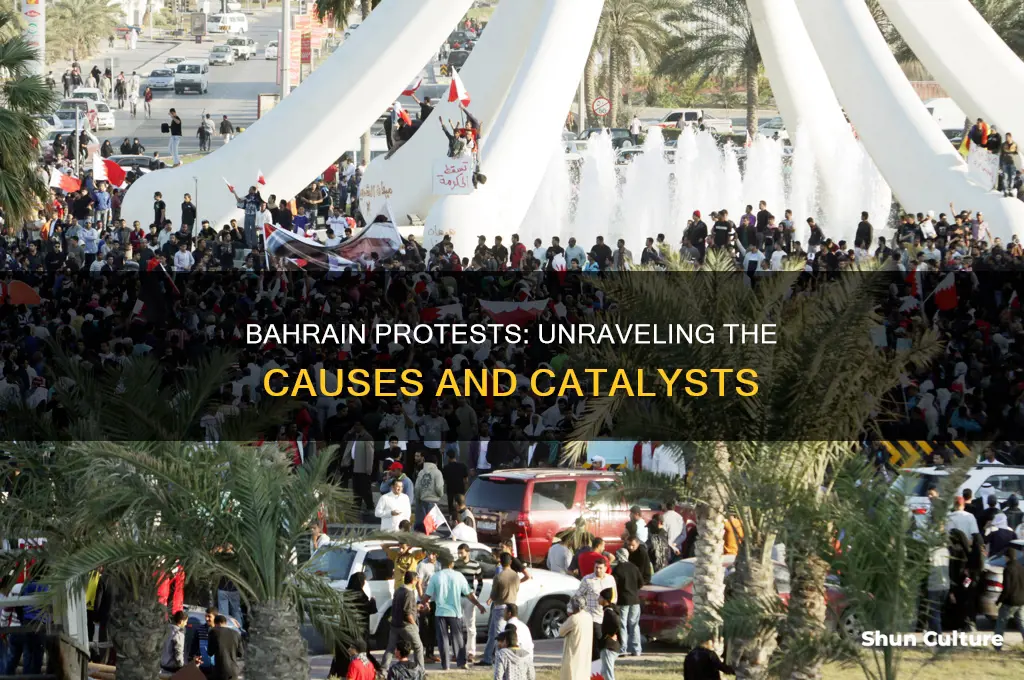

The 2011 uprising in Bahrain was a series of anti-government protests led by the Shia-dominant and some Sunni minority Bahraini opposition. The protests were inspired by the 2011 Arab Spring and demonstrations in Tunisia and Egypt.

The protests in Bahrain were a series of demonstrations, amounting to a sustained campaign of non-violent civil disobedience and some violent resistance. The protesters were initially demanding greater political freedom and equality for the 70% Shia population. This expanded to a call to end the monarchy of Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa following a deadly night raid on 17 February 2011 against protesters at the Pearl Roundabout in the capital Manama, known locally as Bloody Thursday.

The government responded with force, and the protests were crushed with the support of the Gulf Cooperation Council and Peninsula Shield Force. A state of emergency was declared on 15 March 2011, and martial law was imposed.

The roots of the uprising date back to the beginning of the 20th century, with Bahrainis sporadically protesting throughout the decades demanding social, economic and political rights.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date | February 14, 2011 |

| Location | Manama, Bahrain |

| Protesters | Thousands of Bahraini Shiites |

| Demands | Government reforms, resignation of Prime Minister Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa |

| Deaths | 1 |

| Injuries | Several |

| Police Action | Tear gas, rubber bullets |

What You'll Learn

- The 2011 uprising was inspired by the Arab Spring

- The Bahraini government used lethal force to suppress the protests

- The Gulf Cooperation Council sent troops to help contain the unrest

- The crackdown on protests continued after the state of emergency was lifted

- The Bahraini government continues to suppress dissent

The 2011 uprising was inspired by the Arab Spring

The 2011 uprising in Bahrain was inspired by the Arab Spring, a series of anti-government protests, uprisings, and rebellions that spread across the Arab world in the early 2010s. The Arab Spring began in Tunisia in December 2010, when a young street vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, set himself on fire to protest his treatment by local officials. This act catalysed a wave of pro-democracy protests that toppled several authoritarian regimes in the region.

The Bahraini uprising was part of this wave of protests. It began on February 14, 2011, as an "anti-government 'Day of Rage'" inspired by the successful uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia. One protester was killed, and the next day, another person died in clashes with police at the protester's funeral. On February 17, security forces raided the Pearl Roundabout, the focal point of the protests, killing four people. This marked a turning point, as some protesters began to call for an end to the monarchy.

The Bahraini protests were largely peaceful, but they were met with violent repression by security forces. The government crackdown was aided by a Gulf Cooperation Council security force composed of about 1,000 soldiers from Saudi Arabia and 500 police officers from the United Arab Emirates. Dozens of protest leaders were imprisoned, hundreds of Shi'ite workers were fired, and dozens of Shi'ite mosques were demolished. An independent investigation into the uprising, commissioned by the Bahraini government, concluded that excessive force and torture had been used against protesters.

