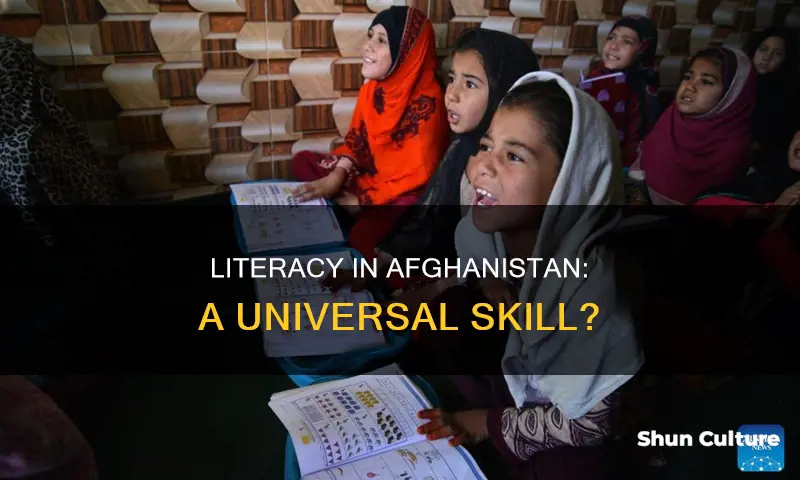

Afghanistan is a country in Central Asia with a population of around 27 million people. Decades of conflict and restrictions on education have resulted in a literacy crisis, with less than half of the population over the age of 15 able to read and write. This issue disproportionately affects women, with only 15% of Afghan women considered literate compared to 47% of men.

Although there has been a significant increase in school enrolment over the past two decades, with the number of students rising from 1 million to 9.5 million, many Afghan children still lack basic literacy skills. Data suggests that 93% of late primary-age children in Afghanistan are not proficient in reading.

The lack of access to quality education, particularly for girls, remains a pressing concern in Afghanistan. Despite assurances from the Taliban that they will respect the right to education, there are fears that restrictions on girls' education may be reimposed.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Literacy rate of Afghan population over the age of 15 | Less than 50% |

| Literacy rate of Afghan women | 15% |

| Literacy rate of Afghan men | 47% |

| Number of Afghan children enrolled in school | 9.5 million |

| Percentage of late primary age children in Afghanistan who are not proficient in reading | 93% |

| Percentage of population under 15 years of age | 42.5% |

What You'll Learn

- The literacy rate in Afghanistan is low, with less than half of the population over 15 being able to read and write

- The Taliban banned girls from attending school and women from working outside the home

- The World Bank defines Afghanistan's literacy crisis as learning poverty, which is 35.2% higher than the average for the South Asia region

- Literacy is a tool that can help people unlock opportunities for work, improved health and well-being

- Literacy rates among Afghan women are especially low, with only 15% of women being able to read and write

The literacy rate in Afghanistan is low, with less than half of the population over 15 being able to read and write

Afghanistan is a country in Central Asia with a population of nearly 27 million people. Decades of conflict and restrictions on education have resulted in a low literacy rate, with less than half of the population over the age of 15 being able to read and write. This issue is particularly pronounced among women, who have historically faced significant barriers to accessing education.

During the Taliban's rule, which began in 1996, girls and women were prohibited from attending school and working outside the home. They were also subject to strict rules that restricted their movement and required them to wear a burqa in public. These measures had a devastating impact on women's access to education, causing the gender gap in literacy to widen. According to UNICEF, 47% of Afghan men can read and write, compared to only 15% of women.

Despite these challenges, there have been some improvements in recent years. Over the past two decades, there has been a significant increase in the number of Afghan children enrolled in school, rising from 1 million to 9.5 million students. However, data suggests that 93% of late primary-age children in Afghanistan are not proficient in reading. This issue, referred to as "learning poverty" by the World Bank, is a pressing concern in the country, where 42.5% of the population is under the age of 15.

The low literacy rate in Afghanistan has far-reaching consequences. As highlighted by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, literacy is "a bulwark against poverty and a building block for development." It unlocks opportunities for work, improved health, and participation in society. Therefore, it is crucial that Afghanistan's leaders uphold the right to education and that the international community provides coordinated support to protect learning for all Afghan children.

The Fragile Stability: Navigating Afghanistan's Macropolitical Landscape

You may want to see also

The Taliban banned girls from attending school and women from working outside the home

In Afghanistan, the Taliban's ban on girls attending school and women working outside the home has had a devastating impact on the lives of women and girls, as well as the country's economy and social fabric. The ban has excluded women from public life and denied them access to education and employment, limiting their ability to contribute to Afghanistan's future.

The Taliban first prohibited girls and women from attending school and working outside the home when they previously ruled Afghanistan in the late 1990s. After regaining control of the country in 2021, they initially promised to respect girls' right to education. However, in March 2022, the Taliban barred girls from attending school beyond the sixth grade, with similar restrictions later imposed on female university students and lecturers. The Taliban have also targeted girls' and boys' schools, with several being burned down in recent attacks.

As a result of the ban, girls and women in Afghanistan have been deprived of their basic rights and access to education and employment. This has led to increased rates of depression, anxiety, and even suicidal thoughts among girls and women, with some turning to narcotics as a means of escape. The ban has also disrupted the pipeline of educated women entering sectors such as healthcare, threatening the availability of basic healthcare services for Afghan women and children. Furthermore, the loss of jobs in the education sector and the exclusion of women from the job market have hurt the country's GDP, exacerbating Afghanistan's economic woes.

