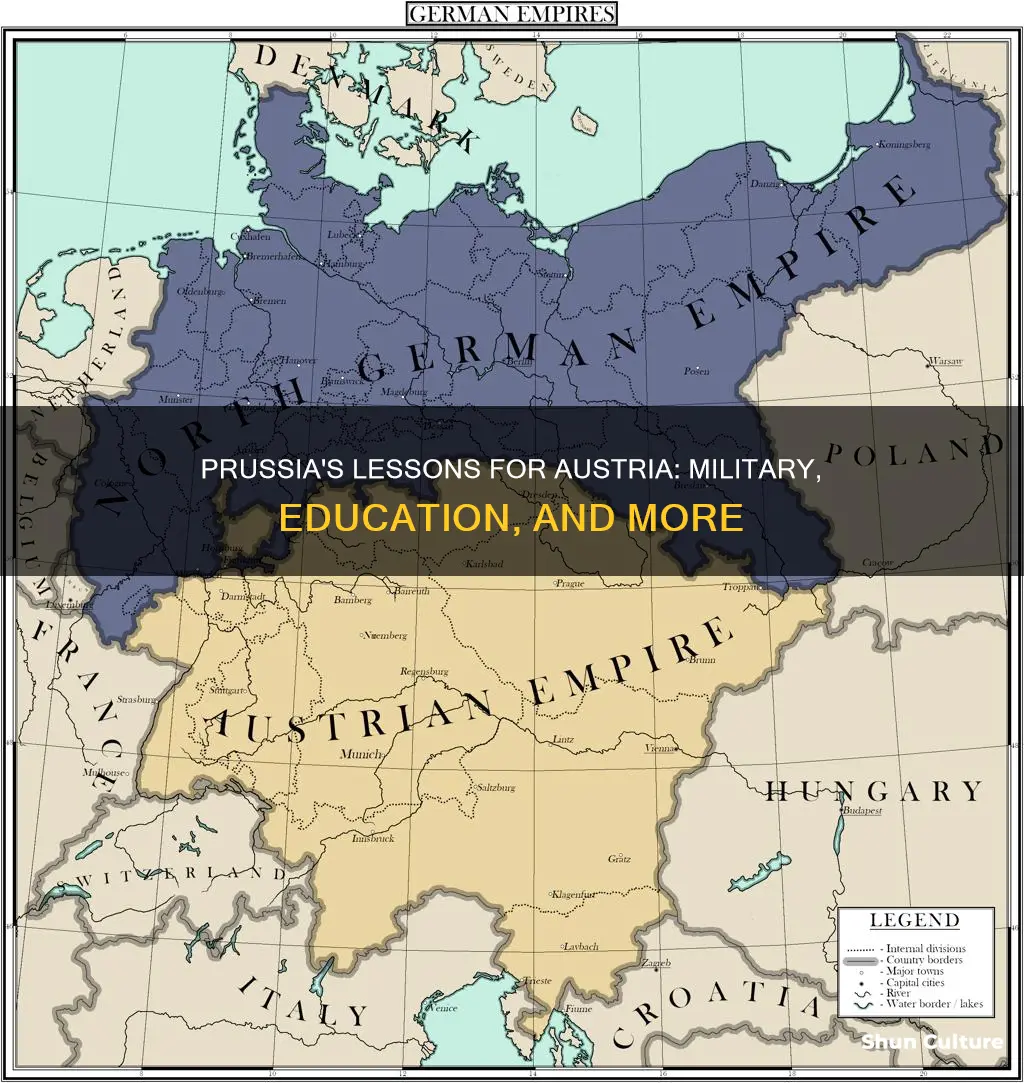

The rivalry between Prussia and Austria was an important element of the German question in the 19th century. Both were the most powerful German states in the Holy Roman Empire by the 18th and 19th centuries and had engaged in a struggle for supremacy among smaller German states. The rivalry was characterised by major territorial conflicts and economic, cultural, and political aspects. Prussia was the most powerful and militaristic of the German states in the mid-19th century. The ruling families of Austria and Prussia, the Habsburgs and the Hohenzollerns, both wanted supremacy in central Europe.

Prussia was a kingdom ruled by the Hohenzollern family, while Austria was ruled by Emperors of the Habsburg dynasty. Although Austria had been the leading power in Central Europe for some time, Prussia was a state on the rise, growing in wealth and military strength. It had conscription for its army, meaning there was always a force of well-trained soldiers, and could arm itself with the latest in modern weaponry. Prussia also had a more extensive and modernised railway system.

