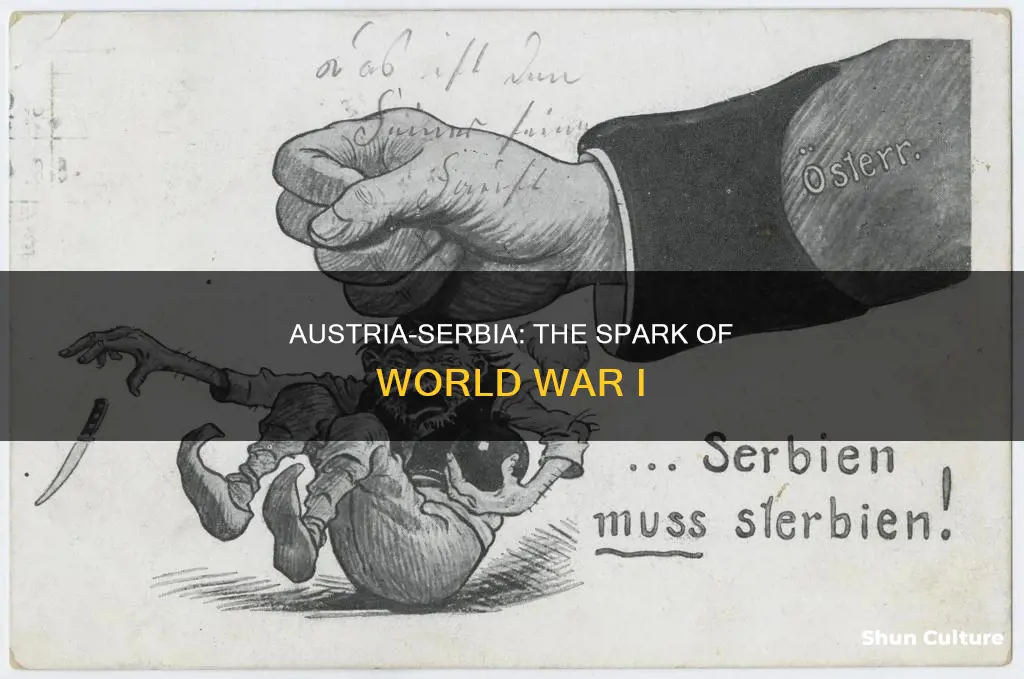

The Kingdom of Serbia and Austria-Hungary were neighbouring states with a history of conflict and rising tensions in the lead-up to World War I. Serbia, sandwiched between Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, occupied a strategically important position. Its independence from the Ottomans in the 1800s brought it under the political and economic control of Austria-Hungary, which sought to suppress Serbian nationalism and pan-Slavism. The annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina by Austria-Hungary in 1908, and subsequent crises, fuelled Serbian anger and further escalated tensions. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Bosnian Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip in 1914 became a flashpoint, triggering a diplomatic crisis and ultimately leading to Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia. This dispute escalated into World War I, drawing in other major European powers.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia | 28 July 1914 |

| Reason for declaration of war | Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Gavrilo Princip |

| Austria-Hungary's allies | Germany, Bulgaria, Ottoman Empire |

| Serbia's allies | Russia, France, Montenegro |

| Outcome of first invasion attempt | Failure |

| Number of invasion attempts | 3 |

| Result of war | Austria-Hungary occupies Serbia in 1915 |

What You'll Learn

The Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Princip was part of a group of six Bosnian assassins, five of whom were Bosnian Serbs and members of a student revolutionary group that later became known as Young Bosnia. The political objective of the assassination was to free Bosnia and Herzegovina of Austria-Hungarian rule and establish a common South Slav ("Yugoslav") state. The assassination precipitated the July Crisis, which led to Austria-Hungary declaring war on Serbia and the start of World War I.

The day of the assassination, 28 June, is the feast of St. Vitus. In Serbia, it is called Vidovdan and commemorates the 1389 Battle of Kosovo against the Ottomans. Princip and his fellow assassins were inspired by the heroism of Miloš Obilić, reenacting the Kosovo Myth.

