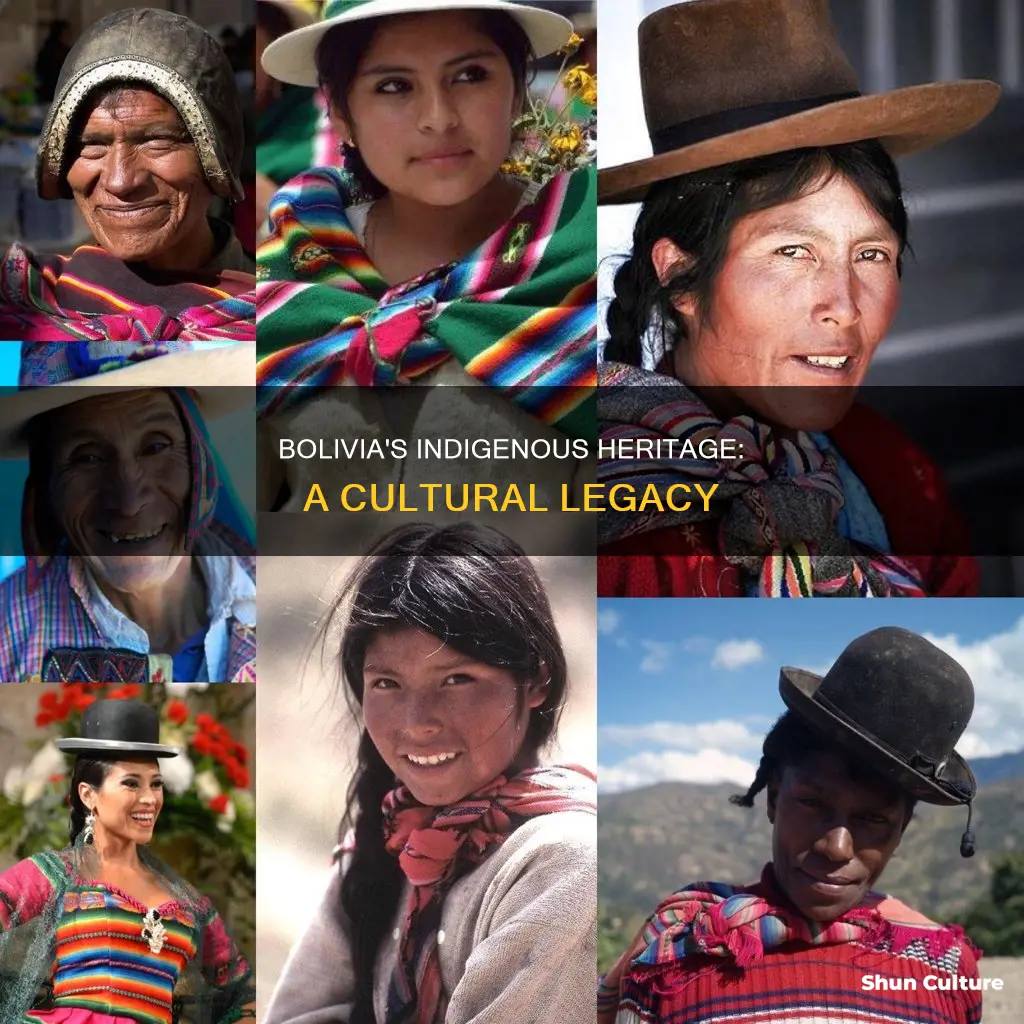

Bolivia has a large indigenous population, with estimates ranging from 20 to 60% of the country's total population. The 2012 National Census recorded that 41% of Bolivians aged 15 or over are of indigenous origin, though this number is likely to have increased to 48% according to 2017 projections. There are 36 recognised indigenous groups in Bolivia, with the largest communities being the Quechua and Aymara peoples, who make up around half of the country's indigenous population. The country's indigenous peoples have a long history of marginalisation and lack of representation, but there have been significant improvements in recent years, including constitutional recognition, popular participation, bilingual education, and greater political representation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Percentage of Indigenous People in Bolivia | 41% of the population over 15 years old in 2012, projected to increase to 48% in 2017 |

