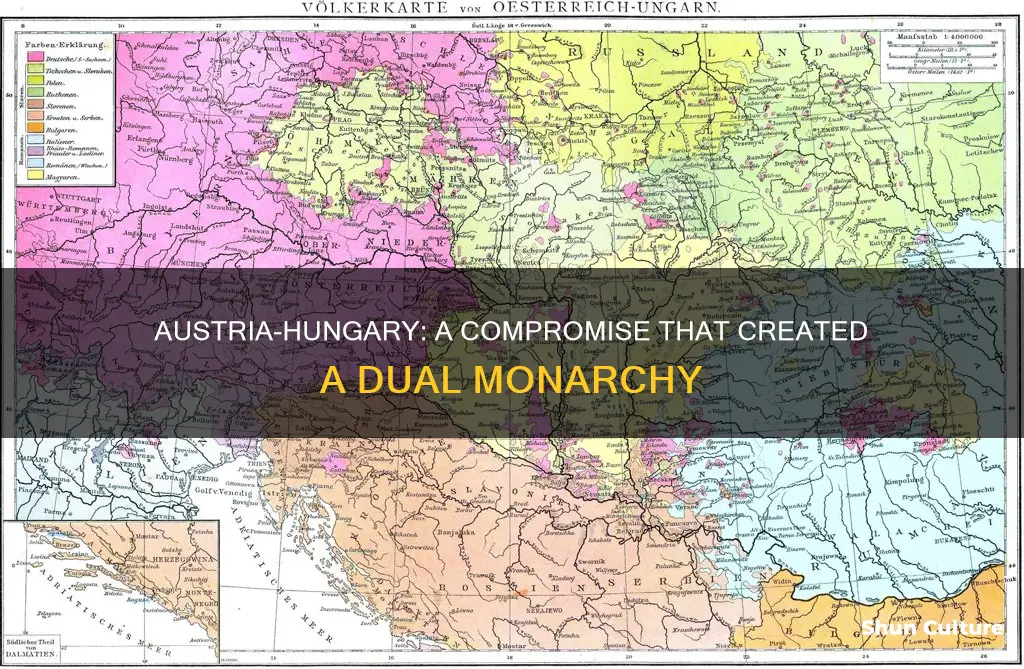

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, or Austria-Hungary, was a major European power and a multinational constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed in 1867 by a compromise agreement between Vienna and Budapest, creating a dual monarchy consisting of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary. This agreement, known as the Ausgleich, granted Hungary full internal autonomy and its own parliament, prime minister, and cabinet, while the two kingdoms shared a single monarch, who held the titles of Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary. The compromise also established a central government responsible for foreign policy, military command, and joint finance, which was composed of the emperor, both prime ministers, appointed ministers, members of the aristocracy, and representatives of the military.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name |

What You'll Learn

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise

Under the Compromise, the Kingdom of Hungary regained its traditional status and internal autonomy, with its own parliament and prime minister. The Hungarian legal and judicial systems were restored, and the old historic constitution of the Kingdom of Hungary was reinstated. Hungary agreed that the empire should remain a single great state for war and foreign affairs, with a shared foreign policy and defence, and a common currency. The two halves of the empire were united under a single monarch, who reigned as Emperor of Austria in the Austrian half and as King of Hungary in the Kingdom of Hungary.

The Austrian and Hungarian states were co-equal in power, each with its own government, constitution, and parliament. The citizens of each half were treated as foreigners in the other half. The two partner states were quite different: the Austrian half, or Cisleithania, consisted of seventeen historical crown lands and was a multinational state; the Hungarian half, or Transleithania, was dominated by Magyars, but was also multi-ethnic.

The Compromise transformed the Habsburg Monarchy into a dual system, with each half of the empire having its own distinct identity and autonomy while being united under a common monarchy. The agreement was not without its challenges, as there were disputes over shared external tariff arrangements and financial contributions to the common treasury. Despite these issues, the Compromise held for half a century until World War I, when the empire began to disintegrate due to rising nationalist movements and ethnic tensions.

Sending Amazon Gift Cards to Austria: Is It Possible?

You may want to see also

The Hungarian Parliament

The negotiations were led by Ferenc Deák on the Hungarian side and resulted in the Ausgleich, or Compromise, of 1867. This agreement established a dual monarchy, with the Austrian Emperor, Franz Joseph, also becoming the King of Hungary. While the two roles were held by the same person, Hungary was granted its own parliament and considerable autonomy in internal affairs.