On the morning of 28 June 1914, the assassins fanned out along the motorcade route in Sarajevo. Franz Ferdinand and his party arrived at Sarajevo station, where six automobiles were waiting. The third car in the motorcade was an open-topped sports car in which Franz Ferdinand, Sophie, Governor Potiorek, and Lieutenant Colonel Count Franz von Harrach rode.

As the motorcade passed by, Nedeljko Čabrinović threw a bomb at the car, which bounced off and rolled underneath the wrong vehicle. The bomb exploded under the next car, wounding two army officers and several bystanders but leaving Franz Ferdinand and Sophie essentially unharmed. Čabrinović swallowed a cyanide pill and jumped into the river but was dragged out by police and severely beaten by the crowd before being taken into custody.

The procession sped away towards the Town Hall, leaving the disabled car behind. Arriving at the Town Hall, Franz Ferdinand showed signs of stress, interrupting a prepared speech of welcome to protest the bombing. Duchess Sophie whispered into Franz Ferdinand's ear, and he became calm and allowed the mayor to give his speech.

After the reception, Franz Ferdinand and Sophie gave up their planned program in favour of visiting the wounded from the bombing at the hospital. In order to avoid the crowded city centre, it was decided that the imperial motorcade should travel straight along the Appel Quay to the Sarajevo Hospital. However, the drivers were not informed of the change in plans, and the Archduke's driver turned onto a side street, where Princip happened to be standing. Princip stepped up to the car and shot Franz Ferdinand and Sophie at point-blank range. Within minutes, both had passed away.

With tensions already running high among Europe's powers, the assassination precipitated a rapid descent into World War I. Austria-Hungary gained German support for punitive action against Serbia and sent an ultimatum, worded in a way that made acceptance unlikely. Serbia proposed arbitration to resolve the dispute, but Austria-Hungary instead declared war on 28 July 1914, exactly a month after Franz Ferdinand's death. By the following week, Germany, Russia, France, Belgium, Montenegro, and Great Britain had all been drawn into the conflict, and other countries like the United States would enter later. Overall, more than 16 million people—soldiers and civilians—died in fighting that lasted until 1918.

Austrian Pine Elevation: Growth Secrets Revealed

You may want to see also

The July Crisis

Reactions to the Assassination

The news from the Bosnian capital about the assassination of the Austrian heir to the throne hit “like lightning strike”. The previous day, the nineteen-year-old Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip, part of a small group of conspirators who had planned an attack on this representative of the Dual Monarchy, had shot and killed Franz Ferdinand and his wife. The murder of the Archduke caused widespread outrage.

Planning the Ultimatum

In Berlin, the possibility of a Balkan crisis was greeted favourably by military and political decision-makers, for it was felt that such a crisis would ensure that Austria would definitely be involved in a resulting conflict. When Hoyos arrived in Berlin to ascertain the powerful ally’s position in case Austria made demands of Serbia, he was assured that Germany would support Austria unconditionally, even if it chose to go to war over the assassination, and even if such a war were to turn into a European war. This was Germany’s so-called “blank cheque” to Vienna.

The Ultimatum and Mediation Attempts

Hopes that an amicable solution might be found were dashed at 6 p.m. on 23 July, when the Austrian Minister in Belgrade, Wladimir Giesl, delivered a forty-eight-hour ultimatum to the Serbian Foreign Ministry, timed carefully to ensure maximum inconvenience for France and Russia in particular, as the French President was known to be on the way home from St. Petersburg at the time the Austrian demands were handed over. In addition to declaring that the Serbian government was guilty of tolerating the existence of a subversive movement in Serbia, which opposed the annexation of Bosnia by Austria-Hungary, the text of the ultimatum demanded that Belgrade would have to accept the annexation of Bosnia. It was asked to issue an official apology in the Serbian press, distancing itself from “the whole body of the efforts whose ultimate object it is to separate from the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy territories that belong to it”. Some further ten separate demands forced the Serbian government, inter alia, to suppress all publications which might incite hatred and contempt of the Monarchy; to dissolve the organisation Narodna Odbrana; to eliminate anti-Habsburg teaching materials; to dismiss all officers and officials who have carried out propaganda against Austria-Hungary; to assist Austrian organs to suppress subversive movements in Serbia; to conduct a judicial enquiry against all participants in the 28 June plot; to arrest Major Voija Tankosić and Milan Ciganović, a Serbian government official, “who have both been compromised by the results of the enquiry”; to dismiss and punish those border guards who assisted in the smuggling of weapons into Bosnia.

