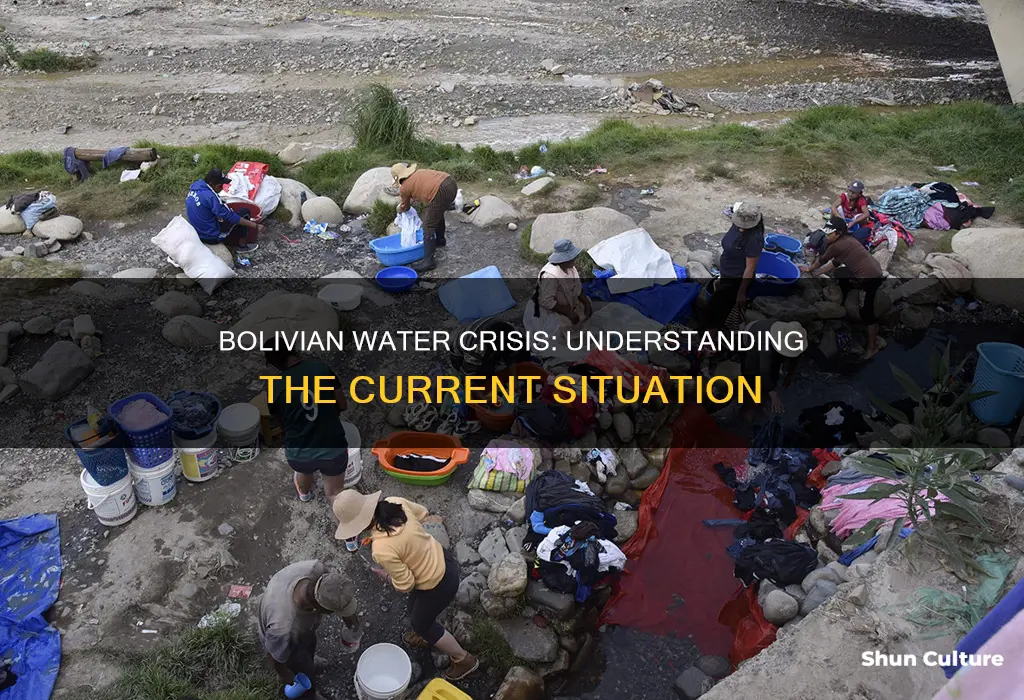

Bolivia is currently facing a severe water crisis, with the country suffering from what has been described as its worst drought in 25 years. The situation has led to a national state of emergency being declared by President Evo Morales, who has also imposed stricter water rationing and fired a top water official. This crisis comes two decades after the infamous Cochabamba Water Wars, in which thousands of Bolivians protested against the privatisation of water, resulting in the death of 17-year-old Hugo Victor Daza. Today, Bolivia continues to struggle with water shortages, with issues such as population growth, deforestation, and glacier melt all contributing to the country's water woes.

What You'll Learn

Water privatisation

Bolivia has faced a severe water crisis in recent years, and water privatisation has been a significant issue. In the late 1990s, the Bolivian government privatised water supply and sanitation, granting concessions to private companies. This led to protests and the Cochabamba Water War in 2000, where thousands of people demonstrated against the privatisation and the resulting increase in water prices.

The Lead-Up to the Cochabamba Water War

The privatisation of water supply and sanitation in Bolivia occurred during the second mandate of President Hugo Banzer, between 1997 and 2001. Two major concessions were granted:

- In 1997, Aguas del Illimani S.A. (AISA), a subsidiary of the French company Suez, was granted a concession in La Paz/El Alto.

- In 1999, Aguas del Tunari, a consortium that included the US company Bechtel, was awarded a concession in Cochabamba.

The World Bank and the International Development Bank pressured the Bolivian government to privatise water as a requirement to retain ongoing state loans. The privatisation process was met with criticism as it did little to address water access issues, and the increase in water prices contributed to a rise in poverty levels.

The Cochabamba Water War

The Cochabamba Water War, also known as the Bolivian Water War, took place in Cochabamba, Bolivia's fourth-largest city, from December 1999 to April 2000. The conflict was sparked by the privatisation of the municipal water supply company, SEMAPA, and the subsequent increase in water rates.

Protests were largely organised by the Coordinadora (Coalition in Defense of Water and Life), a community coalition. The demonstrations turned violent, with clashes between protesters and the police. On April 8, 2000, the government of Hugo Banzer declared a state of siege, and martial law was imposed. During the protests, a 17-year-old student, Víctor Hugo Daza, was shot and killed by the Bolivian Army.

