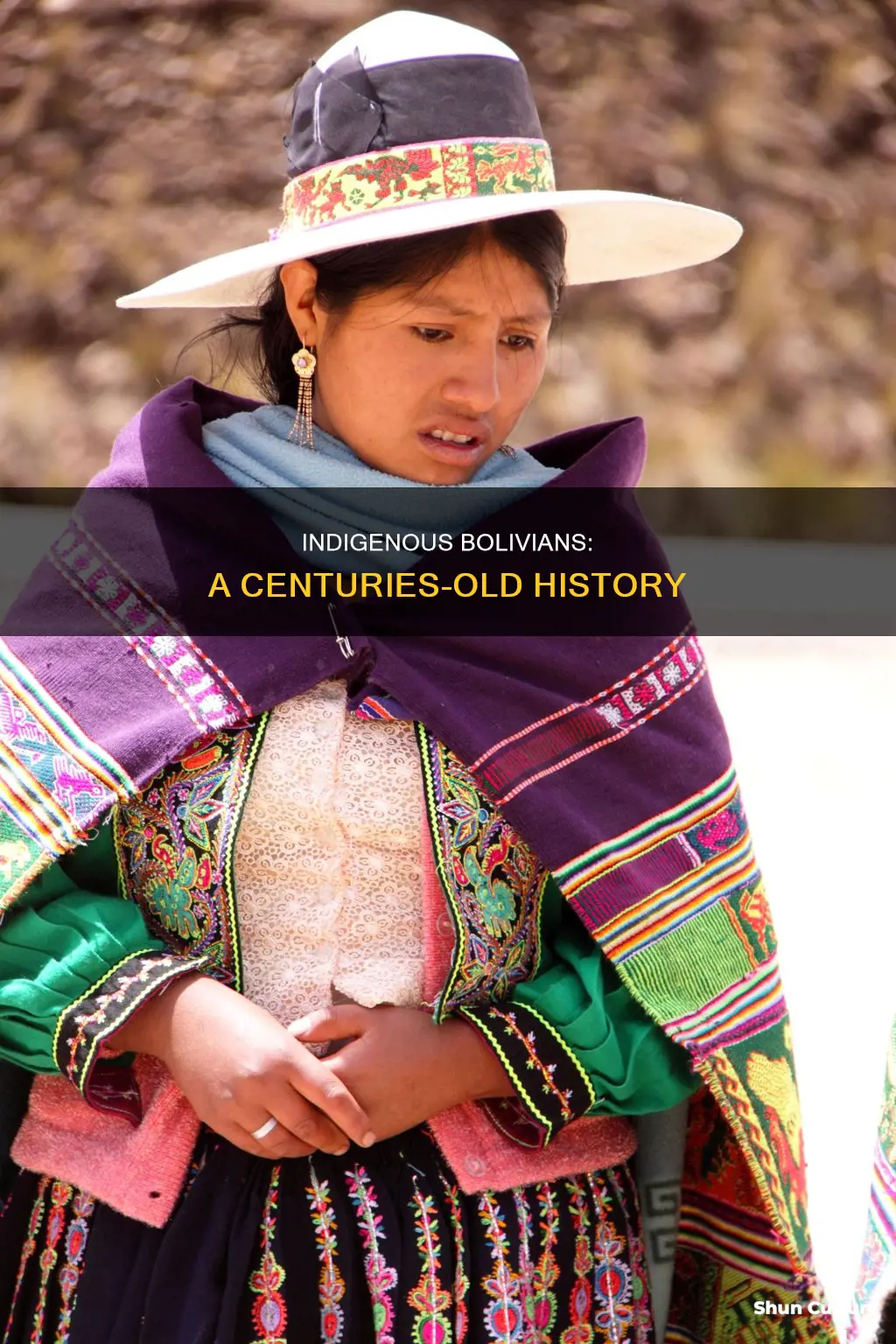

Indigenous peoples in Bolivia, or Native Bolivians, are Bolivian people of indigenous ancestry. They constitute anywhere from 20 to 60% of Bolivia's population of 11,306,341, depending on different estimates. The largest groups are the Aymara and Quechua, who are mainly located in the Andes. The geography of Bolivia includes the Andes, the Gran Chaco, and the Amazon Rainforest.

