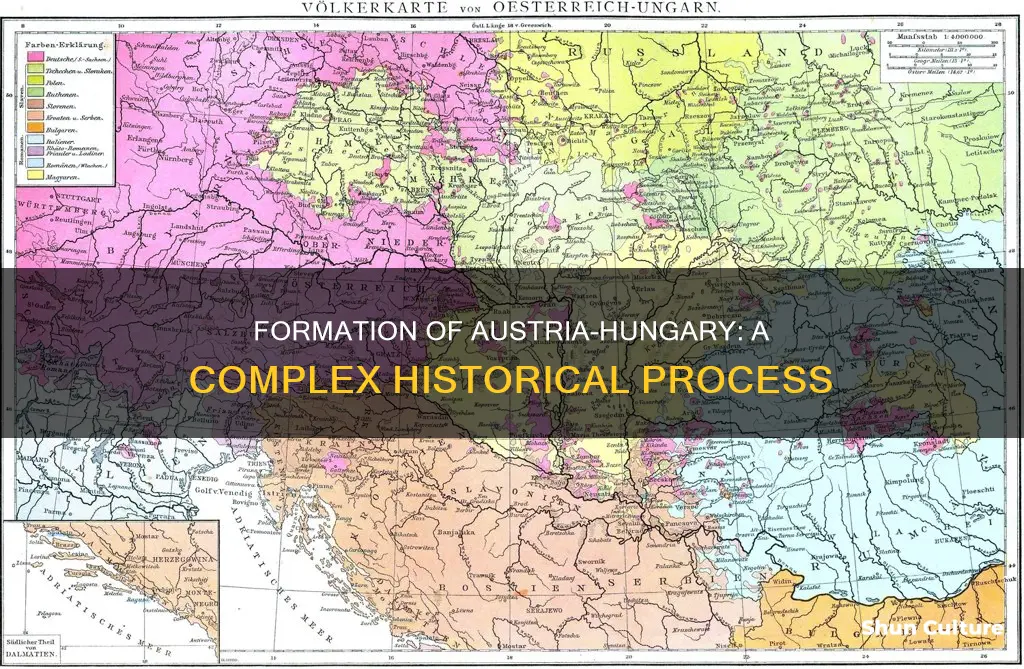

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, also known as the Dual Monarchy, was formed in 1867 following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise. This compromise joined the Kingdom of Hungary and the Empire of Austria as two separate entities with equal status, each retaining its own parliament, prime minister, and domestic self-government. The agreement created a king of Hungary in addition to the existing Austrian emperor, with Francis Joseph holding both titles from the inception of the Dual Monarchy until his death in 1916.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Years of existence | 1867-1918 |

| Type of state | Dual monarchy |

| Formation | Compromise agreement between Vienna and Budapest |

| Number of states | Two: Kingdom of Hungary and Empire of Austria |

| Monarch | Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary |

| Government type | Autocratic, dominated by aristocrats and militarists |

| Parliaments | Two: one for each monarchy |

| Prime ministers | Two: one for each monarchy |

| Cabinets | Two: one for each monarchy |

| Population | 52 million |

| Area | 700,000 sq km |

| Number of ethno-language groups | 11 |

| Number of successor states | Two: German Austria and Hungarian Democratic Republic |

What You'll Learn

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867

The Compromise of 1867 formed a real union between the Austrian Empire ("Lands Represented in the Imperial Council", or Cisleithania) in the western and northern half, and the Kingdom of Hungary ("Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen", or Transleithania) in the eastern half. This established a military and diplomatic alliance of two sovereign states with a single monarch, who was titled both Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary. While the two halves shared a common monarch, they maintained separate identities, with distinct parliaments, prime ministers, and governments.

Under the Compromise, Hungary regained significant internal autonomy, and its historic constitution and territorial integrity were restored. The Hungarian parliament, which had been the supreme legislative power in Hungary since the 12th century, was re-established, and the April Laws of the Hungarian revolutionary parliament were accepted by Emperor Franz Joseph. Additionally, the Hungarian legal and judicial systems were restored, and Hungarian became the official language of public administration.

