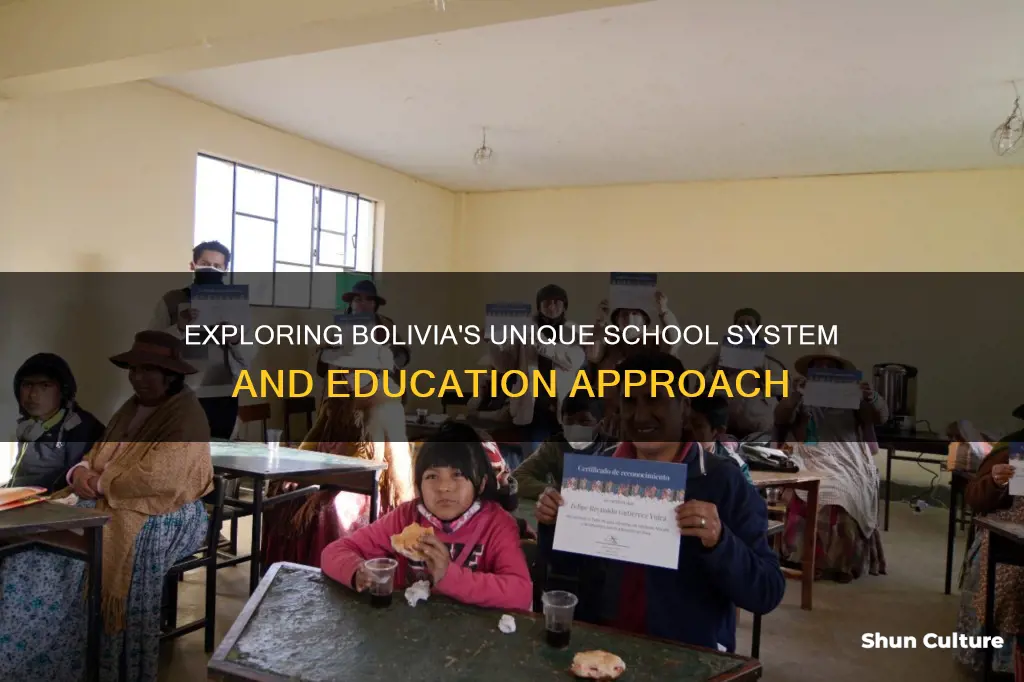

Bolivia's education system has a long history of inequality between urban and rural areas. While the country has made significant strides towards improving literacy rates, there are still issues with a lack of access to education in rural areas, as well as a disparity in the quality of education provided by public and private institutions. The Bolivian government has shown commitment to improving the situation, with education accounting for 23% of its annual budget, a higher percentage than most other South American countries. However, the system continues to face challenges, including underfunding, high dropout rates, and a lack of resources and organisation in public schools.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Primary Education | 5-year mandatory program for 6- to 10-year-olds or 7- to 14-year-olds |

| Intermediate Education | 3-year program for 11- to 13-year-olds |

| Secondary Education | 4-year program for 14- to 17-year-olds |

| Compulsory Education | Until the age of 14 |

| Language of Instruction | Spanish |

| School Year | February to November |

| Summer Vacation | December and January |

| School Hours | 4 hours per day, either in the morning or afternoon |

| Meals | Not provided by most schools |

| Uniforms | Required by most schools |

| Transportation | Not provided by most schools |

| Extracurricular Activities | Not included in most school curricula |

| Public vs. Private Education | 87% of children attend public schools, but only 35% continue to high school |

| Adult Literacy | Increased from 17% in 1900 to 80% by the end of the 20th century |

What You'll Learn

Primary, intermediate and secondary education

Primary, intermediate, and secondary education in Bolivia is divided into three cycles, or four if you include the optional preschool or preprimary years. The primary cycle consists of five years of elementary education for children aged 6 to 10. This is followed by three years of intermediate education in middle schools for 11- to 13-year-olds. The secondary cycle comprises four years of education for 14- to 17-year-olds.

The four years of secondary school are further divided into two cycles lasting two years each. The first cycle is a common core curriculum, while the second cycle allows students to specialize in either the humanities or a range of technical fields. There is a movement to integrate both intermediate and secondary levels into a single eight-year cycle.

