Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a state in the southeast of Germany. It is the largest German state by land area and the second most populous, with its capital, Munich, being the third-largest city in Germany.

Bavaria has a distinct culture, largely due to its Catholic heritage and conservative traditions, which includes a unique language, cuisine, architecture, festivals, and Alpine symbolism. It also has the second-largest economy among the German states by GDP figures, giving it the status of a wealthy German region.

During the Cold War, Bavaria was part of West Germany.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Official Name | Free State of Bavaria |

| Nickname | The Beer State |

| Abbreviation | BY |

| Time Zone | Central European Time (CET); Central European Summer Time (CEST) |

| Capital City | Munich |

| Population | 13.1 million |

| Area | 70,550 km² |

| Religion | 46.9% Catholic, 17.2% Evangelical Lutheran, 4% Muslim |

| Economy | Strong; second-largest among German states by GDP |

| Politics | Christian Social Union (CSU) |

What You'll Learn

The History of Bavaria

Early Settlements and Roman Raetia

There is evidence of Palaeolithic human settlements in Bavaria, but the earliest inhabitants known from surviving written sources were the Celts, who participated in the widespread La Tène culture. The Roman Empire under Augustus made the Danube, which runs through Bavaria, its northern boundary. What is now southern Bavaria was in the northern half of the Roman province of Raetia, which was the land of the Vindelici. The main Roman city was Augusta Vindelicorum, modern Augsburg.

Migrations and the Early Medieval Period

During the 5th century, the Romans in Raetia and Noricum, south of the Danube, came under increasing pressure from people north of the Danube. This area was considered by the Romans to be part of Germania. The name "Bavarian" (Latin Baiovarii) comes from the north of the Danube, outside the empire, and from the Celtic Boii, who lived there earlier. By the 6th century AD, some elements of the victorious Marcomanni people would help to form the Bavarii confederation, which incorporated Bohemia and Bavaria.

The Stem Duchy of Bavaria

Around 550 AD, the Bavarians came under the dominion of the Franks, who put the area under the administration of a duke. The first duke known was Garibald I, a member of the powerful Agilolfing family. This was the beginning of a series of Agilolfing dukes that lasted until 788 AD. For a century and a half, a succession of dukes resisted the inroads of the Slavs on their eastern frontier.

The Duchy During the Carolingian Period

Duchy During the Ottonian and Salian Periods

In 920 AD, Bavaria was ruled by Henry the Fowler of the Ottonian dynasty. Henry recognised Arnulf as duke, confirming his right to appoint bishops, coin money, and issue laws. A similar conflict took place between Arnulf's son and successor Eberhard and Henry's son Otto I the Great. Eberhard proved less successful than his father, and in 938 AD, he fled from Bavaria.

Geographic Fluctuations

During the years following the dissolution of the Carolingian Empire, the borders of Bavaria changed continuously. For a lengthy period after 955 AD, it finally started expanding. However, during the later years of the rule of the Welfs, a contrary tendency operated, and the extent of Bavaria shrank.

Under the Wittelsbach Dynasty

A new era began when, in 1180 AD, Emperor Frederick I awarded the duchy to Otto, a member of the old Bavarian family of Wittelsbach. The Wittelsbach dynasty ruled Bavaria without interruption until 1918 AD. When Otto of Wittelsbach gained Bavaria, the duchy's borders comprised the Böhmerwald, the Inn, the Alps, and the Lech; and the duke exercised practical power only over his extensive private domains.

Renaissance and Counter-Reformation

In the 16th century, Duke William IV followed the traditional Wittelsbach policy of opposition to the Habsburgs until 1534 when he made a treaty with Ferdinand, the king of Hungary and Bohemia. William also did much to secure Bavaria for Catholicism. The reformed doctrines had made considerable progress in the duchy when the duke obtained extensive rights over the bishoprics and monasteries from the pope. He then took measures to repress the reformers, many of whom were banished.