In return, Hungary agreed that the empire should remain a single great state for purposes of war and foreign affairs, with unified diplomatic and defence policies. Common ministries for foreign affairs, defence, and finance (for expenditures related to the common portfolios) were established under the monarch's direct authority. A third component of the union was the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, an autonomous region under the Hungarian crown, which negotiated the Croatian-Hungarian Settlement in 1868.

The Compromise of 1867 was a result of negotiations between the central government in Vienna, led by Emperor Franz Joseph, and Hungarian political leaders, led by Ferenc Deák. It came into force when passed as a constitutional law by the Hungarian parliament in March 1867. This agreement transformed the relationship between Austria and Hungary, shaping the political landscape of the region until the dissolution of the Dual Monarchy in 1918.

Austria's Annexation: Did They Want German Unification?

You may want to see also

The Dual Monarchy

The Compromise of 1867 granted Hungary full internal autonomy, with its own parliament, prime minister, cabinet, and domestic self-government. In return, Hungary agreed that the empire should remain a single great state for purposes of war and foreign affairs, with a common ministry for foreign affairs and defence under the monarch's direct authority. Additionally, a third finance ministry was responsible for financing these two "common" portfolios.

SKF Bearings: Austrian-Made or Not?

You may want to see also

The Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg, a royal German family, was one of the principal sovereign dynasties of Europe from the 15th to the 20th century. The name 'Habsburg' is derived from the castle of Habsburg, or Habichtsburg ("Hawk's Castle"), built in 1020 by Werner, bishop of Strasbourg, and his brother-in-law, Count.

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a multinational European great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. It was the third most populous monarchy in Europe after the Russian Empire and the United Kingdom, and geographically, it was the third-largest empire in Europe after the Russian Empire and the First French Empire.

The empire was proclaimed by Francis II in 1804 in response to Napoleon's declaration of the First French Empire, unifying all Habsburg possessions under one central government. It remained part of the Holy Roman Empire until the latter's dissolution in 1806.

The Kingdom of Hungary—as Regnum Independens—was administered by its own institutions separately from the rest of the empire. After Austria was defeated in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 was adopted, joining the Kingdom of Hungary and the Empire of Austria to form Austria-Hungary. This was also known as the Dual Monarchy, as the emperor was first crowned as king of both Austria and Hungary. Each monarchy continued to exist with a degree of autonomy, with its own parliament, prime ministers, cabinet, and domestic self-government.

The Compromise of 1867 turned the Habsburg domains into a real union between the Austrian Empire ("Lands Represented in the Imperial Council", or Cisleithania) in the western and northern half, and the Kingdom of Hungary ("Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen", or Transleithania) in the eastern half. The government of Austria, which had ruled the monarchy until 1867, became the government of the Austrian part, and another government was formed for the Hungarian part. A common government was formed for a few matters of common national security: the Common Army, Navy, foreign policy, and the imperial household, and the customs union. Although the two halves shared a common monarch, and both foreign relations and defence were managed jointly, all other state functions were handled separately, as there was no common citizenship.

Hungary and Austria maintained separate parliaments, each with its own prime minister: the Diet of Hungary (commonly known as the National Assembly) and the Imperial Council (Reichsrat) in Cisleithania. Each parliament had its own executive government, appointed by the monarch.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was a military and diplomatic alliance, consisting of two sovereign states with a single monarch who was titled both Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary. It was the last phase in the constitutional evolution of the Habsburg monarchy.

Napoleon's Peace: Britain and Austria's Treaty

You may want to see also

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848

In April 1848, Hungary became the third country in continental Europe to enact a law implementing democratic parliamentary elections. The new suffrage law (Act V of 1848) transformed the old feudal parliament (Estates General) into a democratic representative parliament. This law offered the widest right to vote in Europe at the time. The April laws utterly erased all privileges of the Hungarian nobility.

