The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a dual monarchy formed in 1867 by a compromise agreement between Vienna and Budapest. It was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe, geographically the second-largest country in Europe and the third-most populous worldwide. The empire was overseen by a central government responsible for matters of foreign policy, military command and joint finance, with the emperor as both head of state and government. The emperor was first crowned as king of both Austria and Hungary, with each kingdom retaining a degree of autonomy, its own parliament, prime minister, cabinet and domestic self-government. The official name of the state was the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, though in international relations, Austria-Hungary was used.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Official Name | Austro-Hungarian Monarchy |

| Alternative Names | Österreich-Ungarn, Österreichisch-Ungarische Monarchie, Österreichisch-Ungarisches Reich, Austro-Hungarian Empire, Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Doppelmonarchie, Dual Monarchy, Ausztria-Magyarország, k. u. k. Monarchie, Kaiserliche und königliche Monarchie Österreich-Ungarn, Császári és Királyi Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia, Danubian Monarchy, Donaumonarchie, Dual-Monarchie, Der Doppel-Adler, Kétsas |

| Years of Existence | 1867-1918 |

| Type of State | Multi-national constitutional monarchy |

| Geography | Second-largest country in Europe |

| Population | Third-most populous country in Europe and among the ten most populous countries worldwide |

| Industries | Fourth-largest machine-building industry in the world |

| Sovereign States | Two (The Empire of Austria and the Kingdom of Hungary) |

| Monarch | Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary |

| Number of Ethno-Language Groups | 11 |

| Examples of Ethno-Language Groups | Germans, Hungarians, Polish, Czech, Ukrainian, Slovak, Slovene, Croatians, Serbs, Italians and Romanians |

| Central Government | Responsible for matters of foreign policy, military command and joint finance |

What You'll Learn

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a dual monarchy

The central government of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was responsible for matters of foreign policy, military command and joint finance. It was comprised of the emperor, both prime ministers, three appointed ministers, members of the aristocracy and representatives of the military.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a relatively young nation-state, but it was a major European power in the years prior to World War I. It was the second-largest nation in Europe by territory and the third-largest by population, and it was rapidly modernising. The empire extended from the mountainous Tyrol region north of Italy to the fertile plains of Ukraine and the Transylvanian mountains of eastern Europe. It was home to a rich mix of people and cultures, with 11 major ethno-language groups.

The origins of the empire as two separate kingdoms led to a complex and unusual political organisation. There were often jealousies, grievances and disagreements between the two halves of the empire. The two kingdoms had their own armies, which were better funded and equipped than the imperial army. The imperial army faced considerable communication problems due to language barriers between officers, who were mostly Austrian, and soldiers, who were often Hungarian, Czech, Slovak or from other ethnic groups.

Arnold Schwarzenegger's Austrian Roots and Home

You may want to see also

It was formed by a merger of two older states in 1867

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, also known as the Dual Monarchy, was formed in 1867 through a merger of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary. This merger, known as the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, was a constitutional agreement between Vienna and Budapest, resulting in a multi-national constitutional monarchy. The two kingdoms became semi-independent states with their own parliaments, prime ministers, cabinets and self-governance. However, they were united under a single monarch, Emperor Franz Joseph, who was crowned King of Hungary. The central government, led by the emperor, oversaw foreign policy, military command and joint finance.

The origins of the Dual Monarchy can be traced back to the 1848 revolutions, which saw nationalist and liberal sentiments rise across the Austrian Empire. Hungary, in particular, sought independence, resulting in a brief war in 1848. The Hungarians lost, and the Austrian Empire dissolved the Hungarian parliament, imposing totalitarian rule from Vienna. However, Hungarian nationalist sentiments persisted, and the Austrian Empire continued to face external and internal pressures. In 1866, the Austro-Prussian War led to the Venetian lands being ceded to Italian rule. This, along with ongoing Hungarian aspirations for independence, prompted Emperor Franz Joseph to redefine imperial power.

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 gave Hungary greater autonomy, restoring its parliament and control over most internal affairs. However, the monarchy retained authority over defence, foreign affairs and the military. The compromise also maintained a single, unified empire for purposes of war and foreign affairs. This "common monarchy" consisted of the emperor, his court, the minister for foreign affairs, and the minister of war. While there was no common prime minister, the two kingdoms shared a finance ministry responsible for financing the "common" portfolios of foreign affairs and defence.

