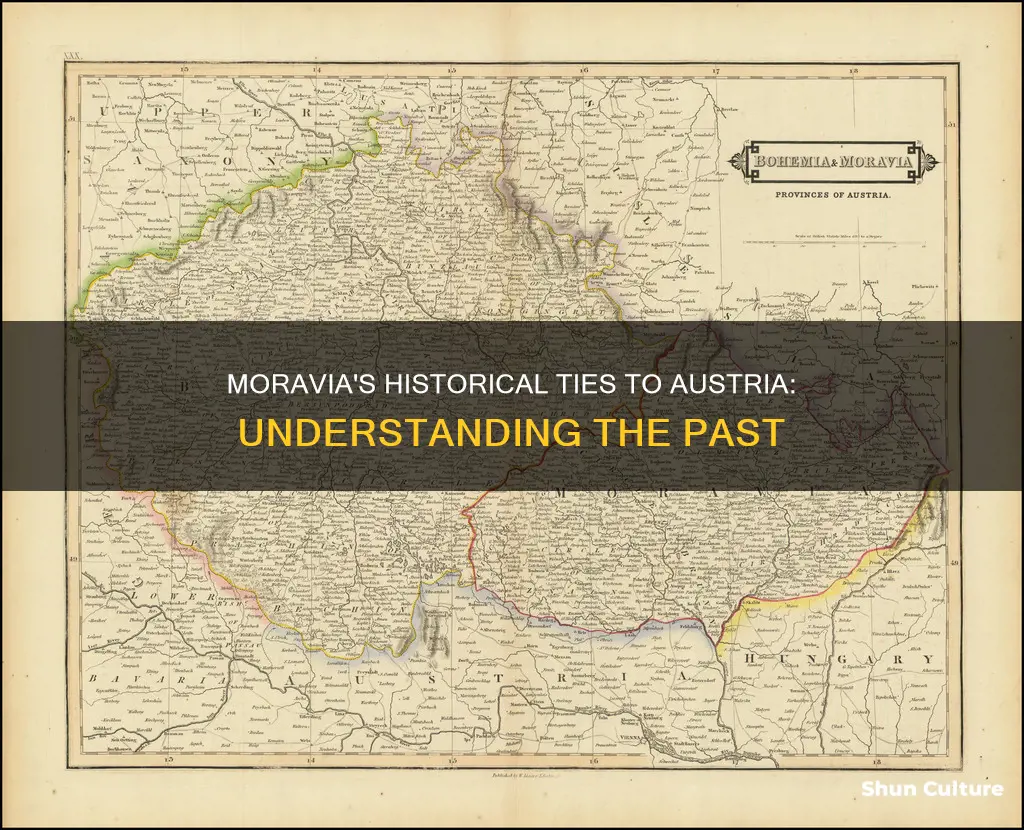

Moravia, a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic, has been a part of Austria at various points in its history. From 1348 to 1918, it was a crown land of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown, and from 1804 to 1867, it was a crown land of the Austrian Empire. From 1867 to 1918, Moravia was one of the crown lands of the Cisleithanian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Part of Austria-Hungary | 1867-1918 |

| Part of Czechoslovakia | 1918-1938 |

| Part of Nazi Germany | 1938-1945 |

| Part of Czechoslovakia | 1945-1993 |

| Part of the Czech Republic | 1993-present |

What You'll Learn

- Moravia was a crown land of the Austrian Empire from 1804 to 1867

- It was then briefly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1867 to 1918

- After World War I, Moravia became part of Czechoslovakia

- During World War II, it was annexed by Nazi Germany

- After World War II, the ethnic German minority of Moravia was expelled

Moravia was a crown land of the Austrian Empire from 1804 to 1867

Moravia, a historical country in the Czech Republic, was a crown land of the Austrian Empire from 1804 to 1867. During this period, Moravia was ruled by the Austrian Habsburgs, who had claimed it through inheritance in 1526.

Moravia was a part of the Austrian Empire during a time of increasing animosity between the Catholic Habsburg kings and the Protestant Moravian nobility. From 1599 to 1711, Moravia was frequently subjected to raids by the Ottoman Empire and its vassals, resulting in the enslavement and death of thousands. In the 17th century, Moravia established the oldest surviving theatre building in Central Europe, the Reduta Theatre.