| Number of Recognised Indigenous Peoples | 36-38 |

| Main Indigenous Groups | Highland: Aymara and Quechua; Lowland: Chiquitano, Guaraní, and Moxeño |

| Languages | Spanish, Quechua, Aymara |

| Religion | Christianity (Roman Catholic, Evangelical, Pentecostal, and Protestant) and Indigenous Religions |

| Land Rights | 23 million hectares of collective property under the status of Community Lands of Origin (TCOs) |

| Political Mobilisation | The 1952 Bolivian National Revolution, Kataraista movement, and social movements in the 1990s and 2000s |

| Current President | Evo Morales, the first Indigenous President |

What You'll Learn

- Bolivia's adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- The country's 36 recognised ethnic groups

- The impact of marginalisation and lack of representation

- The rise of political and social mobilisation in Indigenous communities

- The election of Evo Morales, Bolivia's first Indigenous president

Bolivia's adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Bolivia has long been notable for its indigenous majority, with 62% of Bolivians aged 15 or over self-identifying as indigenous in the country's 2001 census. However, the country's most recent census in 2012 saw a significant reduction in this number, with just 41% of Bolivians aged 15 or over identifying as indigenous.

In 2007, Bolivia became the first country to introduce the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples into local law. The UN Declaration is one of the broad international instruments compared to other instruments concerning minorities (currently, 148 countries support the UN Declaration). Its value lies in its defense and protection of indigenous peoples as permanent societies, and its respect for ethnic and cultural diversity. The UN Declaration also ratifies the rights to identity, culture, language, systems of writing and literature, oral traditions, health, work, education, and other rights.

With the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and a new Constitution, Bolivia took the name of a plurinational state. The new Constitution, formally approved in 2009, provides for the development of a comprehensive legal framework. One of the most prominent laws is the 2010 Law against Racism and All Forms of Discrimination, also known as Law 045, which criminalizes a range of racist or discriminatory actions, including violent incitement and the dissemination of racist or discriminatory material through media and other means.

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Bolivia's new Constitution are important milestones in the recognition and protection of the rights of indigenous peoples in the country. The adoption of these laws has helped to address historical injustices and promote the cultural diversity and well-being of indigenous communities in Bolivia. However, despite these legal advancements, challenges remain, and further efforts are needed to fully protect and promote the rights of indigenous peoples in the country.

Streaming Guide: Argentina vs Bolivia

You may want to see also

The country's 36 recognised ethnic groups

Bolivia's 36 recognised ethnic groups, or 38 according to some sources, are predominantly Amerindian. The largest groups are the Aymara and Quechua, who make up around half of the country's indigenous population. The Aymara are mainly found in La Paz, while the Quechua are the majority in Cochabamba. Both groups share many cultural attributes, such as their belief in Pachamama, an Andean deity often translated as 'Earth Mother'.

In the Andes, the majority of indigenous people are Quechua-speaking (49.5%) and self-identify as 16 nations. In the lowlands, the Chiquitano (3.6%), Guaraní (2.5%), and Moxeño (1.4%) peoples are in the majority, making up 20 recognised indigenous peoples. Other indigenous groups include the Uros, who live beside lakes and rivers and use traditional reed boats for fishing, and the Chipaya, who number around 2,000 and live in the salty marshes in southwest Bolivia, close to the Chilean frontier.

In addition to the 36 recognised ethnic groups, there are also minority groups in Bolivia, including Afro-Bolivians, and small communities of Japanese and Europeans, including Germans (Mennonites).

Best Streaming Platforms: Brazil vs Bolivia Match

You may want to see also

The impact of marginalisation and lack of representation

Indigenous peoples in Bolivia have historically faced marginalisation and a lack of representation. Despite constituting a significant proportion of the country's population, they have been marginalised and exploited for labour in mines and plantations. This marginalisation has resulted in a lack of political power and representation for indigenous communities, who have been fighting for their rights and recognition.