The crucial turning point came when the new Austrian monarch Franz Joseph I arbitrarily revoked the April laws without any legal right. This unconstitutional act irreversibly escalated the conflict between him and the Hungarian parliament. The new constrained Stadion Constitution of Austria, the revocation of the April laws, and the Austrian military campaign against the Kingdom of Hungary resulted in the fall of the pacifist Batthyány government and led to Lajos Kossuth's followers suddenly gaining power in the parliament. Austrian military intervention in the Kingdom of Hungary resulted in strong anti-Habsburg sentiment among Hungarians, and the events in Hungary grew into a war for total independence from the Habsburg dynasty.

The Hungarian government was in a serious military crisis due to the lack of soldiers, so they sent Kossuth (a brilliant orator) to recruit volunteers for the new Hungarian army. Kossuth quickly formed the Hungarian Revolutionary Army. 40% of private soldiers in the revolutionary army consisted of ethnic minorities of the country. The new Hungarian army defeated the Croatians on 29 September at the Battle of Pákozd.

The battle became an icon for the Hungarian army for its effect on politics and morale. Kossuth's second letter to the Austrian people and this battle caused the second revolution in Vienna on 6 October.

In April 1849, Tsar Nicholas I pledged to redouble his efforts against the Hungarian Government. He and Emperor Franz Joseph started to regather and rearm an army to be commanded by Anton Vogl, the Austrian lieutenant-field-marshal. But even at this stage, Vogl was occupied trying to stop another revolutionary uprising in Galicia. The Tsar was also preparing to send 30,000 Russian soldiers back over the Eastern Carpathian Mountains from Poland. Austria held Galicia and moved into Hungary, independent of Vogl's forces. At the same time, the able Julius Jacob von Haynau led an army of 60,000 Austrians from the West and retook the ground lost throughout the spring. On 18 July, he finally captured Buda and Pest. The Russians were also successful in the east, and the situation of the Hungarians became increasingly desperate.

On 13 August, after several bitter defeats, especially the battle of Segesvár against the Russians and the battles of Szöreg and Temesvár against the Austrian army, it was clear that Hungary had lost. In a hopeless situation, Görgey signed a surrender at Világos (now Şiria, Romania) to the Russians, who handed the army over to the Austrians.

The Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–49 caused fundamental, decisive changes in social thinking, and in a short time transformed bold ideas into laws, which could not be negated even when they had been abolished by the "old order". But only for a short while, because the ideas of the Reform Age and Revolution became again laws, winning the final victory after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867.

Exploring Am See, Austria: A Lakeside Paradise

You may want to see also

The Austro-Prussian War

The Road to War

The major result of the war was a shift in power among the German states away from Austrian and towards Prussian hegemony. It resulted in the abolition of the German Confederation and its partial replacement by the unification of all of the northern German states in the North German Confederation, which excluded Austria and the other southern German states. The war also resulted in the Italian annexation of the Austrian realm of Venetia.

The war erupted as a result of the dispute between Prussia and Austria over the administration of Schleswig-Holstein, which the two of them had conquered from Denmark and agreed to jointly occupy at the end of the Second Schleswig War in 1864. The crisis started on 26 January 1866, when Prussia protested the decision of the Austrian Governor of Holstein to permit the estates of the duchies to call up a united assembly, declaring the Austrian decision a breach of the principle of joint sovereignty. Austria replied on 7 February, asserting that its decision did not infringe on Prussia's rights in the duchies. In March 1866, Austria reinforced its troops along its frontier with Prussia. Prussia responded with a partial mobilization of five divisions on 28 March.

The Prussian Minister President Otto von Bismarck made an alliance with Italy on 8 April, committing it to the war if Prussia entered one against Austria within three months, which was an obvious incentive for Bismarck to go to war with Austria within three months so that Italy would divert Austrian strength away from Prussia. Austria responded with a mobilization of its Southern Army on the Italian border on 21 April. Italy called for a general mobilization on 26 April, and Austria ordered its own general mobilization the next day. Prussia's general mobilization orders were signed in steps on 3, 5, 7, 8, 10 and 12 May.