The formation of the Dual Monarchy was a significant development, creating one of Europe's major powers. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was geographically the second-largest country in Europe and the third most populous, with a diverse mix of people and cultures. It spanned almost 700,000 square kilometres and contained 52 million people, extending from the Tyrol region in the north to the Ukrainian plains and the Transylvanian mountains in the east.

Austria-Hungary's WWI Weakness: Ethnic Divide and Inefficiency

You may want to see also

It was a multi-national constitutional monarchy

The Austria-Hungary empire, also known as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was a vast and diverse realm that existed from 1867 to 1918. It was a unique political entity, a union of two large realms under the rule of the Habsburg monarch. This empire was a multi-national constitutional monarchy, encompassing a wide range of ethnic and linguistic groups, and as such, it presented a complex political landscape.

The empire was formed through the union of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, with the Habsburg Emperor, Franz Joseph, becoming the monarch of both realms. This union was established through the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, also known as the Ausgleich, which created a unique dual monarchy. Within this structure, Austria and Hungary were separate entities, each with its own parliament, government, and laws, with only the monarch and the foreign and military policies uniting them.

This compromise was a recognition of the distinct identities and aspirations of the Hungarian nobility, who had long resisted rule from Vienna. The Hungarians gained significant autonomy, with their own parliament in Budapest, and the kingdom's territory included modern-day Hungary, Slovakia, Transylvania (now part of Romania), and parts of Croatia and Serbia. The Austrian half of the empire, officially known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council, included a diverse array of territories, such as Bohemia, Galicia, and Lodomeria, each with its own unique history and characteristics.

The multi-national nature of the empire meant that it was home to a wide range of peoples, including Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Romanians, and Italians, to name a few. This diversity presented significant challenges in terms of governance and national unity. The empire's leaders struggled to balance the demands and aspirations of these various groups, and tensions often arose over issues of language, culture, and political representation. The empire's complex structure, with its dual parliaments and varying degrees of autonomy for different regions, was an attempt to manage these tensions and accommodate the diverse interests within the empire.

