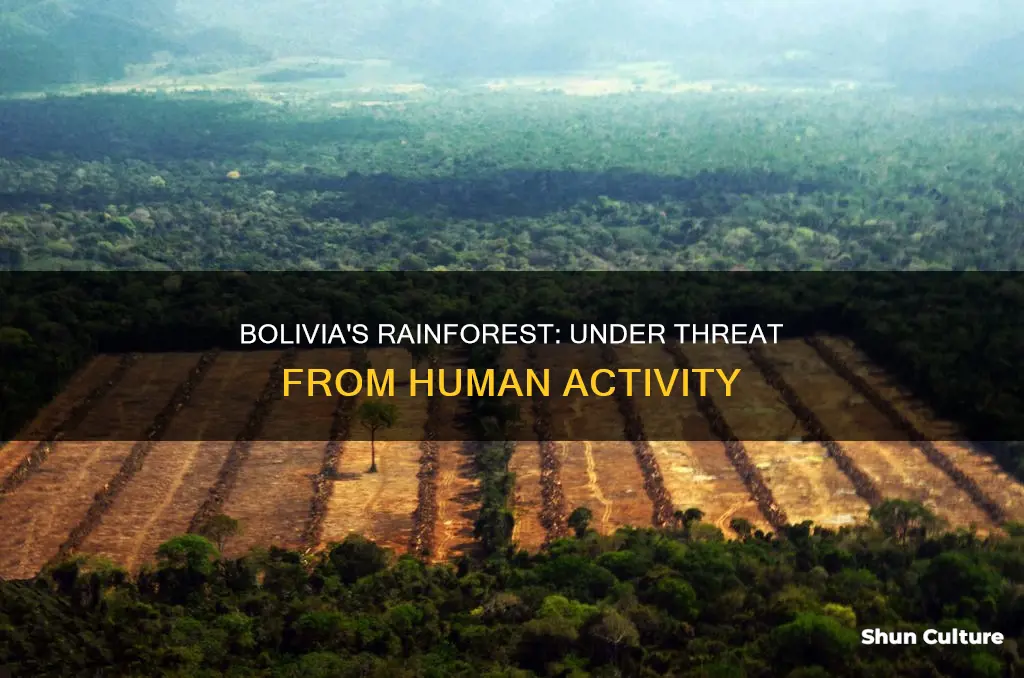

Bolivia's rainforest is being hurt by a combination of factors, primarily driven by human activity and governmental policies. Between 1976 and 2021, Bolivia lost approximately 8.6 million hectares of its forests, which is equivalent to 14% of its total forest cover. This massive deforestation is largely due to the expansion of agricultural surfaces for cattle ranching and soy production, facilitated by government policies and legislation. Climate change is also contributing to the problem, with parts of Bolivia already turning into savannas. The Bolivian government, under President Luis Arce, has been criticized for its poor environmental record and lack of commitment to curbing deforestation, instead prioritizing economic growth and food security.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Deforestation rate | Third-highest in the world |

| Deforestation period | From 1976 to 2021, Bolivia lost 8.6 million hectares of forest |

| Deforestation rate in 2022 | Bolivia lost almost 400,000 hectares of primary forest |

| Deforestation causes | Fires, illegal deforestation, agricultural industry, cattle ranching, soy production, climate change |

| Deforestation enablers | Governmental policies, legislation, fund allocation, low taxation, cheap labour, corruption |

| Deforestation consequences | Loss of biodiversity, soil degradation, air-quality degradation, water shortages, contamination of water sources |

What You'll Learn

Governmental policies

The Bolivian government has implemented policies that actively encourage deforestation, allowing permits for cutting down trees in protected natural reserves and areas inhabited by indigenous communities. During his first mandate, Evo Morales, President of Bolivia from 2006 to 2019, amended the constitution to include the rights of Pachamama, the Bolivian term for Mother Earth, and granted clearly delineated territories and land-use rights to indigenous communities. However, in 2015, towards the end of Morales' first mandate, the government decided to shift its economic focus from oil and natural gas exports to agriculture. This shift in policy required access to territories previously occupied by forests and indigenous communities.

The Morales government passed numerous laws that facilitated industrial agriculture and deforestation, such as the law legalizing illegal deforestation prior to 2011, the 2015 law allowing the cutting of up to 20 hectares of forest on small community-owned plots, and the law setting a goal of tripling the country's livestock population. These policies have had detrimental effects, with Bolivia losing almost 400,000 hectares of primary forest in 2022, surpassing Indonesia in the rate of deforestation.

