Austria and Austria-Hungary are not the same thing. Austria is a landlocked country in Central Europe with a population of around 8.95 million. It is a parliamentary representative democracy and one of the wealthiest countries in the world.

Austria-Hungary, also known as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was a multinational constitutional monarchy in Central Europe that existed between 1867 and 1918. It was formed by an agreement between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, which gave Hungary full internal autonomy while keeping the empire a single great state for war and foreign affairs purposes. The two countries shared a monarch, who was titled both Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Official Name | Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Empire, Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Österreich-Ungarn, Österreichisch-Ungarische Monarchie, Österreichisch-Ungarisches Reich, Doppelmonarchie, Dual Monarchy |

| Date of Existence | 1867 - 1918 |

| Type of State | Dual Monarchy |

| Ruling House | House of Habsburg |

| Official Languages | German, Hungarian, Czech, Polish, Ukrainian, Romanian, Croatian, Italian, Slovak, Serbian, Slovene |

| Unofficial Minority Languages | Bosnian, Rusyn, Yiddish |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Judaism, Sunni Islam |

| Capital | Vienna, Budapest |

| Area | 676,615 km² (261,243 sq mi) |

| Population Density | 78 /km² (202.1 /sq mi) |

| Currency | Gulden, Krone (from 1892) |

| Successor States | Hungarian Democratic Republic, First Czechoslovak Republic, West Ukrainian People's Republic, Second Polish Republic, State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, Kingdom of Italy, Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Ukraine |

What You'll Learn

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a constitutional monarchy

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, also known as the Dual Monarchy, was a constitutional monarchy that existed from 1867 to 1918. It was formed through the Compromise of 1867, which established a dual system wherein each half of the empire—Cisleithania (the Austrian half) and Transleithania (the Kingdom of Hungary)—had its own constitution, government, and parliament. The citizens of each half were treated as foreigners in the other.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a military and diplomatic alliance of two sovereign states, with a single monarch, Emperor Franz Joseph, who was titled both Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary. The two countries conducted unified diplomatic and defence policies, with "common" ministries of foreign affairs, defence, and finance under the monarch's direct authority.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was one of the major powers in Europe at the time, and was the second-largest country in Europe geographically, as well as the third-most populous. It was among the ten most populous countries worldwide and had the fourth-largest machine-building industry in the world.

The two partner states had distinct characteristics. Cisleithania, or the Austrian half of the empire, consisted of seventeen historical crown lands and was a multinational state that granted numerous rights to its individual nationalities. Transleithania, or the Kingdom of Hungary, was dominated by the Magyars, who made up only a small majority (54.5%) compared to other language groups. The non-Magyar ethnic groups were considered minorities and had the status of minorities, despite making up a significant portion of the population.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was dissolved in 1918, following World War I, and was succeeded by the Kingdom of Hungary and the First Austrian Republic.

Exploring Vienna: A Step-by-Step Guide to the City

You may want to see also

It was formed in 1867 after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, also known as the Ausgleich, established the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. This was a military and diplomatic alliance of two sovereign states, the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, with a single monarch. The Compromise was an agreement between the Emperor of Austria, Franz Joseph, and the Kingdom of Hungary, which had desired equal status with the Austrian Empire. It was not an agreement between Hungary and the rest of the empire.

The Compromise was formed in the aftermath of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, which had resulted in the dissolution of the German Confederation and the exclusion of Austria from German affairs. The Austrian Empire was weakened and the Hungarians saw an opportunity to remove the shackles of absolutist rule. The central government in Vienna began negotiations with the Hungarian political leaders, led by Ferenc Deák.

The Compromise established a real union between the Austrian and Hungarian states, which were co-equal in power. Each state had its own government, headed by its own prime minister, and its own parliament. However, the two countries conducted unified diplomatic and defence policies, with "common" ministries of foreign affairs and defence under the direct authority of the monarch. A third finance ministry was responsible only for financing these two "common" portfolios.

Under the Compromise, Franz Joseph surrendered his domestic prerogatives in Hungary and granted the kingdom full internal autonomy, including restoring the old historic constitution of the Kingdom of Hungary. In return, Hungary agreed that the empire should remain a single great state for purposes of war and foreign affairs, thus maintaining its dynastic prestige abroad. The Hungarians also took on a large part of the Austrian state debt.