Booking Flights: Iran to Austria

You may want to see also

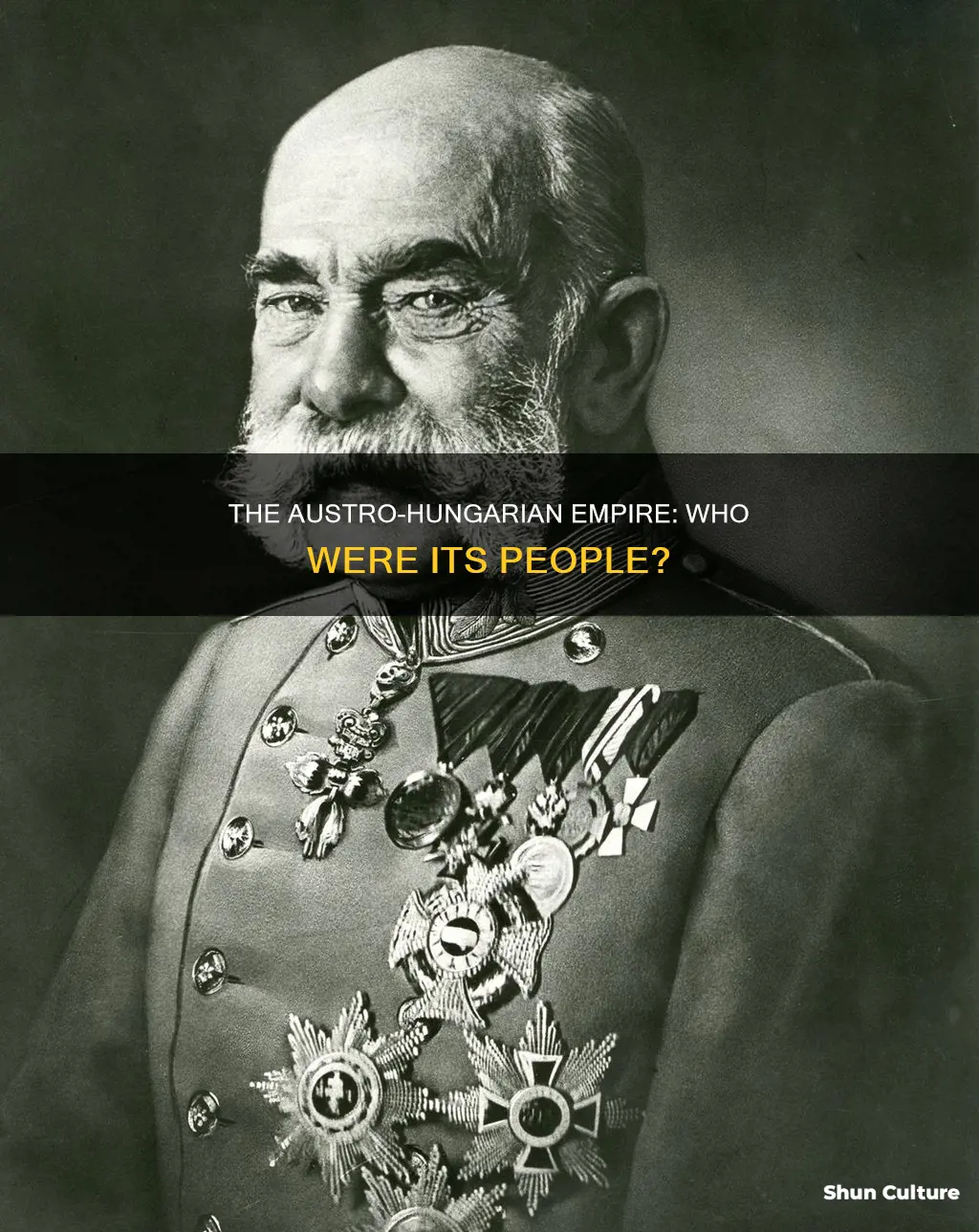

It was ruled by Emperor Franz Joseph

Emperor Franz Joseph I ruled Austria-Hungary from 1848 until his death in 1916. He was 18 when he ascended the throne, following the abdication of his uncle, Emperor Ferdinand I, in the wake of the 1848 Revolution.

Franz Joseph's concept of rulership was informed by a great sense of duty and mission. He endeavoured to re-establish the legitimacy of monarchical rule and to hold together the multinational state that was threatening to break apart. He was forced to make far-reaching concessions, notably in the creation of the dual monarchy through the Compromise with Hungary in 1867 and in consenting to a constitution.

During the first 10 years of his reign, the era of so-called neo-absolutism, the emperor—aided by such outstanding advisers as Felix, prince zu Schwarzenberg—inaugurated a very personal regime by taking a hand both in the formulation of foreign policy and in the strategic decisions of the time. Together with Schwarzenberg, who had become prime minister and foreign minister in 1848, Franz Joseph set out to set his empire in order.

In external affairs, Schwarzenberg achieved a powerful position for Austria; in particular, with the Punctation of Olmütz (November 1850), in which Prussia acknowledged Austria’s predominance in Germany. In home affairs, however, Schwarzenberg’s harsh rule and the formation of an intolerant police apparatus evoked a latent mood of rebellion. This mood became more threatening after 1851, when the government withdrew the promise of a constitution, given in 1849 under the pressure of the revolutionary troubles. That retraction had long after-effects and led to the liberals’ permanent distrust of Franz Joseph’s rule. In 1853 there was an attempt on the emperor’s life in Vienna, and in a riot in Milan.

After Schwarzenberg’s death (1852), Franz Joseph decided not to replace him as prime minister and took a greater part in politics himself. Austria’s mistaken policy during the Crimean War originated largely with the emperor, torn between gratitude to Russia for its help in quelling a rebellion in Hungary in 1849 and the advantage the monarchy might derive from siding with Great Britain and France. The mobilization of a part of the Austrian Army in Galicia on the borders of Russia in retrospect turned out to have been a grave error. It gained no friends for Austria among the Western powers but lost considerable goodwill that Tsar Nicholas I had earlier harboured for Franz Joseph.