In 1918, the Hungarian Parliament voted to terminate the union with Austria, effectively dissolving the Austro-Hungarian state. This came about due to rising nationalist sentiments and the desire for self-governance among the various ethnic groups within the empire. The Hungarian Prime Minister, Count Mihály Károlyi, was a prominent opponent of continued union with Austria and played a key role in the dissolution.

Austria's Monarchy: Past or Present?

You may want to see also

The Austrian Emperor

Franz Joseph's power was absolute in theory, but in practice, he was conservative and reluctant to make big decisions, often at odds with his more liberal and progressive nephew, Franz Ferdinand, who was heir to the throne. The Emperor's traditional views put him at odds with nationalist and liberal sentiments across his territories, and he was no warmonger. He often rejected demands for strong action or the deployment of the imperial army, which he guarded jealously.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a major European power, geographically the second-largest country in Europe and third-most populous. It was a relatively young nation-state, formed in 1867, with a rich mix of people and cultures. The empire was overseen by a central government responsible for foreign policy, military command and joint finance. The emperor, both prime ministers, three appointed ministers, members of the aristocracy and representatives of the military made up this government.

The empire's political organisation was complex and unusual, with each of the two monarchies continuing to exist with a degree of autonomy, their own parliament, prime minister, cabinet and domestic self-government. The two older armies, retained by the kingdoms of Austria and Hungary, were protected by their respective parliaments and received more funding and better equipment and training than the Imperial and Royal Army, which was perpetually short of qualified officers. The Imperial and Royal Army was also undermined by internal political and ethnic divisions, with Austrian officers speaking German while the majority of soldiers were of other nationalities.

Franz Joseph's wife, Empress Elisabeth, was a noted supporter of Hungarian causes, which may have influenced the emperor's decision to grant Hungary more autonomy.

Austria's Language Heritage: German Influence and Evolution

You may want to see also

The Hungarian Nobility

In the Ausgleich (compromise) of 1867, which established the dual monarchy, the Hungarian nobility secured significant autonomy for Hungary within the empire. The kingdom retained its own parliament, the National Assembly, and its own prime minister and executive government. The Hungarian nobility's influence extended beyond their own kingdom, as they held a majority in the Austro-Hungarian armed forces, providing more than half of the empire's military personnel during World War I.

During World War I, the Hungarian nobility provided significant support to the military efforts, and they were known for their patriotism and loyalty to the empire. However, the war also brought about social and economic changes that challenged the traditional power structure. The post-war period saw the rise of leftist and pacifist movements, and the Hungarian nobility faced increasing opposition from nationalist and minority groups seeking independence. Ultimately, the Hungarian nobility's influence waned as the empire collapsed in 1918 with the end of World War I and the rise of republican governments in Austria and Hungary.

Austria-Hungary's Role in Preserving the Papal States

You may want to see also

The Dual Monarchy

The official name of the state was Austria-Hungary. The rest of the empire outside of the Kingdom of Hungary was a casual agglomeration without a clear description. Technically, it was known as "the kingdoms and lands represented in the Reichsrat" or, more shortly, as "the other Imperial half". The mistaken practice soon grew of describing this nameless unit as "Austria" or "Austria proper" or "the lesser Austria"—names all strictly incorrect until the title "empire of Austria" was restricted to "the other Imperial half" in 1915.

Buying Vignettes in Austria for the Czech Republic

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Compromise of 1867, also known as the Ausgleich, was a compromise between Emperor Franz Joseph and Hungary, not between Hungary and the rest of the empire. It gave Hungary full internal autonomy and its own parliament, while the empire remained a single great state for war and foreign affairs purposes.

The Austrian Empire wanted to consolidate its heterogeneous empire and reorient its policy towards the east. The Hungarians wanted more independence and less rule from Vienna.

The empire became known as the Dual Monarchy, with two separate kingdoms, each with its own parliament, prime minister, and domestic self-government. The emperor was crowned king of both Austria and Hungary, and remained the head of state and government.

There were often jealousies, grievances, and disagreements between the two kingdoms. The empire's political organisation was complex and unusual, and the three armies (two for each kingdom and one imperial army) were divided by language barriers and a lack of qualified officers.

The assassination of the Austro-Hungarian heir, Franz Ferdinand, in 1914, sparked World War I, which led to the collapse of the empire in 1918. The empire's defeat in the war, combined with revolutions by various ethnic groups, including the Czechs, Yugoslavs, and Hungarians, brought about the end of Habsburg rule.