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 was a significant development in the constitutional evolution of the Habsburg monarchy, which had previously ruled as the Austrian Empire. The Compromise turned the Habsburg domains into a dual monarchy, with the Austrian half officially referred to as "the other Imperial half" or "Cisleithania", and the Hungarian half as "Transleithania". This dual monarchy lasted until 1918, when Hungary terminated the union with Austria.

Hitler's Annexation of Austria: Prelude to War

You may want to see also

It was dissolved in 1918 after World War I

The dissolution of Austria-Hungary was a significant geopolitical event that occurred due to the growth of internal social contradictions and the separation of different parts of the empire. The immediate reasons for the collapse of the state were World War I, the 1918 crop failure, general starvation, and the economic crisis. The Austro-Hungarian Empire had been weakened over time by a widening gap between Hungarian and Austrian interests, and a history of chronic overcommitment.

By 1918, the economic situation had deteriorated, and the government had failed badly on the home front. The majority of people across central Europe lived in a state of advanced misery by the spring of 1918, and conditions worsened as food supplies dropped and the 1918 flu pandemic hit. Society was relieved, exhausted, and yearned for peace. As the Imperial economy collapsed into severe hardship and even starvation, its multi-ethnic army lost its morale and was increasingly hard-pressed to hold its line.

Nationalists within the empire became embittered as, under expanded wartime powers, the military routinely suspended civil rights and treated different national groups with varying degrees of contempt throughout the Austrian half of the Dual Monarchy. At the last Italian offensive, the Austro-Hungarian Army took to the field without any food and munition supply and fought without any political support for a de facto non-existent empire.

The Austro-Hungarian monarchy collapsed with dramatic speed in the autumn of 1918. Leftist and pacifist political movements organized strikes in factories, and uprisings in the army had become commonplace. Eventually, the German defeat and the minor revolutions in Vienna and Budapest gave political power to the left/liberal political parties.

As the war went on, ethnic unity declined, and the Allies encouraged breakaway demands from minorities. As it became apparent that the Allied powers would win World War I, nationalist movements, which had previously been calling for a greater degree of autonomy for various areas, started pressing for full independence. In the capital cities of Vienna and Budapest, the leftist and liberal movements and opposition parties strengthened and supported the separatism of ethnic minorities. The multiethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire started to disintegrate, leaving its army alone on the battlefields. The military breakdown of the Italian front marked the start of the rebellion for the numerous ethnicities who made up the empire, as they refused to keep fighting for a cause that now appeared senseless. The Emperor had lost much of his power to rule, as his realm disintegrated.

On 14 October 1918, Foreign Minister Baron István Burián von Rajecz asked for an armistice based on President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points. On 16 October 1918, Emperor Karl I of Austria and IV of Hungary proclaimed the People's Manifesto, which envisaged turning the Empire into a federal state of five Kingdoms (Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, and Polish-Galicia). However, the national groups deeply distrusted Vienna and were now determined to gain independence.

On 18 October, United States Secretary of State Robert Lansing replied that the Allies were now committed to the causes of the Czechs, Slovaks, and South Slavs. Therefore, Lansing said, autonomy for the nationalities was no longer enough, and Washington could not deal on the basis of the Fourteen Points anymore. The Lansing note was, in effect, the death certificate of Austria-Hungary.

On 24 October 1918, a Hungarian National Council prescribing peace and severance from Austria was set up in Budapest. On 28 October, a Czechoslovak committee in Prague passed a "law" for an independent state, while a similar Polish committee was formed in Kraków. On 29 October, the Croats in Zagreb declared Slavonia, Croatia, and Dalmatia to be independent, pending the formation of a national state of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs. On 30 October, the German members of the Reichsrat in Vienna proclaimed an independent state of German Austria.

The solicited armistice between the Allies and Austria-Hungary was signed at the Villa Giusti, near Padua, on 3 November 1918, to become effective on 4 November. Under its provisions, Austria-Hungary's forces were required to evacuate all territory occupied since August 1914 and some additional territories. All German forces were to be expelled from Austria-Hungary within 15 days or interned, and the Allies were to have free use of Austria-Hungary's internal communications and most of its warships.