The current President, Luis Arce, has continued this trend, supporting the expansion of extractive industries and agricultural production. Arce's administration created the Bolivia Agricultural Production Company (EBPA) through Supreme Decree 4701, which allows for the use of public lands for agricultural purposes and emphasizes the marketing of products in international markets. Additionally, the Bolivian Ecological Oil Industry Productive Public Company (IBAE) was established to facilitate the expansion of biodiesel production, including palm oil, which will result in further deforestation of Amazonian forests.

At the international level, Bolivia has been reluctant to commit to concrete deforestation targets. It has avoided, obstructed, or rejected such targets and did not sign the Glasgow Leader's Declaration on Forests and Land Use at COP26 in 2021. Despite setting explicit deforestation targets through its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the upward trend in deforestation raises doubts about the feasibility of these targets.

Greetings in Bolivia: A Cultural Guide to Saludos

You may want to see also

Cattle ranching

The Bolivian government has been encouraging deforestation, allowing permits for cutting down trees in protected natural reserves and areas inhabited by indigenous communities. This has been facilitated by corruption, with thousands of hectares of land now owned by private interests, including farmers and cattle ranchers.

The demand for cattle ranching in Bolivia is driven by both domestic consumption and exports, particularly to China. Around 80% of Bolivian cattle are raised for domestic consumption, while the rest is exported.

To meet this demand, cattle ranchers clear land by chopping down trees and burning them. This has led to a loss of biodiversity, soil degradation, air and water quality degradation, and water shortages. It has also disrupted the lives of local indigenous communities, who depend on the forest for their survival.

To address the issue of deforestation caused by cattle ranching, experts recommend reducing the expansion of cattle ranching and enforcing existing legislation that protects carbon-rich forests. Intensifying cattle ranching by increasing the number of cattle per unit of pasture land could also help meet the demand for beef without further expanding into forests.

In addition, improving pasture management practices and promoting sustainable development goals can help reconcile cattle ranching with biodiversity and social inclusion objectives. This includes implementing rotational grazing, improving fire management, and recognizing indigenous land rights and participatory planning.

Bolivia Climbing: August's Late-Season Challenges

You may want to see also

Soy production

The Chiquitano forest, located in the east of the country, has been particularly affected by soy production. This unique dry tropical forest, known for its rich biodiversity, has become a deforestation hotspot in recent years. Between 2017 and 2022, thousands of hectares of the Chiquitano forest were cleared, with soy and cattle-ranching being the main drivers of this destruction.

The expansion of soy production in Bolivia is driven by a combination of factors, including the high global demand for soy, the profitability of the crop, and government policies promoting large-scale agriculture. Bolivian government policies have actively encouraged deforestation, with permits being granted to cut down trees in protected natural reserves and indigenous community areas. Additionally, the government has implemented legislation and fund allocation that facilitates deforestation.

The Bolivian government's promotion of large-scale agriculture has had devastating social and environmental impacts. Agribusiness-driven deforestation has resulted in wildlife habitat destruction, invasion of indigenous territories, and soil degradation. The loss of forest cover has also led to air and water quality degradation, water shortages, and contamination of water sources with fertilizers and pesticides.

The Mennonites, a religious group of extremely orthodox Protestants, have been identified as significant contributors to soy-driven deforestation in Bolivia. The Mennonites, who live in isolated communities and employ traditional farming methods, have been efficient in clearing forests and converting them into agricultural land. They have founded hundreds of communities across Latin America, and in Bolivia, they have been associated with the clearing of vast areas of forest, particularly in the Beni and Santa Cruz departments.

Another factor contributing to soy-driven deforestation in Bolivia is the involvement of multinational agricultural corporations. Cargill, one of the world's largest soy producers, has been implicated in the destruction of Bolivia's forests. Despite committing to achieving fully traceable and "deforestation-free" supply chains, Cargill has been linked to purchases from farms in Bolivia where deforestation has occurred.

In conclusion, soy production poses a significant threat to Bolivia's rainforests. The combination of global demand, government policies, and the activities of corporations and religious groups has resulted in widespread deforestation, with severe ecological and social consequences. Addressing this complex issue will require a multi-faceted approach that considers the economic, social, and environmental impacts of soy production in the country.

Bolivia's Night Skies: A Unique Perspective

You may want to see also

Climate change

Bolivia's rainforests are being hurt by climate change. From 1976 to 2021, Bolivia lost 8.6 million hectares of its forests, which is equivalent to 14% of its forests and the size of Austria. This loss has been facilitated by climate change, with parts of Bolivia already turning into savannahs.