Indigenous peoples had inhabited territories spanning what is now Bolivia for thousands of years before the arrival of Spanish forces in the early 16th century.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of recognized peoples in Bolivia | 36 |

| Percentage of the Bolivian population over the age of 15 who are of Indigenous origin | 41% (2012 National Census), 48% (2017 projections) |

| Number of official languages of Bolivia | 37 |

| Number of indigenous languages of Bolivia | 36 |

| Number of Amerindian groups | 2 |

| Number of European groups | 1 |

| Number of Afro-Bolivians | 23,300 (2012 census) |

| Number of Asian groups | 2 |

What You'll Learn

The Indigenous population in Bolivia

Indigenous peoples in Bolivia, or Native Bolivians, are Bolivian people who are of indigenous ancestry. They constitute anywhere from 20 to 60% of Bolivia's population of 11,306,341, depending on different estimates. The majority of the population identify as mestizo, with mixed European and indigenous ancestry.

There are 36 recognised indigenous peoples in Bolivia, including the Aymara and Quechua (the largest communities in the western Andes) as well as Chiquitano, Guaraní and Moxeño, who make up the most numerous communities in the lowlands. The 2012 census recorded a significant drop in the proportion of the population who identified as indigenous – from 66.4% of those aged 15 or over in the 2001 census to 41% in 2012.

Highland Quechua (1.8 million) and Aymara (1.7 million) make up around half of the country’s total indigenous population. Lowland peoples include the Chiquitano, Guaraní Moxeño, Ese Eja and Ayoreo.

Indigenous peoples in Bolivia have historically suffered many years of marginalization and a lack of representation. However, the late twentieth century saw a surge of political and social mobilization in Indigenous communities. The 1952 Bolivian National Revolution liberated Bolivians and gave Indigenous peoples citizenship, but it wasn't until the 1960s and 1970s that social movements began to include Indigenous concerns. The Katarista movement, consisting of the Aymara communities of La Paz and the Altiplano, attempted to mobilize the Indigenous community and pursue an Indigenous political identity through mainstream politics. Although the Katarista movement failed to create a national political party, it influenced many peasant unions.

In the 1990s, President Sánchez de Lozada passed reforms to acknowledge Indigenous rights in Bolivian culture and society. However, many of these reforms fell short as the government continued to pass destructive environmental and anti-indigenous rules and regulations. In 1993, the Law of Constitutional Reform recognized Indigenous rights and in 1994, the Law of Popular Participation decentralized political structures, giving municipal and local governments more political autonomy. Two years later, the 1996 Electoral Law expanded Indigenous political rights as the national congress transitioned into a hybrid proportional system, increasing the number of Indigenous representatives.

In 2005, Evo Morales was elected as the country's first indigenous president. Morales attempted to establish a plurinational and postcolonial state to expand the collective rights of the indigenous community. The 2009 constitution recognized the presence of the different communities that reside in Bolivia and gave Indigenous peoples the right of self-governance and autonomy over their ancestral territories. In 2015, Bolivians elected the first Indigenous president of the Supreme Court of Justice, Justice Pastor Cristina Mamani, a lawyer from the Bolivian highlands and the Aymara community.

Despite these advances, many Indigenous communities in Bolivia continue to face challenges, particularly in relation to the country's extractive industries. A highly contentious issue is a proposed road across the Isiboro-Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS) in the Bolivian Amazon, which would cut through the protected indigenous homeland of the Chimáne, Yuracaré and Moxeño-Trinitario peoples. In 2011, an estimated 1,000 mainly indigenous residents of the TIPNIS set off on a 360-mile trek to La Paz in protest, but the march was violently suppressed by police. In 2017, Morales reversed his stance and signed a law rescinding the protection of the TIPNIS, angering local indigenous activists.

Bolivia's Refugee Crisis: Who Seeks Asylum?

You may want to see also

The history of Native Americans in the United States

Pre-Columbian Era

Native Americans, or Indigenous Americans, have lived in the Americas for tens of thousands of years, with the first migrations from Eurasia to the Americas occurring via the Bering land bridge. Over time, these early migrants spread throughout the Americas, diversifying into hundreds of distinct nations and tribes. The archaeological record in the Americas has been divided into several periods, including the Paleo-Indian or Lithic stage, which lasted until about 5000/3000 BCE, and the Archaic period, which lasted until about 1000 BCE.