The Outbreak of War

On 28 July 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. This set in motion a domino effect of mobilisation orders and declarations of war by Europe’s major powers which resulted in a war that far exceeded what they had planned or wanted.

Norwegian Air's Austrian Destinations: Where Can You Fly?

You may want to see also

The July Ultimatum

On the 23rd of July 1914, Austria-Hungary issued an ultimatum to Serbia, nearly a month after the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife by a young Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo, Bosnia. The ultimatum, delivered by the ambassador of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to Serbia, Baron Giesl von Gieslingen, demanded that Serbia:

- Formally distance itself from the political campaign to unite the southern Slav peoples under Serbian leadership, which challenged the territorial integrity of Austria-Hungary.

- Purge the Serbian army and civil service of anti-Austrian agitators and suppress anti-Austrian propaganda in the Serbian press.

- Take legal action against extremist secret organisations operating against Austria, including the Black Hand, which was believed to have aided the assassins by providing weapons and safe passage.

- Allow Austrian officials to participate in the investigation of the assassination on Serbian territory, despite this being a violation of Serbia's state sovereignty.

The ultimatum was intentionally designed to be unacceptable to Serbia, with the sixth point, in particular, making Austrian-Serbian conflict almost inevitable. Serbia was given just 48 hours to respond, and although it accepted all but one of the demands, Austria-Hungary was not interested in a diplomatic solution and broke off diplomatic relations on the 25th of July. On the 28th of July, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, marking the start of World War I.

Skiing in Austria: November Options

You may want to see also

The Balkan Wars

The First Balkan War

The First Balkan War was the result of discontent in Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece caused by disorder in Macedonia. The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 brought into power in Constantinople (now Istanbul) a ministry determined on reform but insisting on the principle of centralized control. There were no concessions to the Christian nationalities of Macedonia, which included Serbs, Bulgarians, Greeks, and Vlachs. The Albanians, whose growing sense of nationalism had been awakened by the Albanian League, were also discontented with the Young Turks' centralist policy.

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), founded in 1893, organized bands to resist the Turkish administration. This roused public opinion in Bulgaria in favour of intervention. A similar development occurred in Serbia, where the patriotic society Narodna Odbrana ("National Defence"), invigorated by the infiltration of the "Union or Death" group (founded in May 1911 and better known as the Black Hand), was active in organizing Serbian resistance in Macedonia. The activity of the Bulgarians in Macedonia had led in September 1903 to the formation of an armed band in defence of Greek interests.

In October 1908, Austria-Hungary seized the opportunity of the Ottoman political upheaval to annex the de jure Ottoman province of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which it had occupied since 1878. Bulgaria declared independence as it had done in 1878, but this time it was internationally recognized. The Greeks of the autonomous Cretan State proclaimed unification with Greece, though opposition from the Great Powers prevented this from taking practical effect.

Serbia was frustrated in the north by Austria-Hungary's incorporation of Bosnia. In March 1909, Serbia was forced to accept the annexation and restrain anti-Habsburg agitation by Serbian nationalists. Instead, the Serbian government looked to formerly Serb territories in the south, notably "Old Serbia" (the Sanjak of Novi Pazar and the province of Kosovo).

On 15 August 1909, the Military League, a group of Greek officers, launched a coup. The Military League sought the creation of a new political system and thus summoned the Cretan politician Eleftherios Venizelos to Athens as its political advisor. Venizelos persuaded King George I to revise the constitution and asked the League to disband in favour of a National Assembly. In March 1910, the Military League dissolved itself.

Bulgaria, which had secured Ottoman recognition of her independence in April 1909 and enjoyed the friendship of Russia, also looked to annex districts of Ottoman Thrace and Macedonia. In August 1910, Montenegro followed Bulgaria's precedent by becoming a kingdom.