The late twentieth century saw a surge of political and social mobilisation among Indigenous communities in Bolivia, with movements such as the Kataraista movement advocating for Indigenous concerns and pursuing an Indigenous political identity. The 1952 Bolivian National Revolution, which liberated Bolivians and granted Indigenous peoples citizenship, was a significant step towards inclusion. However, it fell short in providing adequate political representation for Indigenous communities.

Indigenous peoples in Bolivia, or Native Bolivians, have faced systemic marginalisation and exclusion from mainstream society. They were often denied equal opportunities and access to resources, resulting in a lack of representation in various sectors, including politics, media, and education. This marginalisation has had a significant impact on their social, economic, and political rights, as well as their overall well-being.

The lack of representation has led to Indigenous peoples being overlooked and their issues remaining unaddressed. In the political sphere, their voices were often absent or drowned out by the dominant groups, resulting in policies and decisions that did not consider their unique needs and perspectives. This lack of representation has also contributed to the perpetuation of negative stereotypes and discrimination against Indigenous peoples, further exacerbating their marginalisation.

Additionally, the lack of representation in decision-making processes has led to policies and initiatives that fail to address the specific needs of Indigenous peoples. Their unique cultural and linguistic traditions may not be adequately supported or preserved, leading to a potential loss of cultural identity and a sense of disconnect from their heritage. This can have a detrimental effect on the mental health and well-being of individuals within these communities.

Furthermore, the marginalisation and lack of representation have also impacted Indigenous peoples' ability to protect their land and natural resources. Without a strong political voice, they have often been unable to prevent destructive environmental practices, such as seismic work for oil and gas exploration, or hydroelectric projects that directly affect their territories and way of life. This has resulted in a constant struggle to safeguard their ancestral lands and maintain their cultural practices and traditions.

In conclusion, the marginalisation and lack of representation faced by Indigenous peoples in Bolivia have had far-reaching consequences. It has led to social, economic, and political disadvantages, as well as a struggle to preserve their cultural identity and way of life. However, despite these challenges, Indigenous communities have demonstrated resilience and a strong will for change, as evidenced by their increasing political mobilisation and the election of Evo Morales, Bolivia's first Indigenous president.

Shipping to Bolivia: Safe or Not?

You may want to see also

The rise of political and social mobilisation in Indigenous communities

Bolivia has a long history of Indigenous peoples, with several groups inhabiting territories in the country for thousands of years before the arrival of Spanish colonial forces in the early 16th century. Despite this, Indigenous communities in Bolivia have historically faced marginalization and a lack of representation. However, the late 20th century saw a surge of political and social mobilization among these communities, which has continued into the 21st century.

The Katarista Movement

The Katarista movement, consisting of the Aymara communities of La Paz and the Altiplano, emerged in the 1960s and 1970s as one of the first social movements to include Indigenous concerns in its agenda. The movement attempted to mobilize the Indigenous community and pursue an Indigenous political identity through mainstream politics and life. While the Katarista movement failed to create a national political party, it influenced many peasant unions and laid the groundwork for future Indigenous political mobilization.

The 1990s and Beyond

The 1990s saw a significant increase in political mobilization among Indigenous communities in Bolivia, with President Sánchez de Lozada passing reforms to acknowledge Indigenous rights in Bolivian culture and society. However, many of these reforms fell short, and the government continued to pass policies that negatively impacted Indigenous communities, particularly regarding environmental issues and land rights.

One of the most prominent issues during this period was the government-backed privatization and eradication of natural resources and landscapes, which sparked widespread protests from Indigenous communities. Coca leaf production, an important sector of the Bolivian economy and culture, especially for Indigenous peoples, was a particular point of contention. Protests against the eradication of coca leaf production, heavily supported by the United States' war on drugs, led to violent clashes between protestors and police officials.

The Election of Evo Morales

The coca leaf movement found a vocal opponent to the eradication of coca production in Evo Morales, a leader of the coca leaf movement who would go on to become Bolivia's first Indigenous president. Under Morales' leadership, the coca leaf producers formed coalitions with other social groups and eventually created a political party, the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS).