European Colonization

The arrival of European colonists in the Americas beginning in 1492 had a devastating impact on Native American populations. Diseases introduced by the colonists, such as smallpox, as well as warfare, ethnic cleansing, enslavement, and forced removal from their ancestral lands, led to a precipitous decline in the Native American population. The European settlers also waged war and perpetrated massacres against Native American peoples and subjected them to discriminatory government policies and forced assimilation.

Post-Columbian Era

Into the 20th century, Native Americans continued to face oppression and injustice. They were often forced to relocate to reservations, far from their ancestral lands. Despite these challenges, Native Americans have fought for their rights and worked to preserve their cultures and traditions. The Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968, for example, gave tribal members protections against abuses by tribal governments.

Contemporary Times

Today, there are over five million Native Americans in the United States, with the majority living outside reservations. They continue to face contemporary issues such as poverty, discrimination, and lack of economic opportunities. However, there have also been positive developments, including the rise of Native American activism and the establishment of independent Native American media outlets and educational institutions. Native Americans now have all the rights guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution and can vote in elections and run for political office.

Bolivia's Military Might: A Comprehensive Overview

You may want to see also

The arrival of Spanish forces in the early 16th century

Indigenous peoples have inhabited territories spanning what is now Bolivia for thousands of years. By the time of the arrival of Spanish forces in the early 16th century, the Inca Empire was ascendant, though severely weakened by internal fighting.

In 1524, Francisco Pizarro and his fellow conquistadors from the rapidly growing Spanish Empire first arrived in the New World. Pizarro enjoyed stunning successes in his military campaign against the Incas, who were defeated despite some resistance. In 1538, the Spaniards defeated Inca forces near Lake Titicaca, allowing Spanish penetration into central and southern Bolivia.

During the first two decades of Spanish rule, the settlement of the Bolivian highlands—then known as Upper (Alto) Peru or Charcas—was delayed by a civil war between the forces of Pizarro and Diego de Almagro. The two conquistadors had divided the Inca territory, with the north under the control of Pizarro and the south under that of Almagro. Fighting broke out in 1537 when Almagro seized Cuzco after suppressing the Manco Inca rebellion. Pizarro defeated and executed Almagro in 1538, following the Battle of Las Salinas, but was himself assassinated three years later by former supporters of Almagro.

Pizarro's brother Gonzalo assumed control of Upper Peru but soon became embroiled in a rebellion against the Spanish crown. Only with the execution of Gonzalo Pizarro in 1548 did Spain succeed in reasserting its authority. That year, colonial authorities established the city of La Paz, which soon became an important commercial and transshipment center.

Indian resistance delayed the conquest and settlement of the Bolivian lowlands. The Spanish established Santa Cruz de la Sierra in 1561, but the Gran Chaco, the colonial name for the arid Chaco region, remained a violent frontier throughout the colonial period. In the Chaco, the Indians, mostly Chiriguano, carried out relentless attacks on colonial settlements and remained independent of direct Spanish control.

In the region then known as Upper Peru, the Spaniards found the mineral treasure chest they had been searching for—Potosí had the Western world's largest concentration of silver. At its height in the 16th century, Potosí supported a population of more than 150,000, making it the world's largest urban center. In the 1570s, Viceroy Francisco de Toledo introduced a coercive form of labor, the mita, which required native males from highland districts to spend every sixth year working in the mines. The mita and technological advances in refining caused mining at Potosí to flourish.

Bolivia's Economy: Size and Scope Explored

You may want to see also

The 1952 Bolivian National Revolution

The origins of the revolution can be traced back to the Great Depression and Bolivia's defeat in the Chaco War (1932-1935). These events weakened the mining industry and led to state intervention in the economy, as well as a questioning of the existing political and social model. During the 1920s, the nationalist government of Hernando Siles Reyes attempted to address some fundamental socioeconomic issues, and these measures were deepened in the following decade by the military governments of Germán Busch and David Toro, influenced by European nationalism.

The Chaco War resulted in widespread dissatisfaction among the working class and farmers, as well as a loss of life and territory that discredited the traditional ruling classes. It also sparked political awareness among the indigenous people, who made up a significant portion of the army. From the end of the Chaco War until the 1952 revolution, the emergence of contending ideologies and the demands of new groups dominated Bolivian politics.