The Taliban's interpretation of Islamic law, or Sharia, is cited as the primary reason for the ban on girls' education. However, this interpretation has been widely criticized and contradicts the views of clerics outside Afghanistan, who emphasize the equal emphasis Islam places on female and male education. Despite international condemnation and the Taliban's desire for international recognition, they have shown no signs of reversing their decision, prioritizing their interpretation of Sharia over basic literacy and numeracy for Afghanistan's children.

US Troops and Afghanistan's Opium Fields: A Complex Relationship

You may want to see also

The World Bank defines Afghanistan's literacy crisis as learning poverty, which is 35.2% higher than the average for the South Asia region

Afghanistan has a literacy crisis. The country's literacy rate for 2022 was 0%, a 37.27% decline from 2021. In 2021, the literacy rate was 37.27%, a 37.27% increase from 2020.

The World Bank defines this crisis as "learning poverty", referring to children being unable to read and understand a simple text by the age of 10. Learning poverty is 35.2% higher in Afghanistan than the average for the South Asia region and 3.6% higher than the average for low-income countries.

The literacy rate among the population aged 15 and older was just 28% in 2000. By 2010, it had risen to 31.4%, and by 2018, 43% of Afghans were able to read and write. However, the current literacy rates reflect a disparity between the genders: only 37% of teenage girls can read and write, compared to 66% of adolescent boys.

The gap in male-female literacy in Afghanistan is striking. While the inequalities in education are significant within South Asia as a whole, the situation in Afghanistan is especially dramatic. Within South Asia, 1.75 times as many men as women can read and write. In Afghanistan, more than three times as many men as women are literate. Some 47% of Afghan men and a tiny 15% of women can read and write, according to the UN Children's Fund (UNICEF).

The global literacy rate for all people aged 15 and above is 86.3%. The global literacy rate for all males is 90.0%, and the rate for all females is 82.7%. The rate varies throughout the world, with developed nations having a rate of 99.2% (2013), South and West Asia having 70.2% (2015), and sub-Saharan Africa at 64.0% (2015). Over 75% of the world's 781 million illiterate adults are found in South Asia, West Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, and women represent almost two-thirds of all illiterate adults globally.

The Afghan Conundrum: Assessing Terrorism Threats Post-War

You may want to see also

Literacy is a tool that can help people unlock opportunities for work, improved health and well-being

Literacy is a powerful tool that can help people unlock opportunities for work, improved health and well-being. In Afghanistan, less than half of the population over the age of 15 can read and write. This is due to decades of conflict and restrictions on education, which have disproportionately affected women and girls.

Literacy is a fundamental skill that can transform lives and break cycles of poverty. Illiterate people are more likely to be unemployed, face exploitation, and suffer from poor health. They are also less likely to be aware of their human rights and how to protect themselves from abuse.

Literacy empowers individuals to understand and assert their rights, improving their ability to access healthcare, earn a living, and make informed decisions about their lives. It is also linked to improved gender equality, as literate women tend to have higher incomes and better knowledge of HIV prevention.

Furthermore, literacy can contribute to peacebuilding and post-conflict recovery. In Afghanistan, for example, women like Khalida have enrolled in literacy courses, gaining the skills and confidence to serve their communities and start their own businesses. Literacy enables people to actively participate in society and access information, which is especially important in countries transitioning from autocracy to democracy or recovering from conflict.

However, it is important to recognize that simply attending school does not guarantee literacy. The quality of education is crucial, and in Afghanistan, 93% of late primary-age children are not proficient in reading. This crisis, known as "learning poverty," underscores the need for coordinated international efforts to improve access to quality education and address gender disparities in Afghanistan.

By investing in education and literacy, we can unlock opportunities and improve the well-being of individuals, families, and communities, contributing to sustainable development and a more peaceful future.

The Surprising Similarities Between Afghanistan and Massachusetts: A Tale of Two Distant Lands

You may want to see also

Literacy rates among Afghan women are especially low, with only 15% of women being able to read and write

Afghanistan has one of the lowest literacy rates in the world, with only 43% of the population being literate as of 2018. The gap between male and female literacy is especially stark, with 47% of men and only 15% of women able to read and write. This disparity has worsened over time, growing from 27 percentage points in the 1980s to 32 percentage points in the 1990s.

The low literacy rate among Afghan women is a result of several factors, including cultural norms, lack of educational infrastructure, and conflict. Traditional gender norms and a patriarchal culture in Afghanistan have long reinforced discrimination against women and girls, limiting their access to education. In rural areas, women face even more challenges due to entrenched gender norms and a lack of available services. The Taliban, a religious-based movement that took power in 1996, has also played a significant role in restricting women's access to education. One of the first edicts issued by the Taliban regime was to prohibit girls and women from attending school.

The conflict and instability in Afghanistan over the past four decades have also taken a toll on the country's education system, depriving millions of Afghans, especially women and girls, of literacy and learning opportunities. The recent escalation of the conflict and the near collapse of the health system due to frozen funds have further exacerbated the situation. Additionally, the lack of female teachers, particularly in remote areas, and the low priority given to education in the national budget have hindered progress in improving literacy rates among women.

Despite these challenges, there have been some improvements in female literacy rates over the years. According to a 2023 UNESCO report, the female literacy rate in Afghanistan almost doubled from 17% in 2011 to 30% in 2018. However, there is still a long way to go to achieve gender parity in literacy and ensure that all Afghans, especially women and girls, have access to education.

A Nation in Need: Afghanistan's Refugee Camp Crisis

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Less than half of the population over the age of 15 in Afghanistan are literate.

In the 1980s, the literacy rate among males was 5.5 times that of females. In the 1990s, this gap widened to men being literate three times more than women.

Decades of conflict and restrictions on the provision of education have prevented many Afghans from learning to read and write.

Illiteracy is a bulwark against poverty and a block for development. It is a tool that can unlock opportunities for work and improved health and well-being.