Prussia and Austria first met in the Silesian Wars and Seven Years' War during the middle 18th century until the conflict's culmination in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. The German term is Deutscher Dualismus (literally German dualism), which does not cover only rivalry but also cooperation, for example, in the Napoleonic Wars. Indeed, both powers did jointly dominate the German Confederation, which functioned only in times of cooperation.

Prussia wanted to make Prussia dominant in any German Empire that was to exist. Austria was a multi-national, multi-ethnic empire, which would give a new Germany more territory, but would dilute the 'Germaness' of it. The state would be divided between two powerful noble houses, the Habsburgs and the Hohenzollerns, which would probably lead to some interesting power struggles. Prussia was industrialising far more rapidly than Austria, and would likely have had to spread money around in any 'Grossdeutschland' Empire in order for them to industrialise at a similar rate.

What You'll Learn

Superior Prussian military training and weaponry

Prussia's military training and weaponry were superior to Austria's in several ways.

Firstly, Prussia had implemented universal conscription, meaning that all Prussian citizens were liable to conscription and the active-duty army was larger. Prussia also had a reserve army equal in size to the army that Helmuth von Moltke deployed against Austria. In contrast, the Austrian army routinely dismissed infantry conscripts to their homes on permanent leave soon after their induction, retaining only a cadre of long-term soldiers for formal parades and routine duties. Austrian conscripts had to be trained almost from scratch when they were recalled to their units on the outbreak of war.

Secondly, the Prussian army was locally based, organised in Kreise (military districts), with most reservists living close to their regimental depots. This enabled the rapid mobilisation of troops. In contrast, Austrian policy was to ensure that units were stationed far from home to prevent them from taking part in separatist revolts. Conscripts on leave or reservists recalled to their units during mobilisation faced a journey that might take weeks before they could report for duty, making the Austrian mobilisation much slower than that of the Prussian Army.

Thirdly, Prussia's railway system was more extensively developed than Austria's, which allowed for the rapid movement of troops within friendly territory. Moltke, the Prussian Chief of General Staff, stated:

> "We have the inestimable advantage of being able to carry our Field Army of 285,000 men over five railway lines and of virtually concentrating them in twenty-five days... ... Austria has only one railway line and it will take her forty-five days to assemble 200,000 men."

Fourthly, the Prussian infantry were equipped with the Dreyse needle gun, a bolt-action rifle which could be fired and reloaded much faster than the muzzle-loading Lorenz rifles of the Austrian army. The Austrian rifles also needed to be reloaded from a standing position, leaving them exposed during the reloading process.

Fifthly, Prussia had replaced up to 60% of their smoothbore artillery with the technologically superior C64 (field gun), which had been in production since 1859.

Sixthly, the Prussian generals realised that they needed to explore new military tactics to stay ahead of the Austrians. They sent officers to observe the American Civil War, who then briefed their generals about the new tactics they had observed.

Austria-Hungary's War Declaration on Serbia: Why?

You may want to see also

The role of Otto von Bismarck

Otto von Bismarck was a Prussian statesman and diplomat who played a crucial role in the unification of Germany. Bismarck's Realpolitik and firm governance earned him the nickname "The Iron Chancellor". Bismarck's role in the unification of Germany began in 1862 when he was appointed Minister President of Prussia by King Wilhelm I. Bismarck's leadership of Prussia was marked by three short, decisive wars against Denmark, Austria, and France.

The War Against Denmark

Bismarck provoked the Second Schleswig War against Denmark by insisting that the territories of Schleswig and Holstein legally belonged to the Danish monarch under the London Protocol. However, he also denounced Christian IX's decision to completely annex Schleswig to Denmark. With support from Austria, Bismarck issued an ultimatum for Christian IX to return Schleswig to its former status, which Denmark refused, leading to war. Denmark ultimately renounced its claim on both duchies, and Bismarck used a series of unworkable demands to remove Augustenburg, the Danish duke, from power.