The effects of climate change are exacerbating the traditional dry and hot weather in Bolivia, making it more challenging to control fires. Wildfires, mostly originating from land-clearing activities, scorched almost 600,000 hectares of land in eastern Bolivia between January and August 2021. The authorities reported that wildfires, mostly linked to land-clearing activities, had scorched 2.6 million hectares of land in Santa Cruz in the first ten months of 2021. The fires are fueled by increasingly dry and hot conditions, creating a vicious cycle of climate change fueling forest fires and vice versa.

The WWF states that to restrict the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius in line with the Paris Agreement, more action is needed to reduce carbon emissions from forest fires. Forest fires release vast amounts of planet-warming carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, with Bolivia emitting the equivalent of 192 million metric tons in 2020 alone. As greenhouse gas emissions and temperatures rise, dwindling green vegetation and water resources make fires more likely and intense.

The effects of climate change are already being felt on the ground in Bolivia. Residents of Santo Corazon, a settlement in San Matias, have reported longer and more frequent droughts, leading to water shortages. The fires are also taking a toll on the local wildlife, with reptiles like lizards and snakes being caught in the flames and intoxicated by smoke.

In addition, the Amazon Forest is nearing a tipping point, where it will be irreversibly turned into a dry and degraded savannah, and will become a source of greenhouse gases instead of a sinkhole. The Bolivian government's focus on agriculture and encouragement of deforestation are contributing to the climate crisis and pushing the country's forests closer to this tipping point.

Exploring Holy Week Traditions in Bolivia

You may want to see also

Illegal deforestation

The primary driver of illegal deforestation in Bolivia is the expansion of agricultural land, particularly for cattle ranching and soy production. Between 1992 and 2004, cattle ranching accounted for 27% of deforestation in the country. The situation is exacerbated by the Bolivian government's policies, which actively encourage deforestation. For example, the government has allowed permits for cutting down trees in protected natural reserves and indigenous community areas. Additionally, the government has passed laws that legalise illegal deforestation, such as the law permitting the cutting of up to 20 hectares of forest on community-owned plots.

The agricultural industry, centred in the province of Santa Cruz, is responsible for a significant portion of illegal deforestation. It is estimated that 83% of national deforestation has occurred in this region, with 74% of deforestation for agro-conversion purposes being illegal. The Bolivian government's creation of the Bolivia Agricultural Production Company (EBPA) through Supreme Decree 4701 has further bolstered this industry, allowing for the use of public lands and promoting the marketing of products in international markets.

The soy sector in Bolivia is a significant contributor to illegal deforestation. The expansion of soy plantations to meet growing demand for livestock feed has resulted in the clearing of vast areas of forest. In 2021, 31.8 hectares of native vegetation were cleared for every thousand tonnes of soy produced in Bolivia, a significantly higher rate than in neighbouring countries such as Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay. The Bolivian government has encouraged this expansion by increasing soy export quotas and changing land assignments to allow agriculture in certain forest areas.

The government's focus on economic development and the lack of pressure from consumers demanding deforestation-free products have hindered efforts to address illegal deforestation. Additionally, illegal deforestation is rarely penalised, and when fines are imposed, they are negligible compared to other countries. As a result, the prospects for action to end deforestation and transition to sustainable agriculture in Bolivia appear remote.

Exploring Bolivia's Lakes: A Natural Wonder

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Bolivian government's policies and legislation are actively encouraging deforestation, allowing permits for cutting down trees in protected natural reserves and areas inhabited by indigenous communities. The main driving force behind Bolivia’s forest loss is the proliferation of surfaces for cattle ranching and soy production.

From 1976 to 2021, Bolivia lost 8.6 million hectares of forest, which is equivalent to 14% of its forests. In 2022, Bolivia lost almost 400,000 hectares of primary forest.

The government has a poor environmental record, with President Luis Arce supporting the unbridled growth of a largely extractive economy and refusing to commit to deforestation targets. The creation of the Bolivia Agricultural Production Company (EBPA) and the Bolivian Ecological Oil Industry Productive Public Company (IBAE) will likely lead to further deforestation and the destruction of biodiversity.

Deforestation has led to soil degradation, water and air contamination, and the introduction of new pests. It has also resulted in the loss of biodiversity and the alteration of the lives of locals, as the forests are a key survival resource for indigenous communities.

International cooperation and pressure through multilateral organizations such as the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) could help. Brazil and Colombia, which face similar challenges, have enacted meaningful environmental policies and achieved significant reductions in deforestation, providing potential models for Bolivia to follow.