Outcome of the Protests

The protests ultimately led to the reversal of privatisation. On April 10, 2000, the national government reached an agreement with the Coordinadora to revoke the privatisation law. The water supply in Cochabamba returned to public hands.

Impact and Legacy

The Cochabamba Water War was a significant event in the fight for the right to water in Latin America. It inspired similar protests against water privatisation in other parts of Bolivia and raised awareness about the issue globally.

However, Bolivia continues to face water-related challenges. Rural areas lack water security, and many people do not have access to adequate sanitation. Additionally, Bolivia is one of the countries most threatened by climate change, with rising temperatures and the impacts of El Niño leading to severe droughts and flooding.

Bolivia's High-Altitude Haven: Exploring the Rarefied Air

You may want to see also

Climate change

Bolivia is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change, despite being one of the lowest emitters of greenhouse gases. The country is experiencing a severe water crisis, with around three million people in rural areas lacking water security and five million without access to adequate sanitation.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) warned in a 2013 report that the Andean highlands would face significant challenges due to climate change. The report predicted that the average temperature in Bolivia would rise by up to 2°C by 2030 and between 5-6°C by 2100. This increase in temperature is largely due to the existence of diverse ecosystems and growing deforestation. The report also highlighted the impact of severe flooding and prolonged droughts in certain regions, caused by El Niño.

Bolivia's water crisis is a direct consequence of climate change. In 2016, the country experienced its worst drought in decades, with the cities of Oruro, Potosí, Cochabamba, Sucre, and La Paz being the most affected. The drought led to a state of national emergency, with some areas in the highlands losing up to 90% of their crops. The drying up of Lake Poopó, located in the Oruro highlands, is a visible example of the water crisis. The lake has historically been unstable, and its volume has decreased due to reduced rainfall.

While climate change is a significant factor, other issues such as population growth, water infrastructure, and mismanagement have also exacerbated Bolivia's water crisis. The urban areas of La Paz and El Alto are growing by 40,000 to 50,000 people each year, putting a strain on the existing water supply systems. Additionally, there are significant water losses, ranging from 40 to 50%, due to outdated water pipes, open canals, infiltrations, and illegal access.

Action Against Hunger: Transforming Lives in Bolivia

You may want to see also

Population growth

Bolivia's population has been growing rapidly, with a current population of around 12.5 million people. This is a significant increase from 8.2 million in 2001 and over three times the population from 50 years ago. The population growth rate has been steadily slowing since 1980, and that trend is expected to continue. The country's population is projected to peak at 17.67 million in 2083, after which it will begin to slowly decline.

The birth rate in Bolivia is still above the death rate, but it is declining, along with the fertility rate. The fertility rate is currently 2.75 births per woman, which is above the population replacement rate of 2.1 births. The population growth rate has decreased from 1.71% in 2010 to 1.39% currently. This is due to the falling birth and fertility rates, as well as thousands of people emigrating from the country each year.

The population density in Bolivia is low, with only around 11 people per square kilometre. About 70% of the population lives in urban areas, with 70% of people concentrated in the cities of La Paz, Santa Cruz, and Cochabamba. Santa Cruz de la Sierra is the largest city, with 3.32 million people, followed by La Paz with 2.4 million, and El Alto with 2.3 million.

The median age in Bolivia is 24.9 years, and the country has a diverse population with more than three dozen native groups. The largest groups are the Quechuas and Aymaras, who make up 60% of the population, including the Andean people. The full Amerindian population is 55%, with 30% mestizo and 15% white. Many mestizos in Bolivia also identify with indigenous cultures.

Guinea Pigs: Bolivia's Traditional Delicacy

You may want to see also

Water infrastructure

Bolivia's water infrastructure has been a mix of \"big system\" and \"small system\" approaches, with varying levels of public and private involvement. \"Big system\" infrastructure refers to a centralised model where a single operator manages the piped system, while \"small system\" infrastructure involves informal control of water resources by individuals.

In the late 1990s, the cities of La Paz and El Alto faced challenges with their water supply, with the poorest communities suffering the most from shortages and decreased access. This prompted the decision to privatise the water system, with contracts signed in 1997 with Aguas del Illimani, a subsidiary of the French company Suez. However, this privatisation effort faced obstacles due to the company's inability to provide water access to the poorest households. As a result, Aguas del Illimani was replaced by a public utility, Empresa Pública Social de Agua y Saneamiento (EPSAS), in 2007.