The Arab Spring protests in Bahrain, like those in other countries, were driven by dissatisfaction with authoritarian rule, corruption, economic grievances, and political and human rights violations. They were also fuelled by new media technologies, with social media platforms playing a key role in mobilising protesters and spreading awareness.

Exploring Bahrain: Understanding Its Administrative Divisions

You may want to see also

The Bahraini government used lethal force to suppress the protests

On February 19, authorities ordered security and military forces to withdraw, and protesters reoccupied the Pearl Roundabout. However, on March 16, security and military forces forcibly cleared the Pearl Roundabout, killing at least six people, including two police officers. The Bahraini government's use of lethal force resulted in the deaths of more than 40 people, including four who died in custody from torture or medical neglect.

The Bahraini security forces' tactics included the use of birdshot pellets, rubber bullets, tear gas, and live ammunition, which caused most of the deaths and injuries of protesters and bystanders. The crackdown on protests also included arbitrary arrests and detentions, with over 1,600 people arrested for participating in or supporting the anti-government demonstrations. The Bahraini government's response to the protests was met with international condemnation and led to the establishment of the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry to investigate the events.

Bahrain's Turbulent Times: War or Peace?

You may want to see also

The Gulf Cooperation Council sent troops to help contain the unrest

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) sent troops to Bahrain to help contain the civil unrest that was taking place in the country. On March 14, 2011, the GCC announced that it would send troops, mainly from Saudi Arabia, to help contain the unrest. The following day, King Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa declared martial law. Government troops surrounded Shiite neighbourhoods and forcibly emptied the Pearl Roundabout, a major landmark in the capital of Manama, with tanks and machine guns. Naval ships from Kuwait also entered Bahrain.

The crackdown on protesters was brutal. The Bahraini government forces, with the support of the GCC troops, used tear gas, rubber bullets, and tanks to disperse the protesters. The crackdown resulted in the deaths of several protesters and bystanders, with security forces using birdshot pellets, rubber bullets, and live ammunition. The crackdown also led to mass arrests, with over 1,600 people detained for participating in or supporting the anti-government demonstrations.

The GCC's intervention marked the first time an Arab government requested foreign help during the Arab Spring. The opposition reacted strongly, calling it an occupation and a declaration of war, and pleaded for international help. The intervention also drew criticism from human rights groups, which documented the use of excessive force and torture by the security forces.

Bahrain's TV Testing: What's the Deal?

You may want to see also

The crackdown on protests continued after the state of emergency was lifted

On June 6, 47 doctors and nurses were tried for attempting to overthrow the monarchy by participating in protests and denying service to Sunni patients. On the same day, Shiites marched to protest the monarchy in several Manama suburbs; police broke up the gatherings with tear gas, rubber bullets, and birdshot.

On June 8, the government accepted a UN mission to investigate alleged human rights violations. Throughout June and August, thousands of Shiites protested in Manama and its suburbs every Friday.

On June 22, a special military court convicted 21 activists for conspiring to overthrow the government. Eight received life imprisonment sentences, including prominent activist Hassan Mushaima. Protests resulting from the verdicts were broken up by police with tear gas.

On June 28, Saudi Arabia announced it would withdraw most of its troops from Bahrain. The next day, King Hamad announced an independent investigation into human rights abuses against protesters.

On July 2, the National Dialogue began, but on July 12, Al Wefaq's representatives walked out after a Sunni representative condemned Shiite ideology. On July 19, National Dialogue participants reached a consensus, allowing parliament to reject the Prime Minister's cabinet choices.

On August 8, the Cabinet increased public sector salaries and monthly pensions and raised the debt ceiling to pay for National Dialogue initiatives. On August 12, Al Wefaq announced it would boycott the elections.

On August 25 and 26, police and protesters clashed after Shiite religious ceremony Quds Day was banned and prominent Shiite cleric Sheikh Isa Qassim told his supporters to boycott the elections. On August 31, a 14-year-old was killed when he was hit by a tear gas canister during anti-government protests in Sitra, a Shiite suburb of Manama. Thousands protested his death the next day.

On September 20, King Hamad created the National Compensation and Redress Fund to compensate those who sustained physical or material damage during the protests.

On September 24, parliamentary elections took place with a 17.4% turnout. Security forces prevented hundreds of Shiite protesters from reaching Pearl Roundabout.

On October 11, four editors of the independent newspaper Al Wasat were fined for publishing stories about anti-regime protests.

On November 23, an independent study commissioned by the king found that state forces used "excessive force" and torture against protesters. Just before the publication, protesters gathered, and police fired tear gas, killing one. The king promised reforms and created a National Commission to implement the suggestions.

On December 2, a British former police assistant commissioner and the former Miami police chief were hired to reform the police force. On December 23, police attacked Al Wefaq's headquarters with rubber bullets and tear gas after the group defied a protest ban.

