The history of Austria and Germany are intertwined, with the two countries sharing a language and a border. The two countries have been in conflict for centuries, with the rivalry between Prussia and Austria being a notable example.

Austria, a landlocked country in Central Europe, is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna. The country is bordered by Germany to the northwest, the Czech Republic to the north, Slovakia to the northeast, Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the west.

Austria, as a unified state, emerged from the remnants of the Eastern and Hungarian March at the end of the first millennium, first as a frontier march of the Holy Roman Empire. It then developed into a Duchy in 1156 and was made an Archduchy in 1453. Being the heartland of the Habsburg monarchy since the late 13th century, Austria was a major imperial power in Central Europe for centuries and from the 16th century, Vienna was also serving as the Holy Roman Empire's administrative capital.

The rivalry between Prussia and Austria began in 1740 when the death of the Habsburg emperor Charles VI without a male heir unleashed the most embittered conflict in Germany since the wars of Louis XIV. The question of the succession to the Austrian throne had occupied statesmen for decades, with rival claimants disputing the right of Charles' daughter Maria Theresa to succeed. France supported them, with its aim being, as before, the fragmentation of the Habsburg state.

However, it was the new Prussian king, Frederick II, who began the conflict. To understand what follows, the modern reader should remember that few observers, even in the enlightened 18th century, disputed a ruler's right to do what he wished with his state. Dynastic aggrandizement, territorial expansion, prestige, honour, power, and princely glory were legitimate grounds for war and sound reasons for demanding the sacrifices necessary to wage it. The only position from which to oppose this arrogation was the Christian ethic, but to do so had proved futile when last tried by Erasmus and Sir Thomas More in the 16th century. No checks—philosophical, moral, or political—therefore restrained kings from indulging their taste for conquests.

Soon after assuming power, Frederick reversed his father's cautious policy of building and hoarding, rather than deploying, Brandenburg-Prussia's military potential. He attacked Silesia, a province in the kingdom of Bohemia and thus part of the Habsburg monarchy, which Prussia had long desired for its populousness, mineral resources, and advanced economy. In exchange for an Austrian cession of Silesia, he offered to accept the Pragmatic Sanction (formally recognised by his predecessor in the 1728 Treaty of Berlin) and support the candidacy of Maria Theresa's husband, Francis Stephen, as emperor. But the resolute woman who now headed the Austrian Habsburgs (1740–80) decided to defend the integrity of her realm, and the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48; including the Silesian Wars between Prussia and Austria) began in 1740. Austria was helped only by a Hungarian army, though initial financial support came from England. Prussia was joined by Bavaria and Saxony in the empire as well as by France and Spain. The Prussian armies, though greatly outnumbered by Austria's forces, revealed themselves as by far the best as well as the best-led. The Treaties of Dresden (1745) and Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) confirmed the Prussian conquest of Silesia. During the succeeding Seven Years' War (1756–63), Prussian forces occupied Saxony, which had allied itself with Austria. In the Treaty of Hubertusburg of 1763, Prussia kept Silesia but could not hold on to Saxony.

What You'll Learn

- The Austrian Empire was a major imperial power in Central Europe for centuries

- Austria was the heartland of the Habsburg monarchy since the late 13th century

- The Austrian-Hungarian rule of this diverse empire included various groups, including Germans, Hungarians, Croats, Czechs, Poles, Rusyns, Serbs, Slovaks, Slovenes, and Ukrainians, as well as large Italian and Romanian communities

- Austria was a founding member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and is a member of the European Union

- The Austrian Armed Forces (Austrian German: Bundesheer) mainly relies on conscription

The Austrian Empire was a major imperial power in Central Europe for centuries

The Austrian Empire was created by Francis II in 1804 in response to Napoleon's declaration of the First French Empire, unifying all Habsburg possessions under one central government. It remained part of the Holy Roman Empire until the latter's dissolution in 1806. It continued fighting against Napoleon throughout the Napoleonic Wars, except for a period between 1809 and 1813, when Austria was first allied with Napoleon during the invasion of Russia and later neutral during the first few weeks of the Sixth Coalition War.

Austrian Air: A Top-Tier Airline Experience?

You may want to see also

Austria was the heartland of the Habsburg monarchy since the late 13th century

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as the Habsburg Empire or Habsburg Realm, was a collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ruled by the House of Habsburg. The history of the Habsburg monarchy can be traced back to the election of Rudolf I as King of Germany in 1273 and his acquisition of the Duchy of Austria for the Habsburgs in 1282. From that moment, the Habsburg dynasty was also known as the House of Austria.

Rudolf I spent several years establishing his authority in Austria, finding some difficulty in establishing his family as successors to the rule of the province. At length, the hostility of the princes was overcome, and he was able to bequeath Austria to his two sons. In December 1282, at the Diet of Augsburg, Rudolf invested the duchies of Austria and Styria on his sons, Albert I and Rudolf II as co-rulers "jointly and severally", and so laid the foundation of the House of Habsburg.

