Prisoners at Angola, a maximum-security prison in Louisiana, are forced to work in the prison's fields for little to no pay. The prison, which sits on the site of a former slave plantation, has faced criticism and lawsuits from prisoners and human rights groups who argue that the work conditions are cruel, degrading, and dangerous. While prisoners can technically refuse to work, they face severe punishments such as solitary confinement and loss of family visitation if they do so. The issue of forced prison labor in the United States is complex and raises ethical and legal questions about the treatment of incarcerated individuals.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Prisoners' pay | 2 cents to 40 cents an hour |

| Prisoners' work | Manual labor, including hoeing, weeding, picking crops, harvesting produce |

| Work conditions | Cruel, degrading, dangerous, with little water, in extreme heat |

| Consequences of refusing to work | Sent to solitary confinement, punished |

| Prisoners' health issues | Disabilities, health conditions, heat strokes, heart attacks |

| Prisoners' rights | 8th Amendment rights to be free of cruel and unusual punishment |

| Prison's response | Provided inmates with sunscreen and pop-up tents for shade, five-minute breaks every half hour during heat alerts |

What You'll Learn

Angola prisoners are paid little to nothing for their work

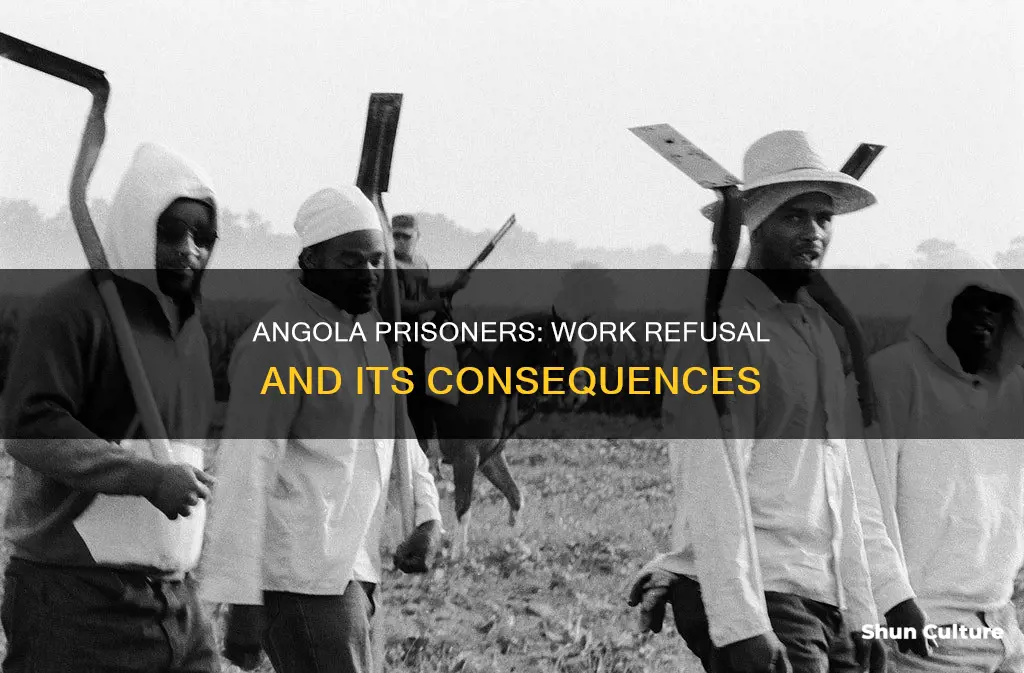

Angola, or the Louisiana State Penitentiary, is a maximum-security prison located on a former slave plantation. The prison has been the site of protests and lawsuits by prisoners who are forced to work in the prison's fields for little to no pay. In May 2018, a group of prisoners refused to perform field labour, with one prisoner, Ron, stating that they "don't want to work for free [because it's] modern-day slavery".

Prisoners at Angola are paid as little as 2 cents an hour for grueling manual labour, which can involve long hours of hoeing, weeding, and picking crops by hand in hot temperatures. According to data from the Prison Policy Initiative, prisoners in Louisiana are paid between 4 cents to $1 per hour for jobs supporting prison facilities, and up to 40 cents an hour for work on products and services sold to outside government agencies and private businesses.

The prison's location on a former slave plantation, and the fact that prisoners are forced to work in the fields for little to no pay, has led to comparisons to slavery. In a class-action lawsuit filed in September 2023, prisoners contended that the work they are forced to do serves no legitimate purpose and is purely punitive, designed to "break" incarcerated men and ensure their submission."

The issue of low or no pay for prison labour is a significant concern for prisoners at Angola, who risk severe punishment, including solitary confinement, for refusing to work or failing to meet quotas. This has led to protests and strikes, with prisoners demanding an end to what they perceive as modern-day slavery and calling for opportunities for education and rehabilitation instead of hard labour.

Angola's 2010 Election: Results and Reactions

You may want to see also

They are subject to punishment if they refuse to work

Prisoners at Angola, a maximum-security prison in Louisiana, are subject to punishment if they refuse to work. This is due to a loophole in the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery but allowed for it as punishment for a crime. As a result, Angola prisoners can be forced to work in grueling conditions for little to no pay, facing consequences such as solitary confinement if they refuse.

The prison, located on the site of a former slave plantation, has a long history of forced labor. Prisoners, most of whom are Black, engage in manual labor such as hoeing, weeding, and harvesting crops by hand under the watch of armed guards. The work is physically demanding and often done in extreme heat with inadequate access to water, rest, and shade.

In 2024, a group of prisoners refused to work, citing concerns of modern-day slavery and unfair compensation. This led to a class-action lawsuit filed by incarcerated men, contending that they were forced to work in cruel and degrading conditions for little to no pay. The lawsuit described the labor as "purely punitive" and designed to "break" the prisoners.