Primary education in Bolivia was introduced in the 1970s and is currently a five-year mandatory program, followed by three years of intermediate school. However, the attendance rate beyond primary school drops significantly, with only about 35% of students continuing on to high school. This disparity is more pronounced in rural areas, where only around 40% of children receive primary education beyond the third grade.

Spanish is the primary language of instruction at all levels of primary and secondary education in Bolivia. The school year typically runs from February to November, with December and January being the summer vacation months.

Hispanics in Bolivia: Exploring Cultural Identity and Heritage

You may want to see also

School attendance and dropout rates

Bolivia has a long history of educational inequality between its rural and urban areas. While the country has made significant strides in literacy and access to education since the 1950s, it continues to face challenges with school attendance and dropout rates, especially in rural areas and among girls.

In the late 1980s, only about one-third of first graders completed the fifth grade, with 20% starting secondary school, 5% beginning post-secondary studies, and just 1% receiving a university degree. These statistics highlight the low continuation rates in the Bolivian education system. Dropout rates were significantly higher among girls and rural children, with only around 40% of rural students continuing their education beyond the third grade. This disparity is partly due to the harsh economic realities faced by poorer families, who rely on their daughters' contributions to household chores and childcare.

The lack of bilingual education has also been cited as a contributing factor to high dropout rates among rural students. In the late 1980s, Spanish was the sole language of instruction, despite less than 50% of the population speaking it as their first language. This language barrier likely contributed to the low completion rates among rural students, with 71% not reaching five years of schooling.

The quality of education also varies between urban and rural areas. The Bolivian public education system, particularly in rural regions, faces criticism for its lack of organisation and quality. Schools often lack adequate furnishings and classroom materials, and teacher strikes over wages and other issues can lead to prolonged school closures. These factors may contribute to low attendance and high dropout rates, especially among those who cannot afford private education.

The Bolivian government has made efforts to address these issues, including increasing educational expenditures to 23% of its annual budget, which is a higher percentage than most other South American countries. However, implementation challenges and resistance from teachers' unions have slowed down progress.

Growing Bolivian Torch: A Time-Consuming Process Explained

You may want to see also

Rural vs urban education

The state of education in Bolivia is heavily influenced by the rural-urban divide, with rural illiteracy levels remaining high while urban areas become increasingly literate. This disparity is further exacerbated by the lack of public educational infrastructure in rural areas, with most educational expenditures skewed towards urban areas. As a result, rural students face higher dropout rates and lower educational attainment compared to their urban counterparts.

In rural Bolivia, the average duration of studies is significantly lower than in urban areas, with children in rural areas attending school for about 4.2 years, compared to 9.4 years in cities. This gap in educational opportunities is partly due to the lack of public investment in rural areas, with 60% of Bolivia's 59,000 teachers employed in urban schools. The quality of education in rural areas is also impacted by the language and cultural barriers between teachers and students, with teachers often not speaking the local language, making it difficult for children to learn Spanish, the primary language of instruction.

Additionally, rural families often rely on their children's labour in agricultural work and face economic challenges that hinder their ability to prioritise education. This results in higher absenteeism and dropout rates among rural students, particularly among girls, who are often disadvantaged when it comes to accessing education. The lack of bilingual education or intercultural bilingual education has also been cited as a contributing factor to the high dropout rates among rural students.

On the other hand, urban areas in Bolivia have seen improvements in literacy rates and increased enrolment in primary and secondary education over the years. However, the quality of urban education is still a concern, with public schools facing issues such as inadequate maintenance, lack of furnishings, and insufficient classroom materials. The surge in privately owned institutes, schools, and universities in recent years has provided an alternative for those who can afford it, further widening the educational gap between urban and rural students.

Despite efforts to implement comprehensive education reforms since 1994, resistance from teachers' unions and political instability have slowed down the progress. Bolivia's dedication to education is evident, with 23% of its annual budget allocated to educational expenditures, but the impact of these investments is yet to be fully realised, especially in rural areas where educational needs are the greatest.

Exploring Bolivia's Population Density: Understanding the Landscape

You may want to see also

Language of instruction

The language of instruction in Bolivia is primarily Spanish, with the country also boasting 36 recognised indigenous languages. However, the absence of bilingual education has been blamed for high dropout rates among rural schoolchildren, many of whom speak Quechua, Aymara, or other indigenous dialects and struggle with Spanish-language instruction.

