Bolivia is a multiethnic and multilingual society, with a population made up of various ethnic, religious, and national origins. The majority of the population is comprised of indigenous people and Old World immigrants and their descendants. While the exact number of women in Bolivia who identify as indigenous is unclear, according to the 2012 Population and Housing Census, over 40% of people in Bolivia identify as indigenous or Afro-descendants. Indigenous women in Bolivia face a higher risk of exclusion and discrimination.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Percentage of Bolivian population over the age of 15 who are of Indigenous origin | 41% (2012 National Census); 48% (2017 projection) |

| Number of recognised Indigenous peoples in Bolivia | 36 |

| Percentage of Indigenous women who feel discriminated against | 20% |

| Percentage of non-Indigenous women who feel discriminated against | 14% |

| Percentage of Indigenous women in urban Bolivia who are likely to finish secondary school compared to a non-Indigenous male student | 50% |

| Percentage of Indigenous rural women who are likely to finish secondary school compared to a non-Indigenous urban man | 20% |

What You'll Learn

- Indigenous women face a higher risk of exclusion and discrimination

- Urbanization has played a role in the reduced proportion of Bolivians identifying as indigenous

- Indigenous women are five times less likely to complete secondary school than non-indigenous urban men

- Indigenous women are less likely to have a doctor or nurse present when giving birth

- Indigenous women are more likely to experience discrimination in academic environments

Indigenous women face a higher risk of exclusion and discrimination

Indigenous women in Bolivia face a higher risk of exclusion and discrimination. They are confronted with multiple layers of discrimination and structural barriers that lead to mutually reinforcing human rights abuses. Sexism, racism, economic status, and structural and institutional inequities resulting from colonization and globalization make indigenous women more vulnerable to human rights abuses.

Indigenous women in Bolivia are specifically and disproportionately impacted by a lack of legal recognition within national legislative frameworks. They are denied basic social services, freedom of movement and speech, and land ownership. This enhances their vulnerability to exploitation and violence by state and non-state actors.

Discrimination against indigenous women and girls is prevalent and is a form of violence itself. It is a cause of the violence faced by indigenous women and girls, and a cause of the impunity and complacency with which this violence is treated by public officials. Dismissive responses from authorities, often based on discriminatory and stereotyped beliefs, perpetuate and enhance these beliefs and perceptions of indigenous women and girls in society, making them vulnerable to further violence.

Indigenous women and girls in Bolivia experience diverse forms of violence, in disproportionate amounts, as compared to other women and girls. This includes a higher exposure to various forms of sexual violence, trafficking, and domestic violence. They are also significantly more likely to be victims of different forms of sexual violence and to experience rape than non-indigenous women and girls.

Indigenous women in Bolivia are also discriminated against and face violence in the exercise of their economic, social, and cultural rights. They are at higher risk of sexual violence when traveling to and from school or when they move away from their communities to study due to the remoteness of many indigenous communities and the long distances they need to travel to attend school.

Obstetric violence against indigenous women is also a widespread practice in Bolivia. Common reports include practices such as forcing indigenous women to give birth in a supine position rather than their preferred vertical position, banning traditional midwifery, and criminalizing traditional practices.

Indigenous women in Bolivia are also excluded from access to and ownership of land. The appropriation of indigenous traditional lands has specific gendered effects, as women and girls are the keepers of traditions and culture in their communities. Land appropriation infringes on indigenous women and girls' ability to pursue traditional occupations, generate income, maintain cultures and ways of life, and erodes indigenous women's authority within their communities.

Indigenous women in Bolivia are also underrepresented in national parliaments, local governments, and the judiciary. They encounter barriers to their participation in decision-making in their own communities, with gender stereotyping as the cause.

Overall, indigenous women in Bolivia face a range of challenges and risks of exclusion and discrimination due to their gender and ethnicity. These factors create specific types of human rights abuses and require an intersectional approach to address their human rights situation effectively.