Electorate of Bavaria

In 1623, the Bavarian duke replaced his relative of the Palatinate branch, the Electorate of the Palatinate, in the early days of the Thirty Years' War. During the early and mid-18th century, the ambitions of the Bavarian prince electors led to several wars with Austria and occupations by Austrian forces.

Revolutionary and Napoleonic Periods

In 1792, French revolutionary armies overran the Palatinate, and in 1795 the French invaded Bavaria itself, advancing to Munich. Between the French and the Austrians, Bavaria was now in a vulnerable position. The new elector, Maximilian IV Joseph, succeeded to a difficult inheritance. On 2 December 1800, the Bavarian armies were involved in the Austrian defeat at Hohenlinden, and the French once more occupied Munich.

Constitution and Revolution

In 1818, the constitution was proclaimed. The parliament was to consist of two houses; the first comprising the great hereditary landowners, government officials, and nominees of the crown; the second, elected on a very narrow franchise, comprising representatives of the small landowners, the towns, and the peasants.

Bavaria During the Weimar Republic

Republican institutions replaced royal ones in Bavaria during the upheavals of November 1918. Provisional National Council Minister-President Kurt Eisner declared Bavaria to be a free state. Eisner was assassinated in February 1919, leading to a Communist revolt and the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic.

Bavaria During the Nazi Era

With the rise of the Nazis to power in 1933, the Bavarian parliament was dissolved without new elections. The NSDAP was declared the only legal party, and all other parties in Germany and Bavaria were dissolved. Bavaria itself was broken up during the reorganisation of the Reich. Instead of the states, Reichsgaue were established as administrative subdivisions.

Bavaria During the Federal Republic of Germany

Following the end of World War II, Bavaria was occupied by US forces, who reestablished the state on 19 September 1945. Bavaria lost its district on the Rhine, the Palatinate, in 1946. By September 1950, 2,155,000 expellees had found refuge in Bavaria, nearly 27% of the population. In the following decades, Sudeten Germans were acknowledged as Bavaria's fourth largest ethnic group, along with Bavarians, Franconians, and Swabians.

Exploring Ulm: Bavaria's Hidden Gem

You may want to see also

Bavarian Culture and Identity

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a state in the southeast of Germany. It is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total land area of Germany. Bavaria has a distinct culture, largely due to its Catholic heritage and conservative traditions, which includes a language, cuisine, architecture, festivals, and elements of Alpine symbolism.

Bavaria has a long and predominant tradition of Roman Catholic faith. Pope Benedict XVI was born in Marktl am Inn in Upper Bavaria and was Cardinal-Archbishop of Munich and Freising. However, the culturally Franconian and Swabian regions of the modern State of Bavaria are historically more diverse in religiosity, with both Catholic and Protestant traditions. As of 2020, 46.9% of Bavarians adhered to Catholicism, 17.2% to the Evangelical Lutheran Church, 3% were Orthodox, 4% were Muslim, and 31.9% were irreligious or adhered to other religions.

Bavarians commonly emphasize pride in their traditions. Traditional costumes collectively known as Tracht are worn on special occasions and include Lederhosen for males and Dirndl for females. Centuries-old folk music is performed, and the Maypole, or Maibaum, bears witness to the ancient Celtic and Germanic remnants of cultural heritage in the region. Bavarians tend to place a great value on food and drink. In addition to their renowned dishes, Bavarians also consume many items of food and drink that are unusual elsewhere in Germany, such as Weißwurst ("white sausage") and, in some instances, a variety of entrails. Bavarians are particularly proud of the traditional Reinheitsgebot, or beer purity law, initially established by the Duke of Bavaria in 1487. According to this law, only water, barley, and hops were allowed in beer. Bavarians are also known as some of the world's most prolific beer drinkers, with an average annual consumption of 170 liters per person.

Bavaria is also home to the Franconia wine region, which has produced wine (Frankenwein) for over 1,000 years and is famous for its use of the Bocksbeutel wine bottle. The production of wine forms an integral part of the regional culture, and many of its villages and cities hold their own wine festivals (Weinfeste) throughout the year.