In 1740, Moravia was invaded by Prussian forces under Frederick the Great, and its capital, Olomouc, was forced to surrender. However, the Prussians were ultimately repelled, due to their unsuccessful siege of Brno in 1742. In 1758, Olomouc faced another siege by Prussian forces but successfully defended itself, forcing the Prussians to withdraw.

In 1782, the Margraviate of Moravia was merged with Austrian Silesia to form Moravia-Silesia, with Brno as its capital. This merger lasted until 1850. During the Revolution of 1848, the Habsburgs reaffirmed Moravia's status as a separate Austrian crown land.

Address Writing in Austria: A Guide to the Proper Format

You may want to see also

It was then briefly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1867 to 1918

Moravia was a crown land of the Austrian Empire from 1804 to 1867. In 1867, it became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was formed when the Austrian Empire was reformed into a dual monarchy, with two equal components: Austria and Hungary. From 1867 to 1918, Moravia was one of the 17 former crown lands of the Cisleithanian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

During this period, Moravia was administratively detached from Bohemia. However, it was still closely connected to it, as both lands were ruled by the Austrian Habsburgs. The Moravian margraviate was merged with Austrian Silesia into Moravia-Silesia, with Brno as its capital.

In 1918, following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Moravia became a province of the newly formed state of Czechoslovakia.

Beethoven's Austrian Roots: Where Was He Born?

You may want to see also

After World War I, Moravia became part of Czechoslovakia

Moravia, a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic, was a crown land of the Austrian Empire from 1804 to 1867. It then became part of Austria-Hungary from 1867 to 1918. After World War I, Moravia became part of Czechoslovakia, along with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

Moravia was one of the five lands of Czechoslovakia, founded in 1918, and enjoyed restricted autonomy. In 1928, it was merged with Czech Silesia and then dissolved in 1948 during the abolition of the land system following the communist coup d'état.

Moravia has a rich history, dating back to the Paleolithic period when early modern humans settled in the region. Over the centuries, it has been inhabited by various tribes and groups, including the Celtic Volcae, the Germanic Quadi, and the Avars. The Slavs, who gave the region its name, established themselves in the territory in the 6th century.

During the medieval period, Moravia was a significant part of the Great Moravian Empire, which encompassed much of present-day Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Germany. After the fall of Great Moravia in the 10th century, Moravia's history became closely intertwined with that of Bohemia. The region was ruled by various dynasties, including the Přemyslids, Luxembourgs, and Habsburgs, until the end of World War I.

Today, Moravia is no longer a separate political entity but remains an important cultural and historical region within the Czech Republic, with a distinct identity and a strong sense of Moravian nationalism among its inhabitants.

Apple Availability in Austria: A Comprehensive Overview

You may want to see also

During World War II, it was annexed by Nazi Germany

During World War II, Moravia was annexed by Nazi Germany. The region was divided, with the area containing more ethnic Germans absorbed by the German Third Reich, and the rest of the region made into an administrative unit within the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The Protectorate was a partially-annexed territory of Nazi Germany, established on 16 March 1939, after the German occupation of the Czech lands. The population of the Protectorate was mostly ethnic Czech, but ethnic Germans were offered Reich citizenship, while Jews and Czechs were considered second-class citizens.

The Protectorate was ruled by a puppet Czech administration, with real power lying with the Nazi authorities. The Czech economy was put to work for the German war effort, and the Protectorate administration was deeply involved in the Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia. The Czech population was subjected to rationing, and the Czech crown was devalued to the Reichsmark. Inflation was a major problem throughout the existence of the Protectorate, and living standards decreased.

Under the Protectorate, the Gestapo directed its activities against Czech politicians and the intelligentsia. In 1940, a secret plan on the Germanisation of the Protectorate declared that those considered racially Mongoloid and the Czech intelligentsia were not to be Germanised, and that about half of the Czech population were suitable for Germanisation. The Czech intellectual elite were to be removed from Czech territories and from Europe entirely. The Nazis believed that a large swathe of the Czech populace was "capable of Aryanisation", and this belief was supported by the view that part of the Czech population had German ancestry.