Exploring the Heights of Cochabamba, Bolivia

You may want to see also

Urbanization has played a role in the reduced proportion of Bolivians identifying as indigenous

The proportion of Bolivians identifying as indigenous has decreased in recent years. While the 2001 census recorded 62% of Bolivians aged 15 and over self-identifying as indigenous, this number fell to 41% in the 2012 census. Urbanization has played a role in this reduction.

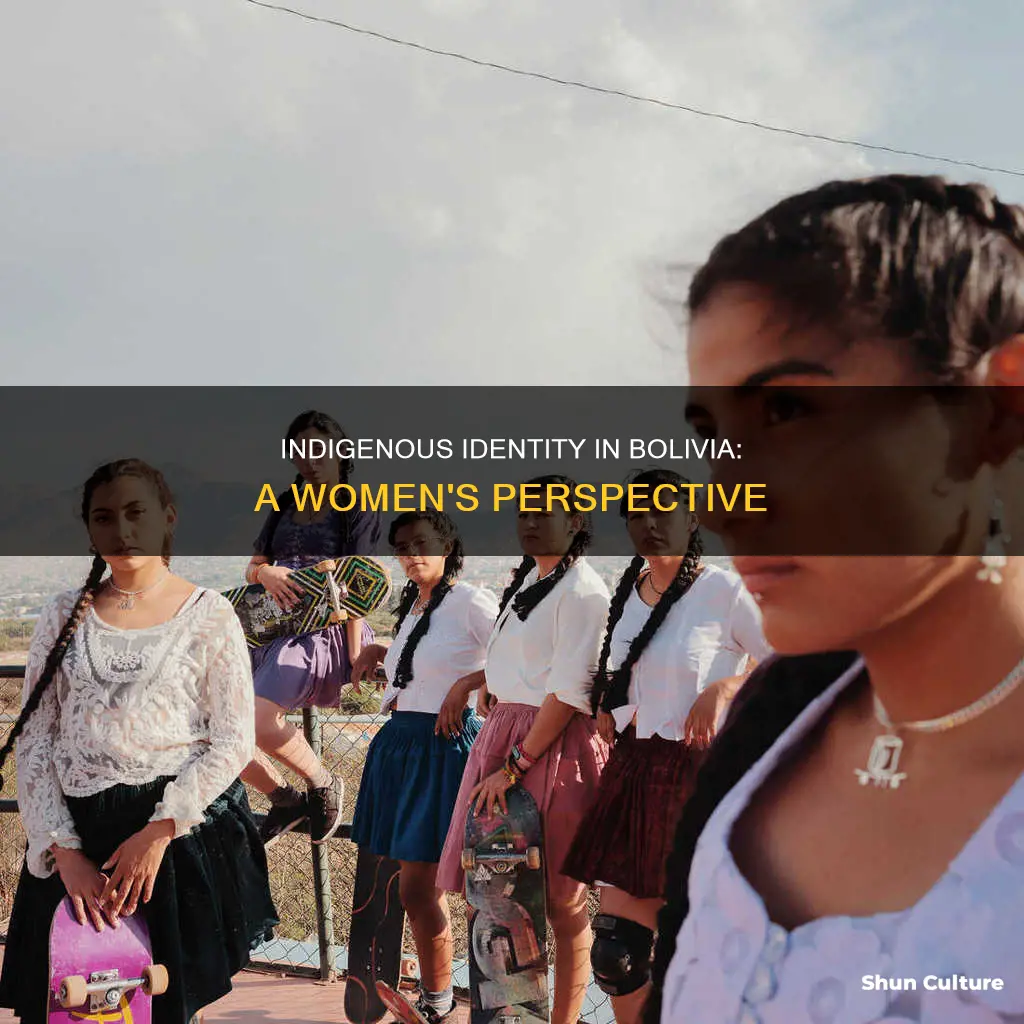

Indigenous identity in Bolivia is strongly tied to conceptions of the rural 'campesino' (peasant). As more Bolivians move to urban areas, they are less likely to self-identify with a specific indigenous group. This trend is particularly notable among the younger generation, who are more likely to be influenced by urban culture and less likely to speak an indigenous language.