The War Against Austria

In 1865, Bismarck made an alliance with Austria, signing the Gastein Convention, under which Prussia received Schleswig, while Austria received Holstein. However, in 1866, Austria reneged on the agreement and demanded that the Diet determine the Schleswig–Holstein issue. Bismarck used this as an excuse to start a war with Austria, provoking them by occupying Holstein. Bismarck also made a secret alliance with Italy, who desired Austrian-controlled Veneto, forcing the Austrians to divide their forces. Prussia ultimately won the decisive Battle of Königgrätz, and Bismarck insisted on a "soft peace" with no annexations and no victory parades to be able to quickly restore friendly relations with Austria.

The War Against France

Bismarck's victory over Austria increased tensions with France, as Emperor Napoleon III tried to gain territory for France as compensation for not joining the war against Prussia. Bismarck deliberately provoked a French attack by publishing the Ems Dispatch, a carefully edited version of a conversation between King Wilhelm and the French ambassador, Count Benedetti, inflaming popular sentiment on both sides in favour of war. France mobilised and declared war, and the German states, swept up by nationalism and patriotic zeal, rallied to Prussia's side. Prussia won a series of swift victories, and Napoleon III was captured. Following the Siege of Paris, the German princes proclaimed the founding of the German Empire in 1871 at Versailles, uniting all scattered parts of Germany except Austria.

The Austrian Legacy of Swarovski Crystals

You may want to see also

The rivalry's culmination in the Austro-Prussian War

The rivalry between Prussia and Austria culminated in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, also known as the German War or the Seven Weeks' War. This conflict was the result of a dispute between the two powers over the administration of Schleswig-Holstein, which they had conquered from Denmark and agreed to jointly occupy at the end of the Second Schleswig War in 1864. The crisis began on 26 January 1866, when Prussia protested against the decision of the Austrian Governor of Holstein to allow the estates of the duchies to call up a united assembly, claiming that this breached the principle of joint sovereignty. Austria responded on 7 February, asserting that its decision did not infringe on Prussia's rights. In March, Austria reinforced its troops along its frontier with Prussia, leading to a partial mobilisation of five divisions by Prussia on 28 March.

Prussia, led by Minister President Otto von Bismarck, formed an alliance with Italy on 8 April, committing it to the war if Prussia entered into one against Austria within three months. This incentivised Bismarck to go to war with Austria within that timeframe so that Italy would divert Austrian strength away from Prussia. Austria responded by mobilising its Southern Army on the Italian border on 21 April, with Italy declaring war on Austria on 20 June. Prussia also formed alliances with various German states, including Oldenburg, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, and Brunswick.

On 15 June, Prussia invaded Hanover, Saxony, and the Electorate of Hesse. The main campaign of the war occurred in Bohemia, where the Prussian armies, led by King William I, converged and met the Austrian army at the Battle of Königgrätz on 3 July. The Prussian victory at Königgrätz was near-total, with Austrian battle deaths nearly seven times the Prussian figure. An armistice between the two powers came into effect at noon on 22 July, and a preliminary peace was signed on 26 July.

The war resulted in a shift in power among the German states away from Austrian and towards Prussian hegemony. It led to the abolition of the German Confederation and its partial replacement by the unification of all the northern German states in the North German Confederation, which excluded Austria and the other southern German states. The war also resulted in the Italian annexation of the Austrian realm of Venetia. Prussia's victory in the Austro-Prussian War confirmed its dominance over the German states and marked the culmination of its rivalry with Austria.

Austria's Invasion of Serbia: Mourning Franz's Death

You may want to see also

The impact of the war on the unification of Germany

The Austro-Prussian War of 1866 was a conflict between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia, with both sides aided by various allies within the German Confederation. The war was part of the wider rivalry between Austria and Prussia and resulted in Prussian dominance over the German states.

The major result of the war was a shift in power among the German states away from Austrian and towards Prussian hegemony. It resulted in the abolition of the German Confederation and its partial replacement by the unification of all of the northern German states in the North German Confederation that excluded Austria and the other southern German states. The war also resulted in the Italian annexation of the Austrian realm of Venetia.

The war erupted as a result of the dispute between Prussia and Austria over the administration of Schleswig-Holstein, which the two of them had conquered from Denmark and agreed to jointly occupy at the end of the Second Schleswig War in 1864. The crisis started on 26 January 1866, when Prussia protested the decision of the Austrian Governor of Holstein to permit the estates of the duchies to call up a united assembly, declaring the Austrian decision a breach of the principle of joint sovereignty. Austria replied on 7 February, asserting that its decision did not infringe on Prussia's rights in the duchies. In March 1866, Austria reinforced its troops along its frontier with Prussia. Prussia responded with a partial mobilisation of five divisions on 28 March.