In 1941, Hitler decided that the Reich Protector, Konstantin von Neurath, was not treating the Czechs harshly enough, and so he appointed SS hardliner Reinhard Heydrich as Deputy Reich Protector. Heydrich replaced Neurath as the de facto Reich Protector, and under his authority, the Czech government was reorganised, and all Czech cultural organisations were closed. The Gestapo arrested and murdered people, and the deportation of Jews to concentration camps was organised. The fortress town of Terezín was made into a ghetto way-station for Jewish families.

In 1942, Heydrich died after being wounded by Czechoslovak commandos. Directives issued by his successor, Kurt Daluege, brought forth mass arrests, executions, and the obliteration of the villages of Lidice and Ležáky. In 1943, the German war effort was accelerated, and all non-war-related industry was prohibited. Most of the Czech population obeyed quietly until the final months preceding the end of the war, when thousands became involved in the resistance movement.

The number of Czech victims of political persecution and murders in concentration camps totalled between 36,000 and 55,000. The Jewish population of Bohemia and Moravia (118,000 according to the 1930 census) was virtually annihilated, with over 75,000 murdered.

Austria-Hungary's Imperial Ambitions: Colonies and Conquests

You may want to see also

After World War II, the ethnic German minority of Moravia was expelled

Moravia, a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic, was a crown land of the Austrian Empire from 1804 to 1867 and part of Austria-Hungary from 1867 to 1918. After World War I, Moravia became one of the five lands of Czechoslovakia.

During World War II, the Czechoslovak government-in-exile sought the support of the Allies for the expulsion of the German population from Czechoslovakia. The decision to deport the Germans was reached at the Potsdam Conference on 2 August 1945. The Potsdam Agreement stated that:

> "The Three Governments, having considered the question in all its aspects, recognize that the transfer to Germany of German populations, or elements thereof, remaining in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, will have to be undertaken. They agree that any transfers that take place should be effected in an orderly and humane manner."

In the months following the end of the war, "wild" expulsions happened from May until August 1945. Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš called for the "final solution of the German question", which would be achieved by the deportation of the ethnic Germans from Czechoslovakia. The expulsions were carried out by order of local authorities, mostly by groups of armed volunteers, and sometimes with the assistance of the regular army. Several thousand died violently during the expulsion, and more died from hunger and illness as a consequence. The expulsion according to the Potsdam Conference proceeded from 25 January 1946 until October of that year. Roughly 1.3 million ethnic Germans were deported to the American zone (West Germany), and an estimated 800,000 were deported to the Soviet zone (East Germany).

The expulsions ended in 1948, but not all Germans were expelled; estimates for the total number of non-expulsions range from approximately 160,000 to 250,000. The German Church Search Service was able to confirm the deaths of 14,215 persons during the expulsions from Czechoslovakia (6,316 violent deaths, 6,989 in internment camps and 907 in the USSR as forced labourers). The joint German and Czech commission of historians estimated that there were about 15,000 violent deaths. Czech records report 15,000–16,000 deaths not including an additional 6,667 unexplained cases or suicides during the expulsion, and others died from hunger and illness in Germany as a consequence.

In 1995, research by a joint German and Czech commission of historians found that the previous demographic estimates of 220,000 to 270,000 deaths were overstated and based on faulty information. They concluded that the actual death toll was at least 15,000 people and that it could range up to a maximum of 30,000 dead, assuming that not all deaths were reported. The West German government in 1958 estimated the ethnic German death toll during the expulsion period to be about 270,000, a figure that has been cited in historical literature since then.

The expulsion of the Germans from Czechoslovakia is considered a key factor in the success of the 1948 communist coup. The Communist Party controlled the distribution of seized German assets, contributing to its popularity in the border areas, where it won 75 per cent of votes in the 1946 election. Without these votes, the Communist Party would not have achieved a plurality in the Czech lands.

Mastering Austrian: A Guide to Learning the Language Efficiently

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Moravia was a part of Austria. It was a crown land of the Austrian Empire from 1804 to 1867 and was briefly a crown land of the Cisleithanian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1867 to 1918.

After World War I, Moravia became a province of the newly formed state of Czechoslovakia in 1918. Although it was annexed by Germany before World War II, it was restored to Czechoslovakia after the war. On January 1, 1949, the Czechoslovak government dissolved Moravia into several smaller administrative units.

The Moravian people are considerably aware of their Moravian identity and there is some rivalry between them and the Czechs from Bohemia. However, by nationality or ethnicity, most Moravian Slavs recognize themselves as Czechs.