In the 1990s, educational reforms were initiated to address this issue, formalising and expanding intercultural bilingual education. However, resistance from teachers' unions has slowed the implementation of these reforms.

The issue of language instruction is particularly pressing in rural areas, where only around 40% of children attend school beyond the third grade. This is in stark contrast to urban areas, where the level of education is much higher, with children attending school for an average of 9.4 years.

The Bolivian government has made primary education compulsory up to the age of fourteen, but enforcing school attendance can be difficult in some areas. As a result, while around 87% of children attend primary school, only about 35% make it to high school.

The lack of bilingual education is not a new issue in Bolivia. Historically, education was limited to the sons of elite families, with little effort made to teach indigenous children beyond what was necessary for conversion to Christianity. Even after independence, when several decrees were passed to make elementary-level learning and attendance compulsory, little progress was made in expanding educational opportunities for indigenous communities.

It was not until the early 1900s, when a teaching mission from Belgium arrived, that a foundation for rural primary education was established. Despite this, as of the late 1980s, Spanish remained the primary language of instruction at all levels of the education system.

Bolivia on a Budget: Flight Costs and Tips

You may want to see also

School funding and costs

Bolivia devotes 23% of its annual budget to educational expenditures, a higher percentage than in most other South American countries. However, this is from a smaller national budget. A comprehensive education reform was initiated in 1994, which decentralized educational funding to meet diverse local needs. Despite improvements, the Bolivian public education system is criticized for its lack of organization and quality. State schools are underfunded and poorly maintained, with inadequate furnishings and classroom materials.

The first six years of primary school are free and compulsory, but in practice, around 20% of children do not attend. The four years of secondary education are non-compulsory, with less than a quarter of young adults attending. Those who do, mainly attend private schools, which are more accessible to those from wealthier backgrounds.

The Bolivian education system is split into three cycles, with an optional pre-primary stage. The primary cycle is for children aged 6-10, the intermediate cycle for 11-13-year-olds, and the secondary cycle for 14-17-year-olds. The secondary cycle is divided into two, with the first two years being a common core, and the second two allowing for specialization in either the humanities or technical fields.

The University of Bolivia, a consortium of eight public universities and one private university, was the only post-secondary school that awarded degrees. However, there are also numerous private schools and universities, which have become increasingly popular due to the issues within the state system.

Exploring Bolivia's Drug-Related Deaths: A Sobering Reality

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The school system in Bolivia is divided into three cycles, with an optional fourth cycle for preschool or preprimary years. The first cycle is primary education, which is five years of elementary education for 6- to 10-year-olds. The second cycle is three years of intermediate education in middle schools for 11- to 13-year-olds. The third cycle is four years of secondary education for 14- to 17-year-olds. The four years of secondary education are further divided into two cycles lasting two years each. The first cycle is a common core, while the second allows students to specialize in the humanities or a technical field.

Primary and secondary schools in Bolivia are regulated by the Ministry of Education, which outlines guidelines for curriculum, accreditation, and teacher salaries. The schools are a mix of public and private institutions, with the public schools often lacking in terms of organization and quality. The public schools are usually not well-maintained and often lack adequate furnishings or classroom materials. Teachers' strikes are also common, which can lead to school closures for extended periods. However, many public schools are supported by non-profit institutions, and these schools are typically in excellent condition with higher learning levels.

Education in Bolivia has a long history of division between rural and urban areas. During colonial times, only the sons of the elite were educated, and little effort was made to teach the natives or women of any social class. After Bolivia gained independence, several decrees were passed to make elementary education and attendance compulsory, but these were not effectively implemented. In the early 1900s, a teaching mission from Belgium laid the foundation for rural primary education over a thirty-year period. In 1947, the Bolivian government passed a literacy law, and in 1956, legislation was enacted to establish the public school system that still exists today.

The Bolivian school system faces challenges such as high dropout rates, especially among rural and female students. There is also a disparity in education levels between urban and rural areas, with many rural children working to contribute to their family income. Additionally, the government has struggled to improve the school system, leading to a surge in privately owned institutes, schools, and universities. However, efforts are being made to improve the system, with Bolivia devoting 23% of its annual budget to educational expenditures, higher than most other South American countries. A comprehensive education reform initiated in 1994 aims to decentralize funding, improve teacher training and curricula, and expand intercultural bilingual education.