Brunei is split into two parts because of a series of historical events that led to the decline of the Bruneian Empire in the 19th century. The Sultanate ceded Sarawak (Kuching) to James Brooke, who became known as the White Rajah, and also ceded Sabah to the British North Borneo Chartered Company. In 1888, Brunei became a British protectorate and was assigned a British resident as colonial manager in 1906. Brunei's territory continued to shrink as the Brookes leased or annexed more land. In 1890, the Raj of Sarawak annexed Brunei's Pandaruan District, which left Brunei with its current small land mass and separation into two parts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reason for Brunei being split in two | Annexation of the district of Limbang by Sarawak's Rajah Charles Brooke in 1890 |

| Current status of Limbang | Part of the Malaysian state of Sarawak |

| Brunei's status within Borneo | Brunei is the only sovereign state on Borneo; the remainder of the island is divided between Malaysia and Indonesia |

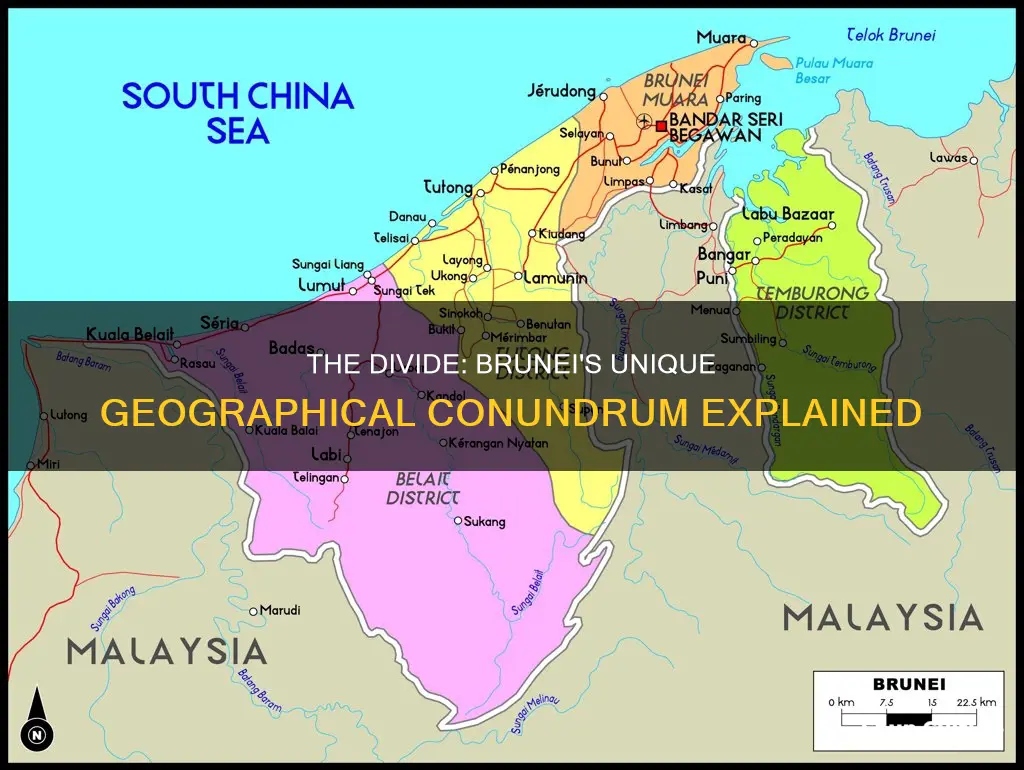

| Geography of Brunei | Consists of two unconnected parts with a total area of 5,765 square kilometres on the island of Borneo |

| Population of Brunei | Approximately 408,000 as of July 2010 |

| Demographics of Brunei | About 97% of the population lives in the larger western part, while only about 10,000 people live in the mountainous eastern part |

| Economy of Brunei | Dominated by production from major oil and natural gas fields |

What You'll Learn

The annexation of Limbang

The roots of this annexation can be traced back to the mid-19th century when the Empire of Brunei ruled much of the island of Borneo. However, its power was waning, and it faced challenges from pirates. In 1839, James Brooke, a British adventurer, offered his assistance to the Sultan of Brunei in dealing with piracy. Brooke's success led to him being given control of Sarawak, where he ruled as the "White Rajah." Over time, the Kingdom of Sarawak expanded its territory, often at the expense of Brunei.

The specific events leading to the annexation of Limbang began in 1884 with a rebellion by Limbang residents against high tax rates imposed by the Bruneian Empire. This provided an opportunity for William Hood Treacher, the governor of North Borneo and British royal consul at Labuan, to intervene. Treacher successfully mediated the dispute and leased several areas from the Sultan of Brunei, including the Padas River and Tawaran (now Tuaran).