Bavaria's versatility is reflected by its seven administrative districts, each of which has its own competencies when it comes to business, science, networks, and education. The variation in cultures and dialects (more than 60 dialects are spoken in Bavaria) gives each region a personal charm entirely of its own. Bavaria is also an increasingly cosmopolitan place, with 12% of its citizens being expatriates and Munich featuring one of the biggest communities of foreigners in Germany (28.5% of the population).

Bavaria's inhabitants are said to be charming, proud, self-confident, and usually sociable but sometimes stubborn. Grumbling is just part and parcel of everyday life. However, though maybe complaining about one’s own problems in life, Bavarians adopt a liberal motto of “to live and let live”. The state’s beautiful and often romantic scenery, with its lakes, mountains, and castles, as well as the region’s history, make Bavarians typically quite patriotic. Being proud of their origins, traditions are highly valued, celebrated, and often form the centrepiece of the social life of the community.

Exploring Dresden's Place in Germany's Cultural Landscape

You may want to see also

Bavaria's Political Culture

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a state in southeast Germany with a distinct culture, largely due to its Catholic heritage and conservative traditions. It is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the country's total land area, and the second most populous, with over 13 million inhabitants.

Bavaria has a multiparty system, but it has long been a bastion of conservative politics in Germany, with the Christian Social Union (CSU) winning every election since 1946. The CSU has almost a monopoly on power, with every Minister-President since 1957 being a member of the party. The CSU's power base is in the more rural and conservative areas of the state, while the bigger and more liberal cities, especially Munich, have been governed for decades by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).

In terms of political processes, Bavaria has a unicameral Landtag (state parliament), which is elected by universal suffrage for a period of five years. The state government, which consists of the Minister-President and up to 17 state ministers and secretaries, is the supreme executive authority. Bavaria also has a strong tradition of direct democracy at the local level, with citizens' initiatives leading to a high level of participation in communal and municipal affairs.

Freezing Bavarian Sauerkraut: Is It Possible?

You may want to see also

Bavaria's Religious Traditions

Bavaria has a distinct culture, largely due to its Catholic heritage and conservative traditions. The state has a rich religious history, with a long and predominant tradition of Roman Catholicism. In 1970, Roman Catholicism was the religion of 69.9% of the population in Old Bavaria, while the Evangelical (Lutheran) church was the predominant religion in Franconia, comprising 25.7% of the population. Both religions are officially recognised and supported by the state.

Bavaria was one of the centres of the Old Catholic movement, a schism resulting from the papacy's stand on infallibility in the 1870s. Religious festivals have always been an integral part of life in Old Bavaria, with church dedication, or Kirchweih, being a significant three-day harvest festival. Fasching, the Bavarian version of carnival, begins in early January and continues until the day before Ash Wednesday. In addition to the regular church holidays, the patron saints of markets, artisan groups, and other organisations are also honoured. Even today, Bavaria has 14 official holidays, more than any other German state.

Bavarian Catholics tend to be more regular in church attendance than their Protestant neighbours. However, like many Roman Catholic countries, there is a serious shortage of priests, resulting in a growing lay ministry.

Bavarian folk costumes, or Trachten, are worn for both formal and informal occasions. The woman's Dirndl is a tight-bodiced, full-skirted outfit worn with a contrasting white blouse and apron, while Lederhosen are leather shorts for men. Folk music is played on traditional instruments such as the Hackbrett, the zither, and the folk harp, or sung by soloists or groups. Folk dancing, especially the Schuhplattler, is also popular, and many communes have groups devoted to various aspects of folk culture.

A lively folk literature consisting of stories and poetry in dialect is regularly featured in local newspapers, books, and television.

Gelsenkirchen and Bavaria: Are They Connected?

You may want to see also

Bavaria's Economy

Bavaria has one of the largest economies in Germany and Europe. Its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2007 exceeded €434 billion (about $600 billion). The GDP of the region increased to €617.1 billion in 2018, accounting for 18.5% of German economic output.