Morales' election in 2005 marked a significant victory for Bolivia's Indigenous communities. As president, Morales attempted to establish a plurinational and postcolonial state to expand the collective rights of Indigenous communities. The 2009 constitution recognized the presence of the different communities residing in Bolivia and granted Indigenous peoples the right to self-governance and autonomy over their ancestral territories.

Ongoing Challenges and Mobilization

While Bolivia has made significant progress in recognizing and protecting the rights of Indigenous communities, challenges remain. Land rights continue to be a serious issue, with Indigenous communities facing threats from extractive industries and colonization. Additionally, despite constitutional reforms acknowledging the multi-ethnic and multicultural nature of the country, many Indigenous communities still face marginalization and social exclusion.

Indigenous communities in Bolivia have continued to mobilize and protest against policies that negatively impact their rights and well-being. Examples include the 2011 Indigenous march against a government plan to build a highway through a national park in Indigenous territory and the ongoing struggle against seismic work in search of new oil and gas reserves and hydroelectric projects.

Exploring Bolivia's Unique Regional Location

You may want to see also

The election of Evo Morales, Bolivia's first Indigenous president

Bolivia has long been notable for its indigenous majority, with 62% of Bolivians aged 15 or over self-identifying as indigenous in the country's 2001 census. However, the 2012 census saw a significant reduction in this number, with just 41% of Bolivians aged 15 or over identifying as indigenous. This shift is attributed in part to factors such as urbanisation, as indigenous identity in Bolivia is strongly tied to conceptions of the rural 'campesino' (peasant).

After winning the election, Morales promptly enacted one of history's most dramatic countermovements by nationalising Bolivia's industries and rewriting the constitution to ensure that the country's natural resources would be used for the benefit of the people. Morales's victory was not an isolated episode but was part of a region-wide political shift to the left in response to the social devastation of the neoliberal period.

Morales's success also marked a symbolic victory over colonialism and signified a new beginning or even a second independence for Latin America. As the continent's first indigenous president, Morales is the embodiment of South American self-governance and a living symbol of the end of colonial oppression. An extremely self-aware politician, Morales's campaign embraced the historical symbolism of his election, infusing his rhetoric with iconic language:

> I want to say to all my indigenous brothers from America, here in Bolivia today, that [the] campaign of 500 years of resistance hasn't been in vain. Enough is enough. We are taking over now for the next 500 years.

Since his election, Morales has enjoyed a period of unbroken rule. While there have been many positive outcomes during this period, including many positive steps for the minority and indigenous population, problems of poverty and discrimination have persisted.

Exploring Bolivia's Bike Trails: An Adventure Unveiled

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bolivia has a long history of indigenous populations, with several groups inhabiting the land for thousands of years before the arrival of Spanish forces in the early 16th century. Today, Bolivia is home to 36 recognized indigenous groups, with the largest communities being the Highland Aymara and Quechua in the Andes, and the Chiquitano, Guaraní, and Moxeño in the lowlands. According to the 2012 census, 41% of Bolivians aged 15 or older identified as indigenous, although this number is estimated to have increased to 48% by 2017.

One of the major challenges for indigenous peoples in Bolivia is the impact of seismic work and the search for new oil and gas reserves, as well as hydroelectric projects. These projects often directly affect the territories inhabited by indigenous peoples and peasants. Additionally, issues of land rights and environmental destruction continue to be a concern, with indigenous communities struggling to protect their ancestral territories from extractive industries.

There have been several advancements in recent years for indigenous peoples in Bolivia. The election of Evo Morales, Bolivia's first indigenous president, in 2005, was a landmark moment. Morales worked to address the marginalization of the country's indigenous population and the 2009 constitution recognized the presence and rights of the different indigenous communities in the country. Additionally, the Framework Law on Autonomies of 2010 allowed several indigenous peoples to form their own self-governments. Constitutional reforms in 2004 also acknowledged the 'multi-ethnic and multicultural' nature of the republic, recognizing the right of indigenous peoples to full and effective political participation.