The Brooke government, feeling threatened by Treacher's expansion, sent F.O. Maxwell to Brunei to demand compensation for the killings of Sarawak subjects in the Trusan area. Under pressure, Temenggong Hashim, the local ruler, agreed to cede the Trusan area to Sarawak. However, the Sultan of Brunei, Sultan Mumin, did not consent to this cession. Charles Brooke, who had succeeded his uncle James as the White Rajah, later occupied Trusan by force. Brunei eventually agreed to cede Trusan in 1885 and Padas in 1887.

In 1886, Leys, the former consul of Brunei, and Charles Brooke attempted to persuade Sultan Hashim to cede Limbang but were unsuccessful. Sultan Hashim considered further cession of Bruneian territory as a threat to his authority and the survival of his sultanate. Sir Frederick Weld, the former governor of the Straits Settlement, consulted the chiefs of the Limbang River, who rejected Sultan Hashim's rule and expressed a preference for rule by a white man. Weld and Crocker, the acting governor of North Borneo, pressured Sultan Hashim to accept a Resident in Limbang or face seizure of the area by James Brooke without compensation.

On March 17, 1890, Rajah Charles Brooke annexed Limbang, claiming that the local chiefs had been independent of Brunei's rule for years and had hoisted a Sarawak flag. This annexation was subject to the approval of the British government. Sultan Hashim protested against the move and asserted that the people of Limbang had been paying tribute to him, indicating Brunei's sovereignty over the area. A referendum among the headmen of Limbang was organised by Noel P. Trevenen, the British Consul General in Borneo, with most favouring Sarawak's rule. However, Sultan Hashim disputed the voting results and Trevenen's conduct during the referendum.

Despite Sultan Hashim's objections and continued protests, the British colonial office considered the case closed in August 1895, without reaching an agreement with the Sultan or the Brooke government. The loss of Limbang had significant political and economic consequences for Brunei, as it relied on Limbang for food, forest produce, timber, fisheries, and other resources. The annexation also triggered further oppression, rebellion, and migration of Bruneians to Limbang.

The dispute over Limbang continued into the 20th century, with subsequent Sultans of Brunei making claims in 1951, 1963, and 1973. It was only in 2009 that a resolution was reached when Brunei and Malaysia signed the Exchange of Letters, agreeing to end all territorial disputes, including the Limbang claim, and establishing joint commercial arrangements for oil and gas exploitation in disputed maritime areas.

Exploring Brunei: A Fun Vacation Spot?

You may want to see also

The Brooke dynasty

Brooke ruled Sarawak with a handful of English assistants, making expeditions into the interior, suppressing headhunting, and establishing a secure government. He was knighted in 1848 and returned to England in 1863, leaving the government of Sarawak to his nephew, who succeeded him as the second raja upon his death in 1868.

The second raja, Sir Charles Anthony Johnson Brooke, adopted the surname Brooke and ruled Sarawak as a benevolent autocrat. He spent much of his life among the Iban people, knew their language, and respected their beliefs and customs. He made use of down-river Malay chiefs as administrators and encouraged selective immigration of Chinese agriculturalists, while the dominant indigenous group, the Ibans, were employed in military service. He was knighted in 1888 and was succeeded by his eldest son, Charles, upon his death in 1917.

The third and last "white raja", Sir Charles Vyner de Windt Brooke, joined the Sarawak administration in 1897. During his rule, Sarawak was drawn further into the world economy due to a boom in rubber and oil. The state embarked on gradual modernisation, developing public services and introducing a penal code. In September 1941, on the centenary of Brooke rule, the third raja proclaimed a constitution designed to establish self-government for Sarawak, but shortly afterward, the state fell to the Japanese. After World War II, Vyner Brooke decided to cede Sarawak to Great Britain, and Brooke rule formally ended on July 1, 1946.

Finding Employment in Brunei: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

The Sultanate ceded Sarawak to James Brooke

Brooke was highly successful in suppressing piracy in the region. However, his anti-piracy measures drew criticism, and he was officially investigated in Singapore. Despite this, he was honoured and feted in London for his activities in Southeast Asia.

In 1842, the Sultan ceded complete sovereignty of Sarawak to Brooke, who was granted the title of Rajah of Sarawak. Brooke ruled as the first White Rajah of Sarawak from 1841 until his death in 1868.

During his reign, Brooke worked to cement his rule over Sarawak. He reformed the administration, codified laws, and continued to fight piracy. He also pacified the native peoples, including the Dayaks, and suppressed headhunting.