Agriculture and forestry account for about 10% of the state's economic output. Wheat, barley, sugar beets, and dairy goods are the leading products.

Bavaria has the best-developed industry in Germany and the lowest unemployment rate at 2.9% as of October 2021. The state has strong economic ties with Austria, the Czech Republic, Switzerland, and Northern Italy.

The Free State of Bavaria, which used to be an agricultural state only 50 years ago, has now become "Europe's high-tech Mecca", according to Microsoft's Bill Gates. The region is characterised by a tight network of small and medium-sized industrial companies, trading and service businesses.

Bavaria leads nationally and internationally in almost all new sectors of technology, from information and communication technology to biotechnology, gene technology, energy, and environmental technology. The state is an attractive region for high-tech companies, and service is a top priority.

The state government has reinvested billions of euros from privatisation into the modernisation of the economy, state, and society. This has boosted Bavaria's competence in future technology areas such as information and communication technology (ICT), life sciences, new materials, mechatronics, energy, and environmental technology, as well as nanotechnology.

Leavenworth: A Bavarian Town in Washington State

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Bavaria is in West Germany.

Bavaria is a state in the southeast of Germany.

The capital of Bavaria is Munich.

The official name of Bavaria is the Free State of Bavaria.

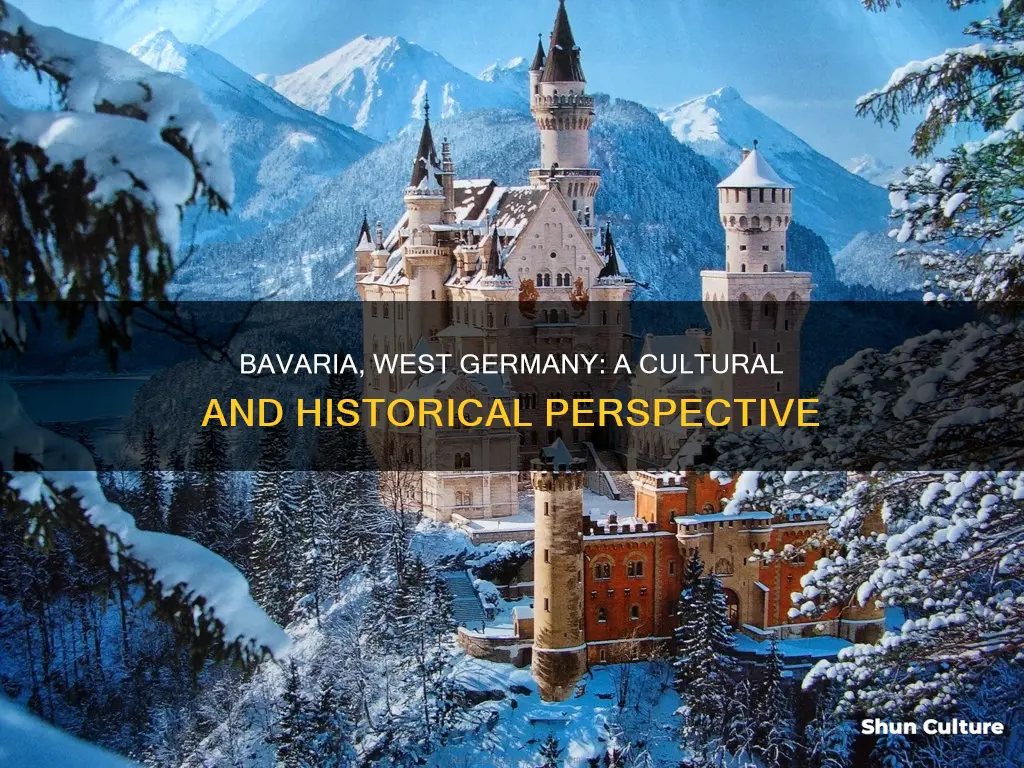

Some famous landmarks in Bavaria include the Neuschwanstein Castle, the Marienplatz, and the Zugspitze mountain.