When Austria brought the Schleswig-Holstein dispute before the German Diet on 1 June and also decided on 5 June to convene the Diet of Holstein on 11 June, Prussia declared that the Gastein Convention of 14 August 1865 had thereby been nullified and invaded Holstein on 9 June. When the German Diet responded by voting for a partial mobilization against Prussia on 14 June, Bismarck claimed that the German Confederation had ended. The Prussian Army invaded Hanover, Saxony and the Electorate of Hesse on 15 June. Italy declared war on Austria on 20 June.

The War

The first major war between two continental powers in many years, this war used many of the same technologies as the American Civil War, including the use of railroads to concentrate troops during mobilization and the use of telegraphs to enhance long-distance communication. The Prussian Army used breech-loading rifles that could be loaded while the soldier was seeking cover on the ground, whereas the Austrian muzzle-loading rifles could be loaded only while standing (thus offering no cover).

The main campaign of the war occurred in Bohemia. Prussian Chief of the General Staff Helmuth von Moltke had planned meticulously for the war, and chose to mostly ignore the minor states in favor of a concentration against Austria. He rapidly mobilized the Prussian army and advanced across the border into Saxony and Bohemia, where the Austrian army was concentrating for an invasion of Silesia. There, the Prussian armies led personally by Wilhelm I converged, and the two sides met at the Battle of Königgrätz (Sadová) on July 3. Superior Prussian organization and élan decided the battle against Austrian numerical superiority, and the victory was near total, with Austrian battle deaths nearly seven times the Prussian figure. It is worth noting that Prussia was equipped with Johann Nicholas von Dreyse's breech-loading needle-gun, which was vastly superior to Austria's muzzle-loaders. Austria rapidly sought peace after this battle.

Except for Saxony, the other German states allied to Austria played little role in the main campaign. Hanover's army defeated Prussia at Langensalza on June 27, but within a few days, they were forced to surrender by superior numbers. Prussian armies fought against Bavaria on the Main River, reaching Nuremberg and Frankfurt. The Bavarian fortress of Würzburg was shelled by Prussian artillery, but the garrison defended its position until armistice day.

The Austrians were more successful in their war with Italy, defeating the Italians on land at the Battle of Custoza (June 24) and on sea, at the Battle of Lissa (July 20). Garibaldi's "Hunters of the Alps" defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Bezzecca, on July 21, conquered the lower part of Trentino, and moved towards Trento. Prussian peace with Austria-Hungary forced the Italian government to seek an armistice with Austria, on August 12. According to the Treaty of Vienna (1866), signed on October 12, Austria ceded Venetia to France, which in turn ceded it to Italy.

Aftermath

In order to forestall intervention by France or Russia, Otto von Bismarck pushed the king to make peace with the Austrians rapidly, rather than continue the war in hopes of further gains. The Austrians accepted mediation from France's Napoleon III. The Treaty of Prague on August 23, 1866, resulted in the dissolution of the German Confederation, Prussian annexation of Schleswig-Holstein, Hanover, Hesse-Kassel, Nassau, and Frankfurt, and the permanent exclusion of Austria from German affairs. This left Prussia free to form the North German Confederation the next year. Prussia chose not to seek Austrian territory for itself, and this made it possible for Prussia and Austria to ally in the future, since Austria was threatened more by Italian and Pan-Slavic irredentism than by Prussia.

The war left Prussia dominant in Germany, and German nationalism would compel the remaining independent states to ally with Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, and then to accede to the crowning of King Wilhelm as German Emperor. United Germany would become one of the

Austria's Power Play: Hard or Soft?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Austria-Hungary was formed in 1867 by the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, also known as the Compromise of 1867.

The Compromise of 1867 was an agreement between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, which allowed them to join on an equal basis to form a dual monarchy.

The Austro-Prussian War of 1866 led to the expulsion of Austria from the German Confederation and caused Emperor Franz Joseph to reorient his policy towards the east. This defeat also provided the Hungarians with an opportunity to remove the shackles of absolutist rule, which had been imposed on them after the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 was crushed by the Austrian military with Russian support.

The dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary was a multi-national constitutional monarchy with two sovereign states, a single monarch, and two separate governments. The emperor was crowned as both the Emperor of Austria and the King of Hungary, with each monarchy retaining autonomy, its own parliament, prime minister, cabinet, and domestic self-government.