On January 1, 2012, the Chief of Public Security announced that 500 officers would be recruited from all sections of Bahraini society to improve community relations, and they would only police the areas they were from. On January 15, the king gave Parliament the power to approve or withdraw confidence from Cabinets and to question ministers, and he increased salaries for private sector workers making less than 250 dinars per month.

On January 25, several people were wounded as protesters responded to Sheikh Qassim's call to "crush" security forces if they hurt women. Protesters attacked police in several Shiite villages.

From February 9 to May 28, 2012, jailed activist Abdulhadi al-Khawaja went on a hunger strike in anticipation of the first anniversary of the protests. Thousands rallied for his release about once a week until he ended his strike on May 28.

From February 11 to 14, hundreds protested in Manama to commemorate the uprising's first anniversary. Large sections of Manama were sealed off on the 14th, with little commotion in the city centre.

On March 15 and 16, 2012, police and protesters clashed in Shiite villages and Manama on the anniversary of the 2011 government crackdown.

On March 18, 2012, the government issued a code of conduct requiring police to follow ten guidelines for respecting human rights and codifying a zero-tolerance policy on torture.

On April 13, 2012, after the Grand Prix's CEO announced that the race would continue, thousands protested in Manama against the race. From April 15 to 22, 2012, Al Wefaq held daily protests against the Grand Prix. At least 60 Shiite activists were arrested.

On April 22, 2012, the Grand Prix took place. One man was killed by birdshot after clashing with police after the race. Clashes with police followed his funeral the next day.

On May 3, 2012, the king ratified constitutional reforms allowing Parliament to question and remove ministers and withdraw confidence in the Cabinet. Al Wefaq said the reforms were insufficient.

On May 5, 2012, activist Nabeel Rajab was arrested for inciting protests through social networking sites. He was released but arrested again on June 6 and sentenced to three months in prison. On June 8, tens of thousands protested against his arrest in western Manama.

On June 26, 2012, the government announced it would pay $2.6 million to families of protesters killed in 2011.

Disney Plus in Bahrain: Availability and Accessibility

You may want to see also

The Bahraini government continues to suppress dissent

The Bahraini government has a history of suppressing dissent, and this repression has continued in recent years. Since mid-2016, the Bahraini authorities have dramatically escalated their crackdown on critics, with a particular focus on human rights defenders, lawyers, journalists, political activists, Shia clerics, and peaceful protesters. The government has used a range of tactics to suppress dissent, including arbitrary detention, torture, threats, prosecution, imprisonment, and violence.

One prominent target of the Bahraini government's repression is Nabeel Rajab, the president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights. Rajab has been imprisoned multiple times and is currently serving a two-year sentence for media interviews and tweets. He also faces an additional 15-year sentence for his social media activity.

The Bahraini authorities have also targeted the independent newspaper Al-Wasat, suspending its online edition and later shutting it down entirely. The government has also dissolved Al-Wefaq, the main opposition group, and Waad, a secular opposition political party, on unfounded charges.

The Bahraini security forces, including the National Security Agency (NSA), have used excessive force to break up protests, beating protesters, firing shotguns and semi-automatic rifles, and using tear gas and armoured vehicles. Since the beginning of 2017, security forces have killed at least six people, including one child, and injured hundreds.

The international community, particularly the UK and the US, has been accused of remaining silent or toning down their criticism of Bahrain's human rights record. This silence has been seen as a green light for the Bahraini government to continue its repression of dissent.

The Bahraini government's suppression of dissent has had a chilling effect on civil society, with many peaceful critics feeling that the risks of expressing their views have become too high. The government's tactics have effectively crushed what was once a thriving civil society in Bahrain.

The Bahraini government's actions have been widely condemned by human rights organisations such as Amnesty International, which has called on the authorities to cease their crackdown on freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly, release prisoners of conscience, halt reprisals against human rights defenders, and ensure prompt and independent investigations into allegations of abuses.

Sonal: A Common Name in Bahrain?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The 2011 Bahrain protests were a series of anti-government demonstrations inspired by the 2011 Arab Spring and protests in Tunisia and Egypt. The protesters were mainly from the country's Shi'ite majority, who felt ignored by the minority Sunni government.

The protests began on 14 February 2011, with a "Day of Rage" in Manama, during which one protester was killed. The next day, another person died during clashes with police at the protester's funeral. On 17 February, police cleared the Pearl Roundabout, a focal point of the protests, killing four people. On 14 March, Gulf Cooperation Council troops, mainly from Saudi Arabia, were deployed to help contain the unrest. On 15 March, the King of Bahrain declared martial law, and security forces cracked down on protesters.

The protests were violently suppressed by security forces, with dozens of protesters being killed and thousands arrested. An independent commission, convened by the King, later concluded that excessive force and torture had been used against protesters. In the years following the protests, the Bahraini government continued to clamp down on opposition groups, and the country remains less free than it was before the 2011 protests.