In recent decades, increasing numbers of indigenous women have migrated to urban areas. Living on the outskirts of cities like La Paz, they often work as domestic workers or street vendors. Despite facing discrimination due to their distinct dress and cultural traditions, indigenous women in urban areas have made significant strides in political participation and empowerment. They are increasingly represented in the media, government ministries, banks, and law offices.

Urbanization has also provided opportunities for indigenous communities to redefine their identity. For example, some urban residents with indigenous ancestry may choose to identify as indigenous for political reasons, such as expressing solidarity with indigenous movements or advocating for land rights and environmental protection. Additionally, international agencies like the ILO, UN, and World Bank emphasize the importance of self-identification for indigenous people.

While urbanization has contributed to the reduced proportion of Bolivians identifying as indigenous, it is essential to consider other factors as well. The improvement in the situation of marginalized indigenous communities under the leadership of Evo Morales, Bolivia's first indigenous president, may also play a role. Additionally, the 2012 census may not fully capture the complexity of indigenous identity, as some Bolivians may have indigenous ancestry but do not self-identify as indigenous due to various social and cultural factors.

Bolivia Visa: Drop Off Application In-Person?

You may want to see also

Indigenous women are five times less likely to complete secondary school than non-indigenous urban men

According to the 2012 National Census, 41% of the Bolivian population over the age of 15 is of Indigenous origin, although 2017 projections from the National Institute of Statistics (INE) indicate that this percentage is likely to have now increased to 48%. Of the 36 recognized peoples in the country, the majority live in the Andes and are Quechua- or Aymara-speaking (49.5% and 40.6% respectively) and they self-identify as one of 16 nationalities.

Indigenous women in Bolivia face unique challenges when it comes to accessing education. They are five times less likely to complete secondary school than non-indigenous urban men. This disparity is due to a variety of factors, including financial and geographical constraints, as well as cultural and social barriers.

Financial constraints play a significant role in limiting educational opportunities for Indigenous women. They are more likely to come from low-income households, which have been associated with lower levels of educational attainment. Additionally, the cost of commuting to larger urban centres where schools are located can be a burden for Indigenous women, further hindering their access to education.

Geographical constraints also present a challenge. Indigenous communities tend to be located in rural and remote areas, which often lack essential services such as educational facilities. This remoteness can make it difficult for Indigenous women to access schools and complete their secondary education.

Cultural and social barriers further contribute to the gap in educational attainment. Indigenous identity in Bolivia is strongly tied to conceptions of the rural "campesino" (peasant), and urbanisation may have played a role in the reduced proportion of Bolivians identifying as indigenous. Additionally, Indigenous women who migrate to urban areas often face discrimination and are singled out for their traditional dress. This discrimination can create a hostile environment and deter Indigenous women from pursuing their education.

To address these disparities, it is crucial to implement targeted interventions that address the specific challenges faced by Indigenous women. This may include providing financial support to improve access to education, ensuring that educational facilities are available in remote areas, and promoting cultural sensitivity and inclusion in schools to create a welcoming environment for Indigenous students.

Furthermore, it is important to recognise the resilience and agency of Indigenous women in Bolivia. Despite the obstacles they face, many have migrated to urban areas, pursued education, and found employment in various sectors. Their voices are increasingly being heard in national media, and they are occupying positions of influence in journalism, television, government ministries, banks, and law offices.

Bolivia's Economy: Market or Non-Market?

You may want to see also

Indigenous women are less likely to have a doctor or nurse present when giving birth

According to the 2012 National Census, 41% of the Bolivian population over the age of 15 are of Indigenous origin, although the National Institute of Statistics’ (INE) 2017 projections indicate that this percentage is likely to have increased to 48%. There are 36 recognized Indigenous peoples in Bolivia, with the majority in the Andes being Quechua-speaking peoples (49.5%) and Aymara (40.6%), who self-identify as 16 nations.

Indigenous women in Bolivia have historically been marginalized and underrepresented. They have also been subjected to violence, human trafficking, prostitution, and alcoholism due to the domination of men in communities with a high number of male migrant workers.