The Prussian Minister President Otto von Bismarck made an alliance with Italy on 8 April, committing it to the war if Prussia entered one against Austria within three months, which was an obvious incentive for Bismarck to go to war with Austria within three months so that Italy would divert Austrian strength away from Prussia. Austria responded with a mobilisation of its Southern Army on the Italian border on 21 April. Italy called for a general mobilisation on 26 April and Austria ordered its own general mobilisation the next day. Prussia's general mobilisation orders were signed in steps on 3, 5, 7, 8, 10 and 12 May.

When Austria brought the Schleswig-Holstein dispute before the German Diet on 1 June and also decided on 5 June to convene the Diet of Holstein on 11 June, Prussia declared that the Gastein Convention of 14 August 1865 had thereby been nullified and invaded Holstein on 9 June. When the German Diet responded by voting for a partial mobilisation against Prussia on 14 June, Bismarck claimed that the German Confederation had ended. The Prussian Army invaded Hanover, Saxony and the Electorate of Hesse on 15 June. Italy declared war on Austria on 20 June.

The war was a decisive victory for Prussia, which subsequently formed the North German Confederation, a military alliance de facto dominated by Prussia. This was the first step towards German unification, which was achieved in 1871 with the Franco-Prussian War.

Exploring Austria and Bratislava by Train and Foot

You may want to see also

The decline of the Austrian Habsburgs

The Austrian Habsburgs, also known as the House of Austria, were one of the most prominent and important dynasties in European history. They ruled until 1918, when the dynasty came to an end with the fall of the Habsburg monarchy and the deposition of the last Habsburg ruler, Charles I of Austria.

Military Defeats

The Austrian Habsburgs suffered several significant military defeats that weakened their position. In 1866, they were defeated by the Kingdom of Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War, resulting in the loss of Venetia and the exclusion of Austria from German affairs. This shift in power among the German states towards Prussian hegemony left Austria vulnerable.

Additionally, during the First World War, the Habsburg lands faced severe food shortages, and social unrest grew as the war dragged on. Mutinies broke out in the army and navy, further destabilizing the empire.

Rising Nationalism

The rise of nationalism in the 19th century posed a significant challenge to the multi-ethnic Habsburg Monarchy. The empire encompassed various nationalities, including Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Croats, Serbs, Romanians, and Italians, each with their own aspirations for self-determination. This internal division weakened the monarchy and made it difficult for the Habsburgs to maintain control.

Internal Power Struggles

Internal power struggles within the Habsburg dynasty also contributed to their decline. Emperor Franz Joseph, who ruled from 1848 to 1916, faced opposition from nationalist movements and made concessions to the Hungarians, leading to the formation of Austria-Hungary in 1867. This dual monarchy further strained the empire's unity and governance.

World War I and its Aftermath

World War I dealt a devastating blow to the Austrian Habsburgs. The empire suffered heavy casualties and territorial losses, and the war effort strained its economy. The end of the war in 1918 brought about the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy, as national councils were established in all provinces, declaring independence and dissolving the empire from within.

On November 11, 1918, Charles I of Austria issued a proclamation renouncing his rights to exercise political authority, marking the formal dissolution of the Habsburg Monarchy. The new republican Austrian government banished the Habsburgs from Austrian territory, and they were also deposed in Hungary, bringing an end to their rule.

Celebrating Christmas in Austria: Traditions and Customs

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Austro-Prussian War was fought in 1866 between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia was aided by the Kingdom of Italy, linking the conflict to the Third Independence War of Italian unification. The war resulted in Prussian dominance over the German states.

Prussia and the Austrian Empire had invaded the Danish territories of Schleswig and Holstein in 1864. However, by 1866, they were disagreeing over how to rule the captured lands. Prussia saw the dispute as an opportunity to become the dominant power in the German Confederation and began preparing for war with Austria.

The war resulted in the abolition of the German Confederation and its partial replacement by the unification of all of the northern German states in the North German Confederation, excluding Austria and the other southern German states. The war also resulted in the Italian annexation of the Austrian realm of Venetia.

The Battle of Nachod on 27 June 1866 was the first major clash of the war and resulted in the Prussian Second Army securing a mountain pass to reach Austrian territory. The decisive battle was fought on 3 July 1866 at Königgrätz and was won by the Prussians despite early Austrian success with artillery.