Count Mihály Károlyi, chairman of the Budapest National Council, was appointed prime minister of Hungary by Emperor Karl on 31 October but promptly started to dissociate his country from Austria. Karl, the last Habsburg to rule in Austria-Hungary, renounced the right to participate in Austrian affairs of government on 11 November and in Hungarian affairs on 13 November.

German and Austrian: Different or Same?

You may want to see also

Austria-Hungary was geographically the second-largest country in Europe

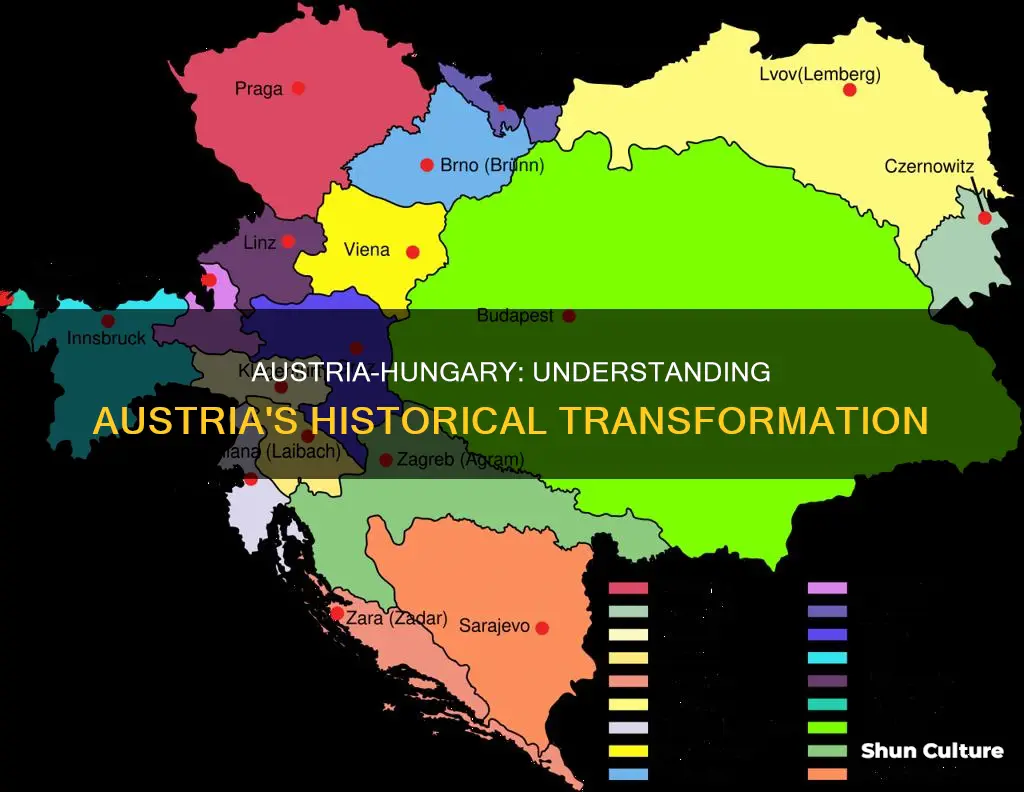

Austria-Hungary, also known as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe. It was formed in 1867 by a compromise agreement between Vienna and Budapest and lasted until 1918. It was a union of two separate kingdoms, often called the Dual Monarchy, and geographically, it was the second-largest country in Europe, spanning almost 700,000 square kilometres.

The empire was formed of the Kingdom of Hungary and the Austrian Empire, with the Emperor of Austria also being crowned the King of Hungary. The two kingdoms maintained their own parliaments, prime ministers, cabinets, and domestic self-government, with the exception of foreign policy, military command, and joint finance, which were overseen by a central government. The central government was made up of the emperor, both prime ministers, three appointed ministers, members of the aristocracy, and representatives of the military.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was one of the major powers in Europe at the time, and its population of 52 million people made it the third-most populous country on the continent. It was also among the ten most populous countries worldwide. The empire was incredibly diverse, with 11 major ethno-language groups, and its geography ranged from the mountainous Tyrol region north of Italy to the fertile plains of Ukraine and the Transylvanian mountains of eastern Europe.