The MNR emerged as a broadly-based party in opposition to the status quo. After being denied victory in the 1951 presidential elections, the party led a successful revolution against the government in 1952. The revolution began with a hunger march through La Paz that attracted most sectors of society. The Bolivian military was severely demoralized, and the MNR seized arsenals and distributed arms to civilians. Armed miners marched on La Paz, blocking troops attempting to reinforce the city. After three days of fighting, the desertion of General Antonio Seleme, and the loss of 600 lives, the army surrendered. Víctor Paz Estenssoro assumed the presidency on 16 April 1952.

The new government quickly established universal suffrage, granting the right to vote to the illiterate, indigenous peoples, and women. This was a radical measure in the Latin American context. The government also moved to control the armed forces, purging officers associated with past Conservative Party regimes and reducing the size and budget of the military. In addition, the MNR implemented land reforms, redistributing land from hacienda owners to indigenous farming communities.

While the 1952 Bolivian National Revolution brought about significant political change, including greater inclusion of indigenous Aymara and Quechua farmers, it fell short of addressing the marginalization faced by indigenous communities. Social movements such as the Katarista movement in the 1960s and 1970s sought to pursue an indigenous political identity and increase indigenous representation in mainstream politics and life. However, it was not until the late twentieth century that there was a surge of political and social mobilization among indigenous communities, leading to further reforms and recognition of indigenous rights in Bolivia.

The Giant Bolivian Habanero: How Big Does It Grow?

You may want to see also

The election of Evo Morales

Morales won the 2005 election with 53.7% of the vote, becoming the first president in Bolivia to win with an absolute majority in 40 years. His victory was widely celebrated among the indigenous people in the Americas, particularly in Bolivia, where around 62% of the population identified as indigenous at the time.

During his first term, Morales emphasized nationalism, anti-imperialism, and anti-neoliberalism. He reduced his presidential wage and that of his ministers by 57% and urged members of Congress to do the same. Morales' government experienced unprecedented economic strength, maintaining one of the world's highest levels of economic growth during the global financial crisis of 2007-2008. His administration also oversaw strong economic growth, poverty reduction, and increased investment in schools, hospitals, and infrastructure.

Morales' first term also saw the approval of a new constitution in a national referendum in January 2009. The new constitution emphasized Bolivian sovereignty over natural resources, separated church and state, forbade foreign military bases in the country, implemented a two-term limit for the presidency, and permitted limited regional autonomy.

Morales was re-elected in 2009 with a landslide majority, polling 64.2% of the vote. During his second term, he began to speak openly of "communitarian socialism" as the ideology he desired for Bolivia's future.

In 2014, Morales became the oldest active professional soccer player in the world after signing a contract with Sport Boys Warnes.

Morales' third term as president was marked by controversy and unrest. He had initially stated that he would not run for re-election in 2014, but a ruling by the Plurinational Constitutional Court allowed him to run for a third term. Morales won the 2014 election, but his refusal to accept the results of a 2016 referendum on term limits, which he lost, sparked protests.

In the 2019 election, Morales garnered about 45% of the vote, with his main opponent, Carlos Mesa, receiving around 38%. However, there was a delay in announcing the results, and when it was announced that Morales had extended his margin of victory to just over 10%, avoiding a runoff, the response was swift and violent. Accusations of fraud escalated, and the country was paralyzed by widespread protests and strikes.

On November 10, 2019, Morales resigned from the presidency, insisting that there had been no wrongdoing and claiming that he was the victim of a coup.

Exploring Bolivia's Natural Legacy: A Wealth of National Parks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

American Indians have inhabited territories in Bolivia for thousands of years, with evidence of pre-Columbian cultures dating back to 300-1000 AD.

There are 36 recognized American Indian groups in Bolivia, including the Quechua, Aymara, Chiquitano, Guaraní, and Moxeño.

The main languages spoken by American Indians in Bolivia are Spanish, Quechua, and Aymara. However, there are also 34 other indigenous languages recognized in the country.

According to the 2012 census, 41% of the Bolivian population over the age of 15 is of indigenous origin. However, this number is estimated to have increased to 48% in 2017.

One major challenge is the exploration for oil and gas reserves, as well as hydroelectric projects, which directly impact the territories inhabited by American Indian communities.