Rudolf continued his campaigns, subduing and subjugating and adding to his domains, dying in 1291, but leaving dynastic instability in Austria, where frequently the Duchy of Austria was shared between family members. However, Rudolf was unsuccessful in ensuring the succession to the imperial throne for the Dukes of Austria and Styria. The conjoint dukedom lasted only a year until the Treaty of Rheinfelden in 1283 established the Habsburg order of succession. Establishing primogeniture, then eleven-year-old Duke Rudolf II had to waive all his rights to the thrones of Austria and Styria to the benefit of his elder brother Albert I. While Rudolf was supposed to be compensated, this did not happen, dying in 1290, and his son John subsequently murdered his uncle Albert I in 1308. For a brief period, Albert I also shared the duchies with Rudolf III the Good (1298-1307), and finally achieved the imperial throne in 1298.

On Albert I's death, the duchy but not the empire passed to his son, Frederick the Fair (1308-1330), at least not until 1314 when he became co-ruler of the empire with Louis IV. Frederick also had to share the duchy with his brother Leopold I the Glorious (1308-1326). Yet another brother, Albert II the Lame (1330-1358) succeeded Frederick. The pattern of corule persisted, since Albert had to share the role with another younger brother Otto I the Merry (1330-1339), although he did attempt to unsuccessfully lay down the rules of succession in the "Albertinian House Rule". When Otto died in 1339, his two sons, Frederick II and Leopold II replaced him, making three simultaneous Dukes of Austria from 1339 to 1344 when both of them died in their teens without issue. Single rule in the Duchy of Austria finally returned when his son, Rudolf IV succeeded him in 1358.

The Nazis in Austria: A Chilling Reception

You may want to see also

The Austrian-Hungarian rule of this diverse empire included various groups, including Germans, Hungarians, Croats, Czechs, Poles, Rusyns, Serbs, Slovaks, Slovenes, and Ukrainians, as well as large Italian and Romanian communities

The Austrian-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 ended the 18-year-long military dictatorship and absolutist rule over Hungary which Emperor Franz Joseph had instituted after the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. The Compromise put an end to the 1848 Revolution, in which the Kingdom of Hungary called for greater self-government and later even independence from the Austrian Empire. The Hungarian parliament was re-established, as it had been the supreme legislative power in Hungary since the 12th century. The Austrian-Hungarian Empire was geographically the second-largest country in Europe and the third-most populous (after Russia and the German Empire), while being among the ten most populous countries worldwide.

The two halves of the monarchy were referred to as Cisleithania, the northern and western parts of the former Austrian Empire, and Transleithania (Kingdom of Hungary). The Austrian and Hungarian states were governed by separate parliaments and prime ministers. The two countries conducted unified diplomatic and defence policies. For these purposes, "common" ministries of foreign affairs and defence were maintained under the monarch's direct authority, as was a third finance ministry responsible only for financing the two "common" portfolios. The Austrian-Hungarian Empire was one of the Central Powers in World War I, which began with an Austro-Hungarian war declaration on the Kingdom of Serbia on 28 July 1914. It was already effectively dissolved by the time the military authorities signed the armistice of Villa Giusti on 3 November 1918.

Watch Austria vs France: Live Stream Guide

You may want to see also

Austria was a founding member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and is a member of the European Union

Austria was a founding member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which was established in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade. The OECD is an intergovernmental organisation with 38 member countries. Austria is also a member of the European Union, which it joined in 1995.

The OECD was founded as a successor to the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC), which was established in 1948 to coordinate efforts in restoring Europe's economy under the Marshall Plan. The OEEC's primary function was the allocation of American aid.

Austria's involvement in the OECD is in line with its commitment to democracy and the market economy, providing a platform for the country to compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, and coordinate domestic and international policies with other member countries.

Austria's membership in the OECD and the European Union reflects its proactive role in the global economy and its dedication to international cooperation and collaboration.

Austria's Annexation: Joining the Reich

You may want to see also

The Austrian Armed Forces (Austrian German: Bundesheer) mainly relies on conscription

The Austrian Armed Forces, also known as the Bundesheer, are the combined military forces of Austria. The Austrian military mainly relies on conscription, with the armed forces consisting of 16,000 active-duty personnel and 125,600 reservists. In times of peace, the Austrian Armed Forces comprise professional soldiers, further employees, and conscripts. The task force organisation also includes militia soldiers.

The Austrian Armed Forces are divided into the air force, land-based forces, special forces, and cyber forces. The air force, or Luftstreitkräfte, has as its missions the defence of Austrian airspace, tactical support of Austrian ground forces, reconnaissance, military transport, and search-and-rescue support when requested by civil authorities.

The Austrian Armed Forces' main purpose since 1955 has been the protection of Austria's neutrality. Its relationship with NATO is limited to the Partnership for Peace programme. The Austrian military has increasingly assisted the border police in controlling the influx of undocumented migrants through Austrian borders.