The transition back to public management in 2007 was driven by the recognition that privatisation had failed to adequately address water access issues. However, the public water utility also encountered challenges, such as a major setback in 2008 when a landslide destroyed pipes in the Pampahasi system, disrupting water supply to parts of La Paz for several weeks.

To address the ongoing water crisis, Bolivia's president Evo Morales has declared a national state of emergency, tightened water rationing, and proposed infrastructure projects. The current crisis is attributed to a combination of factors, including foreign mines near reservoirs, government planning, and the impact of climate change on glaciers and water sources.

To improve water infrastructure and address the crisis, a blend of "big system" and "small system" approaches has been proposed. \"Small systems\" are particularly relevant in rural areas and on western slopes that are not suitable for "big systems". These small-scale, community-managed systems can provide water without undermining the larger piped systems and are more easily maintained.

In addition to infrastructure improvements, efforts to promote water conservation and address the impacts of climate change are crucial. Bolivia's glaciers have shrunk significantly, reducing a vital source of drinking water, irrigation, and hydropower. Deforestation in the lowlands has also contributed to climate change, further exacerbating the water crisis.

Overall, the water infrastructure in Bolivia has been a complex interplay between public and private management, centralised and decentralised systems, and ongoing efforts to address water scarcity and the impacts of climate change.

The Plunder of Bolivia: Morales' Theft and Corruption

You may want to see also

Water conservation

Bolivia has a history of water shortages and water privatisation, with the Cochabamba Water War of 2000 being a significant moment in the fight for the right to water in Latin America. The country has taken steps towards improving water conservation and management, but it still faces challenges due to climate change, deforestation, and mismanagement. Here are some measures that Bolivia has undertaken or proposed to address water conservation:

- Reciprocal Water Agreements (ARA): This innovative approach, pioneered in Bolivia, encourages collaboration between rural and urban inhabitants of the same watershed to protect forests and their water sources. In return for protecting water-producing forests, farming families receive incentives to develop sustainable practices and gain access to drinking water. This model has been successful, with an increasing number of farmers committing to protect their forests.

- Water Committees: These committees are a form of social empowerment and a guarantee of resilience in the face of water scarcity. They gather knowledge on water resources management, climatology, and emergency response, and promote water culture within their communities.

- Institutional and Legal Framework: Evo Morales' administration is working on creating a new Water Law to replace the one from 1906 and increase participation, especially for rural and indigenous communities. The new law will aim to separate the water sector from privatisation policies and address issues of water access and pricing.

- Environment and Water Resources Ministry: Created in 2009, this ministry is responsible for planning, implementing, monitoring, evaluating, and funding policies and plans for water resources management. It consists of three vice ministries focusing on water supply, water resources, and the environment.

- Water Pricing and Subsidies: The current approach to water pricing and subsidies varies and can be confusing. The new Water Law is expected to address these issues and introduce a preferential electricity tariff for water service providers, strengthening community water rights.

- International Cooperation: Bolivia has received support from international organisations such as the Inter-American Development Bank, the World Bank, and the Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR) to improve water resources management and adapt to climate change.

While Bolivia has made strides towards water conservation, it continues to face challenges due to climate change, deforestation, and water mismanagement. These measures aim to address these issues and improve water security for the country's population.

Anchorage's Bolivian Money Access: A Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bolivia is currently facing one of its worst droughts in 25 years, with water shortages affecting the cities of La Paz and El Alto. The situation has been exacerbated by a combination of factors, including foreign mining, government planning, and climate change. As a result, President Evo Morales has declared a national state of emergency and imposed stricter water rationing to remediate the crisis.

The water crisis in Bolivia has multiple causes, including melting glaciers due to climate change, inadequate water infrastructure, and population growth. Bolivia's glaciers have shrunk by 43% between 1986 and 2014, reducing the availability of water for drinking, irrigation, and hydropower. Additionally, the urban areas of La Paz and El Alto are growing by 40,000 to 50,000 people each year, putting further strain on the water supply.

To address the water crisis, the Bolivian government has implemented stricter water rationing and proposed infrastructure projects. However, critics argue that the government has failed to secure alternative water supplies and improve water conservation efforts. In addition, "water committees" have been formed to empower local communities and promote water culture. International organizations, such as Water For People, are also working to improve access to water and sanitation services in Bolivia.