Angola prisoners face punishment, including solitary confinement, if they refuse to work or fail to meet quotas. This has been a longstanding issue, with historical accounts of prisoners being beaten and subjected to solitary confinement for protesting their work conditions.

The consequences of refusing to work at Angola highlight the complex dynamics of prison labor in the United States, where incarcerated individuals are stripped of their constitutional rights to be free from forced servitude. While prison work is often justified as providing skills and rehabilitation, the harsh realities of Angola's labor conditions and punishment for non-compliance raise serious ethical concerns.

Angola's Rich Cultural Heritage and Natural Beauty

You may want to see also

They are made to work in dangerous conditions

Prisoners at Angola are made to work in dangerous conditions. Inmates are forced to work in the prison's fields for little to no pay, facing cruel and degrading conditions. The prison, a former slave plantation, houses inmates in old slave quarters and forces them to work in the fields. The work involves manual labor, such as hoeing, weeding, and harvesting produce, which requires bending down in the hot sun. Inmates complain of dehydration due to a lack of water.

The conditions are especially dangerous during the summer months, with temperatures reaching up to 102 degrees Fahrenheit and heat indexes of up to 145. Inmates with disabilities or health conditions face an even higher risk of illness or injury. The presence of armed guards patrolling the fields further emphasizes the dangerous nature of the work environment.

In addition to the physical dangers, the work also takes a mental toll on the prisoners. It is described as "purely punitive" and designed to "break" the incarcerated men and ensure their submission. The work serves no legitimate penological or institutional purpose and is considered a form of modern-day slavery.

Angola has a long history of resistance to these dangerous working conditions, with prisoners organizing strikes, protests, and other acts of defiance. Despite the risks of severe punishment, including solitary confinement, inmates have continued to speak out against the exploitative and dangerous labor conditions they are subjected to.

Angola Incarceration: Exploring Sexuality Among Male Prisoners

You may want to see also

Angola is on the site of a former slave plantation

Angola, also known as the Louisiana State Penitentiary, is a maximum-security prison in Louisiana, US. It is the largest maximum-security prison in the country, with 6,300 prisoners and 1,800 staff. The prison is located on the site of a former slave plantation, named after the country of Angola, from which many enslaved people were taken before arriving in Louisiana.

The Angola Plantations, as it was known before the American Civil War, was a slave plantation owned by slave trader Isaac Franklin. The 28 square miles of land was purchased in the 1830s from Francis Rout as four contiguous plantations. After Franklin's death in 1846, his widow, Adelicia Cheatham, sold the plantations in 1880 to Samuel Lawrence James, a former Confederate major and officer.

Under the convict lease system, Major James used convicts leased from the state as workers on his plantation. With the incentive to earn money from prisoners, the state passed laws targeting African Americans, requiring payment of minor fees and fines as punishment. This pushed cash-poor men in the agricultural economy into jail and convict labor. The convict lease system was so profitable that the State of Louisiana purchased the plantation from James in 1901, initiating its own slave-style penal enterprise.

Today, Angola Prison still has the look and feel of the former plantation, with rows of crops tended by prisoners. The prison is a working farm, with prisoners cultivating and harvesting various crops, including cabbage, corn, cotton, strawberries, okra, onions, peppers, soybeans, squash, tomatoes, and wheat. Angola is also the only penitentiary in the US where inmates are allowed to run their own churches, a practice founded in the prison's history with slavery.

Portuguese Presence in Angola: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Prisoners have filed lawsuits to end the farm work

Prisoners at Angola have filed a class-action lawsuit against the state of Louisiana, calling for an end to farm work and accusing the state of cruel and unusual punishment. The lawsuit contends that prisoners have been forced to work in the prison's fields for little to no pay, facing harsh conditions and the threat of punishment for refusing to work or failing to meet quotas. This includes being sent to solitary confinement, which the lawsuit describes as "purely punitive, designed to 'break' incarcerated men and ensure their submission".

The lawsuit specifically names Angola's warden, Timothy Hooper, and officials from Louisiana's department of corrections and Prison Enterprises as defendants. It argues that the farm work serves no legitimate penological or institutional purpose and instead amounts to forced labour and modern-day slavery.

The conditions that prisoners are subjected to include working in extreme heat, with temperatures soaring past 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and facing the threat of armed guards. The lawsuit also highlights the lack of water provided to keep prisoners hydrated and cool, which has resulted in cases of heat stroke.

The suit further asserts that the field work violates the prisoners' 8th Amendment rights to be free from cruel and unusual punishment. It also challenges the 13th Amendment's exception for slavery as punishment for convicted individuals, which has allowed for the continuation of forced labour in prisons.

The prisoners are represented by legal advocacy organisations Promise of Justice Initiative and Rights Behind Bars, and they are asking the court to declare the forced work unconstitutional and to put an end to the generations-long practice of compulsory agricultural labour at Angola.

Angola's history as a former slave plantation, combined with the current conditions faced by prisoners, has brought attention to the issue of prison labour and sparked a movement to end what is perceived as modern-day slavery.

Property Investment in Angola: Foreigner's Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, prisoners at Angola can refuse to work, but they may face severe punishment for doing so, including solitary confinement.

Prisoners at Angola work long hours doing manual labor, such as harvesting produce, in extreme heat with little water and inadequate protection from the elements. They are paid very little for their work, earning as little as 2 cents an hour.

The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolished slavery but included an exception for those "duly convicted" of a crime. Correctional officials argue that work programs in prisons provide skills and a sense of purpose for inmates, reduce idleness, and reduce recidivism.