The Austrian Armed Forces consist solely of the army, of which the air force is considered a constituent part. In 1993, the total active complement of the armed forces was 52,000, of whom 20,000 to 30,000 were conscripts undergoing training of six to eight months. The army had 46,000 personnel on active duty (including an estimated 19,500 conscripts), and the air force had 6,000 personnel (2,400 conscripts).

Hitler's Nationality: Austrian Roots, German Leadership

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Austria is older than Germany. The area that is now Austria has been inhabited since at least the Paleolithic period. Around 400 BC, it was inhabited by the Celts and then annexed by the Romans in the late 1st century BC. Austria, as a unified state, emerged from the remnants of the Eastern and Hungarian March at the end of the first millennium, first as a frontier march of the Holy Roman Empire. It then developed into a Duchy in 1156, and was made an Archduchy in 1453. Being the heartland of the Habsburg monarchy since the late 13th century, Austria was a major imperial power in Central Europe for centuries and from the 16th century, Vienna was also serving as the Holy Roman Empire's administrative capital.

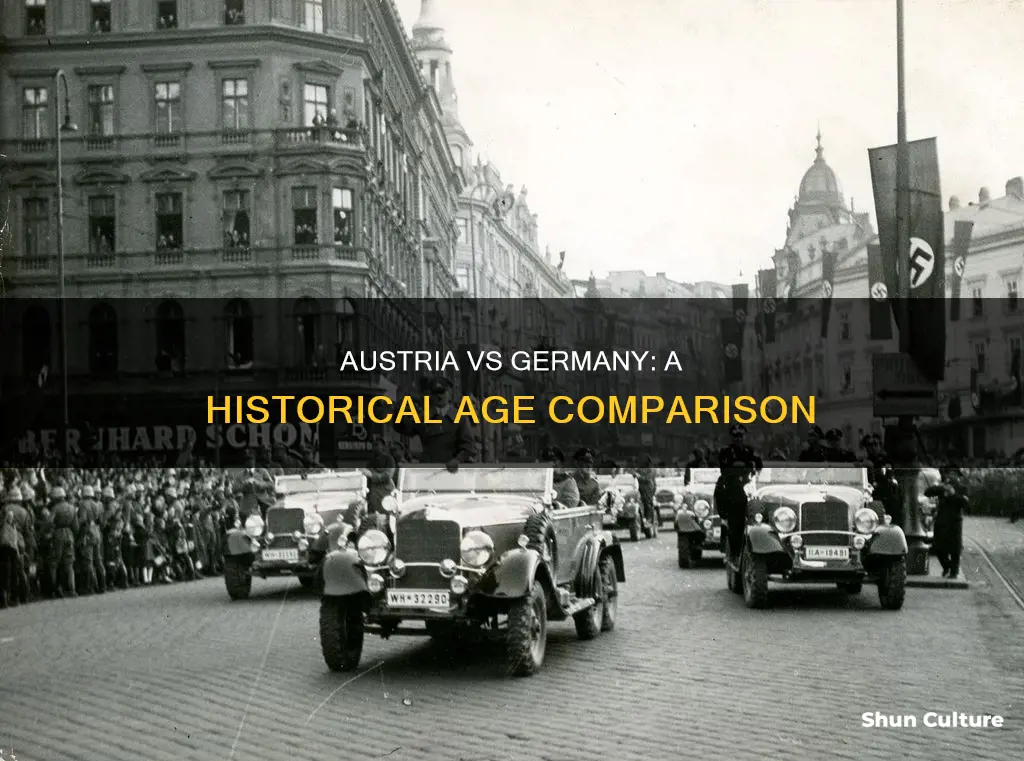

The Treaty of Saint Germain of 1919 (for Hungary the Treaty of Trianon of 1920) confirmed and consolidated the new order of Central Europe which to a great extent had been established in November 1918, creating new states and altering others. The German-speaking parts of Austria which had been part of Austria-Hungary were reduced to a rump state named the Republic of German-Austria (German: Republik Deutschösterreich), though excluding the predominantly German-speaking South Tyrol. The desire for the annexation of Austria to Germany was a popular opinion shared by all social circles in both Austria and Germany. On 12 November, German-Austria was declared a republic, and named Social Democrat Karl Renner as provisional chancellor. On the same day, it drafted a provisional constitution that stated that "German-Austria is a democratic republic" (Article 1) and "German-Austria is an integral part of the German reich" (Article 2). The Treaty of Saint Germain and the Treaty of Versailles explicitly forbade union between Austria and Germany. The treaties also forced German-Austria to rename itself as "Republic of Austria" which consequently led to the first Austrian Republic.

The Austria–Prussia rivalry began in Germany. The rise of Prussia and the Austria–Prussia rivalry began in Germany. Austria participated, together with Prussia and Russia, in the first and the third of the three Partitions of Poland in 1772 and 1795 respectively. The two countries also fought each other in the Austro-Prussian War in 1866.