The empire's military force was made up of three armies: two retained by the kingdoms of Austria and Hungary, and a newly created force called the Imperial and Royal Army. The Austro-Hungarian Empire had one of the best rail networks in Europe, which was chiefly built for military benefits.

Austria's Flag: A Simple Tricolor Design

You may want to see also

It was a multi-ethnic and multi-lingual state

After searching for "are Austria and Austria-Hungary the same thing," I can confirm that they are not the same entity. Austria refers to the modern-day Republic of Austria, a sovereign country in Central Europe. On the other hand, Austria-Hungary, or more formally known as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was a vast empire that existed from 1867 to 1918. It was a dual monarchy composed of two constituent parts: the Kingdom of Hungary and the Kingdom of Austria, with the Emperor of Austria serving as the head of state for both realms.

Now, focusing on the statement, "It was a multi-ethnic and multi-lingual state":

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was indeed a diverse and multicultural entity, encompassing multiple ethnic and linguistic groups within its borders. This was a direct result of the empire's expansionist policies and the acquisition of territories through wars, marriages, and dynastic inheritance over centuries. The empire included not only the current-day territories of Austria and Hungary but also significant portions of modern-day Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, parts of Poland, Serbia, Romania, and Ukraine, among others.

This vast expanse of territories led to an incredible diversity of peoples and cultures. The two most prominent ethnic groups were the Germans (including Austrians) and the Hungarians, but there were also substantial numbers of Slavs (such as Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, and South Slavs), Romanians, and Italians, among others. Each of these groups had their own distinct language, culture, and, in some cases, religious traditions, which contributed to the empire's rich tapestry of identities.

The empire officially recognized and promoted the use of multiple languages. German, Hungarian, and Croatian were the three most widely spoken and recognized languages in the empire. German was the dominant language in the Austrian part of the empire, especially in administration and higher education, while Hungarian held a similar status in the Kingdom of Hungary. Croatian, and to some extent, other Slavic languages, were also recognized, particularly in areas with significant South Slavic populations, such as Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The multi-ethnic nature of the empire presented both opportunities and challenges. On the one hand, it fostered a vibrant cultural exchange and contributed to the development of arts, literature, and philosophy. On the other hand, the competing national interests and aspirations of the various ethnic groups often led to tensions and conflicts. Nationalists from different groups frequently clashed, and the empire struggled to balance the demands for autonomy and self-governance. This struggle ultimately contributed to the empire's downfall after its defeat in World War I, as the victorious powers sought to redraw the map of Europe along more nationally defined borders.

In conclusion, the Austro-Hungarian Empire's multi-ethnic and multi-lingual character was a defining feature that shaped its history and legacy. It left a profound impact on the region, influencing the political, cultural, and social landscapes of Central and Eastern Europe well into the 20th century. The empire's rise and fall offer valuable insights into the complexities of managing diverse populations and the ongoing quest for national self-determination.

The Austrian Alps' Edelweiss Song: Cultural Icon or Myth?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Austria-Hungary, also known as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was a constitutional monarchy in Central Europe that existed between 1867 and 1918. It was formed through a compromise between Austria and Hungary, which gave Hungary full internal autonomy and its own parliament, while the empire remained a single great state for war and foreign affairs.

The Austrian Empire was the official designation of the territories ruled by the Habsburg monarchy from 1804 until 1867, when it became part of Austria-Hungary.

The Austrian Empire was a unitary state, whereas Austria-Hungary was a dualistic state with two parliaments: one for Austria and one for Hungary. Each parliament managed its own domestic affairs, while a joint cabinet handled foreign affairs, military affairs, and finances.

Austria and Hungary were two semi-independent halves of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. While they had their own parliaments and authority over most internal affairs, they shared a head of state: the Emperor of Austria was also the King of Hungary.

World War I brought about the end of the Habsburg rule in Austria-Hungary. The empire was dissolved in 1918, and its territories were reorganised into various independent states, including Austria and Hungary, which became republics and exiled the Habsburg family.