The Italo-Ottoman War of 1911 and the Albanian Revolts in the Albanian Provinces showed that the Empire was deeply "wounded" and unable to strike back against another war. The Great Powers quarrelled among themselves and failed to ensure that the Ottomans would carry out the needed reforms. This led the Balkan states to impose their own solution.

The First Balkan War began on 8 October 1912, when the League member states attacked the Ottoman Empire, and ended eight months later with the signing of the Treaty of London on 30 May 1913. The Balkan allies were soon victorious. In Thrace, the Bulgarians defeated the main Ottoman forces, advancing to the outskirts of Constantinople and laying siege to Adrianople (Edirne). In Macedonia, the Serbian army achieved a great victory at Kumanovo that enabled it to capture Bitola and to join forces with the Montenegrins and enter Skopje. The Greeks, meanwhile, occupied Salonika (Thessaloníki) and advanced on Ioánnina. In Albania, the Montenegrins besieged and captured Shkodër, and the Serbs entered Durrës.

The Turkish collapse was so complete that all parties were willing to conclude an armistice on 3 December 1912. A peace conference was begun in London, but after a coup d'état by the Young Turks in Constantinople in January 1913, war with the Ottomans was resumed. Again the allies were victorious: Ioánnina fell to the Greeks and Adrianople to the Bulgarians. Under a peace treaty signed in London on 30 May 1913, the Ottoman Empire lost almost all of its remaining European territory, including all of Macedonia and Albania. Albanian independence was insisted upon by the European powers, and Macedonia was to be divided among the Balkan allies.

The Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War began when Serbia, Greece, and Romania quarreled with Bulgaria over the division of their joint conquests in Macedonia. On 1 June 1913, Serbia and Greece formed an alliance against Bulgaria, and the war began on the night of 29–30 June 1913, when King Ferdinand of Bulgaria ordered his troops to attack Serbian and Greek forces in Macedonia. The Bulgarian offensive, benefiting from surprise, was initially successful, but Greek and Serbian defenders retired in good order.

The Serbian army counterattacked on 2 July and drove a wedge into the Bulgarian line. Greek reserves advanced to the front on 3 July, and a series of attacks over the following days threatened to turn the left flank of an entire Bulgarian army. In an effort to save their force from being cut off entirely, the Bulgarians launched a desperate attack on the Serbian lines. Once again, the Bulgarians achieved momentary success, but by 10 July the offensive had completely stalled. On 11 July the Romanian army crossed the Bulgarian frontier and began an unopposed march on Sofia, the Bulgarian capital. The following day, the

Transfer Money from Austria to Burkina Faso: A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

The Central Powers

- Germany: Germany was the leading power among the Central Powers and played a crucial role in escalating the conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. They provided unconditional support to Austria-Hungary after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, encouraging them to take a firm stance against Serbia. Germany's alliance with Austria-Hungary was a significant factor in the outbreak of World War I.

- Austria-Hungary: Austria-Hungary's conflict with Serbia was a key trigger for World War I. On July 28, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Gavrilo Princip, a Serbian nationalist. This declaration of war set off a chain reaction, leading to a wider European conflict. Austria-Hungary's invasion of Serbia in 1914 marked the beginning of the war, and they fought on multiple fronts, including Serbia, the Eastern Front, Italy, and Romania.

- Bulgaria: Bulgaria joined the Central Powers and fought alongside Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. They played a significant role in the Serbian Campaign, invading Serbia from the north in coordination with Austro-Hungarian and German forces. Bulgaria's involvement was crucial in the defeat and occupation of Serbia, which gave the Central Powers temporary control over the Balkans.

- The Ottoman Empire: The Ottoman Empire, also known as the Turkish Empire, was part of the Central Powers and provided an important strategic link between Europe and the Middle East. The German Chief of Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, recognised the importance of conquering Serbia to establish a direct rail link from Germany to Istanbul, allowing them to resupply the Ottoman Empire throughout the war.

Austrian Airlines' Do&Co: Elevating In-Flight Dining Experience

You may want to see also