Brooke's actions in Sarawak were directed at expanding the British Empire and securing his own personal wealth. He reorganised the government according to the British model and recruited European, chiefly British, officers to run district outstations. At the same time, he retained many of the customs and symbols of Malay monarchy, ruling with absolute power.

Brooke's nephew, Charles Brooke, succeeded him as the second White Rajah of Sarawak. The Brooke administrations continued to lease or annex more land from Brunei, contributing to the fragmentation of the Sultanate.

Vacationing in Brunei: A Safe Haven?

You may want to see also

The Treaty of Protection

The treaty was signed by Sultan Hashim Jalilul Alam Aqamaddin and the British government, with Sir Hugh Low representing Britain in the negotiations. The agreement was reached in response to geopolitical concerns about the growing influence of the German Empire and the United States in the region.

By signing the treaty, Brunei essentially handed over its foreign affairs to Britain, preventing the Sultan from holding direct talks with the neighbouring states of North Borneo and Sarawak. This marked a critical shift in Brunei's sovereignty, and the treaty's shortcomings were soon exposed. Just two years later, in 1890, Charles Brooke, the nephew and successor of James Brooke, annexed Limbang, significantly weakening Brunei and leading to further territorial losses.

Despite these challenges, Sultan Hashim remained committed to preserving Brunei's independence, even as financial strains worsened. However, his leadership was criticised by British officials, and sentiment shifted towards the government of Sarawak, which was perceived as offering more equitable taxes and better administration. The establishment of the British Residency system in Brunei further diminished the Sultan's authority, as actual power shifted to the British Resident.

In summary, the Treaty of Protection of 1888 significantly altered the course of Brunei's history, leading to a loss of sovereignty and territorial declines. It marked the beginning of a period where British interests took precedence, and the Sultan's role became increasingly symbolic, with limited influence over the country's affairs.

The Faces of Brunei: Exploring Asian Diversity

You may want to see also

Brunei's refusal to join the Malaysian Federation

Historical Grievances:

Brunei had a complex history with its neighbouring territories, which contributed to its reluctance to join the Malaysian Federation. The country had lost significant territory over the decades, including the cession of Kuching, Sarawak, to the British adventurer James Brooke in 1842. This marked the beginning of a series of territorial losses to the expanding Kingdom of Sarawak, which eventually left Brunei with two non-contiguous coastal parts, separated by Limbang. The loss of Limbang, an economically important town, to Sarawak's Rajah Charles Brooke in 1885 was a particularly bitter pill to swallow and played a role in Brunei's wariness of further integration with its neighbours.

Political and Economic Considerations:

Brunei had legitimate concerns about the potential loss of political autonomy and control over its natural resources, particularly oil, if it joined the Malaysian Federation. The country wanted to retain its sovereignty and decision-making power regarding key aspects of governance, such as the number of seats in the legislature and parliament, control of oil and gas exploration and production, and authority in education and welfare. Additionally, there was widespread anti-Federation sentiment within Brunei, with many favouring the establishment of a North Borneo Federation that included the three crown colonies of northern Borneo, which was seen as a way to counter potential domination by Malaya or Singapore.

Preserving Sovereignty:

The Sultan of Brunei, Sir Omar Ali Saifuddin III, wanted to ensure that the country retained its independence and self-governance. Brunei was already a British protectorate, and the Sultan was cautious about entering into another arrangement that might compromise its sovereignty. The country's oil wealth gave it leverage in negotiations, and it wanted to maintain control over its natural resources and the revenue they generated. Brunei's refusal to join the Malaysian Federation ultimately led to its independence from the United Kingdom in 1984.

Golden Jubilee of Brunei: Celebrating 50 Years of Royalty

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Brunei is split into two by the Malaysian state of Sarawak, specifically the Sarawak district of Limbang.

The current territory of Brunei is the result of a series of historical events. In the 19th century, the Bruneian Empire began to decline and lost territory to the Brooke dynasty, known as the White Rajahs. In 1883, the Kingdom of Sarawak, ruled by Charles Brooke, nephew of James Brooke, extended up to the Baram River, which is approximately the western boundary of modern Brunei. Two years later, in 1885, Charles Brooke seized the town of Limbang, which split the remaining territory of Brunei into two.

The two parts of Brunei are surrounded by the Malaysian state of Sarawak and have coastlines on the South China Sea and Brunei Bay. The western part of Brunei, where most of the population resides, consists of the valleys of the Belait, Tutong, and Brunei rivers and is mainly hilly. The eastern part, the Temburong district, contains the Pandaruan and Temburong river basins and the country's highest point, Pagon Peak.