At home, neo-absolutism resulted in a civil service staffed by highly competent experts who tried to meet the emperor’s high standards but whose limitations nevertheless became increasingly obvious in 1859–60 as they attempted to deal with the empire’s complex financial problems. Army expenditures had to be curtailed in 1859, when a series of ill-fated wars began that seriously shook Austria’s military reputation. Moreover, the police regime proved to be impracticable in the long run. Thus the government made critical military decisions against a background of many unresolved problems in finances and home affairs. For many of these decisions, especially the unfortunate outcome of the war of 1859 against the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Empire of France, the emperor was responsible. After provoking Austria into war, Camillo Benso, conte di Cavour, the prime minister of Sardinia, planned to use the French Army to oust Austria from Italy. When the imperial commander in chief proved incapable, Franz Joseph himself took over the supreme command, but he could not prevent the defeat of Solferino (June 24, 1859). Dismayed by Prussia’s demand that, as a condition of its intervention on the emperor’s side, the Austrian Army be placed under Prussian command, Franz Joseph hastily concluded the Peace of Villafranca in July 1859, under which Lombardy was ceded to Sardinia. Unreconciled to this settlement, Franz Joseph adopted a foreign policy that prepared the way for a passage at arms with Italy and Prussia, by which he hoped to regain for Austria its former position in Germany and Italy, as it had been established by Metternich in 1814–15.

The mood of crisis after the defeat of 1859 caused Franz Joseph to pay renewed attention to the constitutional question. A period of experiments—alternating between federalistic and centralistic charters—kept the country in a permanent state of crisis until 1867. The congress of princes at Frankfurt in 1863, for which the reigning heads of all German states assembled with the sole exception of the king of Prussia, was a high point in Franz Joseph’s life. Yet the absence of the Prussian king demonstrated that Prussia no longer regarded Austria as the leading German power.

Franz Joseph had vainly tried to postpone the decision for predominance in Germany by entering into a comradeship-in-arms with Prussia in a war against Denmark in 1864. After their victory, squabbles arose between them, and war with Prussia became inevitable. The conclusion of an alliance between Italy and Prussia pointed up the dangerous possibility that both foreign-policy problems might have to be faced at the same time, yet Franz Joseph failed in his attempt to avoid an armed conflict at least with Italy. In June 1866 Austria concluded a possibly unique agreement with Napoleon III of France that stipulated that Austrian-held Venetia was to be given to the Kingdom of Sardinia regardless of the outcome of the impending war with Prussia. As the emperor considered it incompatible with the army’s honour to cede a province without fighting, war with Italy broke out despite the agreement. In later years, Franz Joseph characterized his policy of yielding territory with one hand while fighting for it with the other as honest but stupid, whereas the chancellor Friedrich Ferdinand, Graf (count) von Beust, called the agreement the most shocking document that he had ever seen. Although its defeat in the war with Prussia that the Prussian prime minister Otto von Bismarck had forced on the unprepared monarchy caused Austria no territorial loss in the north, it nevertheless sealed Austria’s expulsion from Germany. The

Zhou's Austrian GP: Will He Race?

You may want to see also

It was geographically the second-largest country in Europe

Austria-Hungary, also known as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was a military and diplomatic alliance consisting of two sovereign states with a single monarch, who was titled both Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary.

Austria-Hungary was geographically the second-largest country in Europe, spanning almost 700,000 square kilometres. It extended from the mountainous Tyrol region north of Italy, to the fertile plains of Ukraine, to the Transylvanian mountains of eastern Europe. The empire was formed in 1867 by a compromise agreement between Vienna and Budapest, resulting in a dual monarchy.

The empire was a relatively young nation-state, containing a rich mix of people and cultures. There were 11 major ethno-language groups scattered across the empire: Germans, Hungarians, Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croatians, Serbs, Italians and Romanians. The empire's political organisation was complex and unusual, reflecting its origins as two separate kingdoms. The emperor was first crowned as king of both Austria and Hungary, with each monarchy continuing to exist with a degree of autonomy.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was one of Europe's major powers. It was the third-most populous country in Europe, after Russia and the German Empire, and was among the ten most populous countries worldwide. It had the fourth-largest machine-building industry in the world and was also a significant agricultural producer, with the east of the empire serving as its agricultural heartland.

The empire's capital, Vienna, was a bustling modern city by the early 20th century, comparable to London and Paris. The empire's rapid industrialisation and modernisation led to improvements in trade, employment and living standards. It had one of Europe's best rail networks by 1900, and its military was powerful and modernised, though undermined by internal political and ethnic divisions.

Austria's FPO: Friend or Foe of the EU?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The people of Austria-Hungary were called Austria-Hungarians or Austro-Hungarians.

The official name of the state was the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy.

The two parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were the Kingdom of Hungary and the Austrian Empire.