Indigenous women in Bolivia are less likely to have a doctor or nurse present when giving birth due to various factors. Firstly, there is a shortage of medical professionals in rural and remote communities, which leads to Indigenous women having to travel to urban centers for childbirth. This separation from their support networks can cause unnecessary stress and negatively impact their health. Secondly, institutional factors such as long waiting times and multiple points of contact with different health professionals can be overwhelming and exhausting for Indigenous women, especially those who are not familiar with the bureaucracies of large hospitals. Thirdly, cultural differences in communication styles and medical beliefs between Indigenous women and non-Indigenous health care providers can lead to misunderstandings and mistrust. For example, Indigenous women's nonverbal communication style, such as shrugging their shoulders or giving short answers, may be misinterpreted as non-compliance or rudeness by health care providers.

To improve the quality of patient-provider interactions and address the disparities in perinatal health between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, it is essential to provide training for medical professionals in delivering culturally safe care and addressing bureaucratic constraints. Increasing the number of Indigenous health care providers and incorporating Indigenous knowledge and practices into clinical practice can also help to reduce the stress and cultural isolation experienced by Indigenous women during childbirth.

Exploring Bolivia: Entry Rules for American Travelers

You may want to see also

Indigenous women are more likely to experience discrimination in academic environments

According to the 2012 National Census, 41% of the Bolivian population over the age of 15 is of Indigenous origin. However, the National Institute of Statistics' (INE) 2017 projections indicate that this percentage is likely to have increased to 48%. There are 36 recognised Indigenous Peoples in Bolivia, the majority of whom live in the Andes and are Quechua- or Aymara-speaking (49.5% and 40.6% respectively) and they self-identify as one of 16 nationalities.

Indigenous women in Bolivia face discrimination in academic environments. This is due in part to the fact that, in Bolivia, Indigenous identity is strongly tied to conceptions of the rural 'campesino' (peasant). As a result, the urbanization and modernization of the country has led to a decline in the number of Bolivians identifying as Indigenous. This has contributed to the discrimination faced by Indigenous women in academic environments, as their identity is often not respected or understood by their non-Indigenous peers.

Furthermore, the education system in Bolivia often does not provide resources or support for Indigenous cultures and languages. There are too few teachers who speak Indigenous languages, and educational materials that provide accurate and fair information on Indigenous peoples and their ways of life are rare. This lack of representation and support for Indigenous cultures in the education system can create a hostile environment for Indigenous women, who may experience discrimination and bullying as a result.

In addition, Indigenous women in Bolivia have traditionally been marginalized and underrepresented in society and politics. While there have been some improvements in recent years, with the election of the country's first Indigenous president, Evo Morales, and the creation of the first Indigenous-led conservation efforts, Indigenous women still face barriers to participation and leadership in academic environments.

Moreover, Indigenous women in Bolivia face intersecting forms of discrimination, including racism and sexism. This can lead to further alienation and trauma, as they navigate spaces that are not always welcoming or inclusive of their identities and experiences.

Finally, the specific challenges faced by Indigenous women in academic environments are often overlooked or underestimated. There is a lack of research and data on the unique experiences and perspectives of Indigenous women in these contexts, which can contribute to a cycle of invisibility and exclusion.

Exploring the Diverse National Identity of Bolivia

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

According to the 2012 Population and Housing Census, more than 40% of people in Bolivia identify as indigenous. While this includes men and women, we can assume that a significant portion of this percentage is made up of women.

Urban indigenous women in Bolivia are about half as likely to finish secondary school compared to non-indigenous male students. In rural areas, an indigenous woman is five times less likely to complete secondary school than her non-indigenous, urban counterpart.

Indigenous women in Bolivia face multiple disadvantages due to the intersection of their gender and ethnicity. They are at a higher risk of exclusion and discrimination in various aspects of their lives, including education and health services.

In recent decades, increasing numbers of indigenous women have migrated to urban areas, which has provided opportunities for them to redefine their identity and gain political participation and empowerment. They are now occupying positions in media, government ministries, banks, and law offices.