The Austro-Hungarian Empire, also known as the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, was formed in 1867 by the Compromise of 1867, also known as the Ausgleich. The empire was a dual monarchy, consisting of two independent states, Hungary and Austria, joined together by a common ruler, a common ministry for foreign affairs, a joint military, a common currency, and a common trade policy. The empire was formed in the aftermath of the Austro-Prussian War and lasted until the end of World War I in 1918.

What You'll Learn

- The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a dual monarchy formed by the Compromise of 1867

- It was a continental empire, spanning almost 700,000 square kilometres and containing 52 million people

- The empire was ruled by Emperor Franz Joseph, who was both head of state and government

- The empire was made up of 11 major ethno-language groups, including Germans, Hungarians, and Slovaks

- It was a powerful, modernised military force, though its effectiveness was undermined by internal political and ethnic divisions

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a dual monarchy formed by the Compromise of 1867

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, also known as the Dual Monarchy, was formed in 1867 following the Compromise of 1867. This agreement established a dual monarchy, consisting of two sovereign states, the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, with a single monarch, Emperor Franz Joseph. The Compromise of 1867 was a result of negotiations between the central government in Vienna and Hungarian political leaders, led by Ferenc Deák.

Prior to the Compromise, the Kingdom of Hungary had been under the rule of the Habsburg Monarchy, which also controlled the Austrian Empire. However, following the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, the Habsburgs instituted an 18-year-long period of military dictatorship and absolutist rule over Hungary. The Compromise of 1867 put an end to this dictatorship and restored Hungary's traditional status and historic constitution.

Under the Compromise, the Austrian and Hungarian states had separate constitutions, governments, and parliaments, with each state co-equal in power. The two countries conducted unified diplomatic and defence policies, with common ministries of foreign affairs, defence, and finance under the direct authority of the monarch. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a multi-national constitutional monarchy, with the Emperor of Austria also being crowned King of Hungary.

The Compromise of 1867 transformed the Habsburg Monarchy into a dual system, with each half of the empire having its own distinct identity and autonomy. The Austrian half, known as Cisleithania, consisted of seventeen historical crown lands and was a multinational state, granting numerous rights to its various nationalities. The Hungarian half, or Transleithania, was dominated by the Magyars, but also included other ethnic groups such as Slovaks, Romanians, and Serbs.

The Compromise of 1867 was a significant event in the history of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, establishing the dual monarchy and providing a framework for the empire's governance and relations between the Austrian and Hungarian states. The empire lasted until 1918, when it was dissolved following World War I and the breakup of the dual monarchy into separate nations.

The Austrian Roots of the Croissant

You may want to see also

It was a continental empire, spanning almost 700,000 square kilometres and containing 52 million people

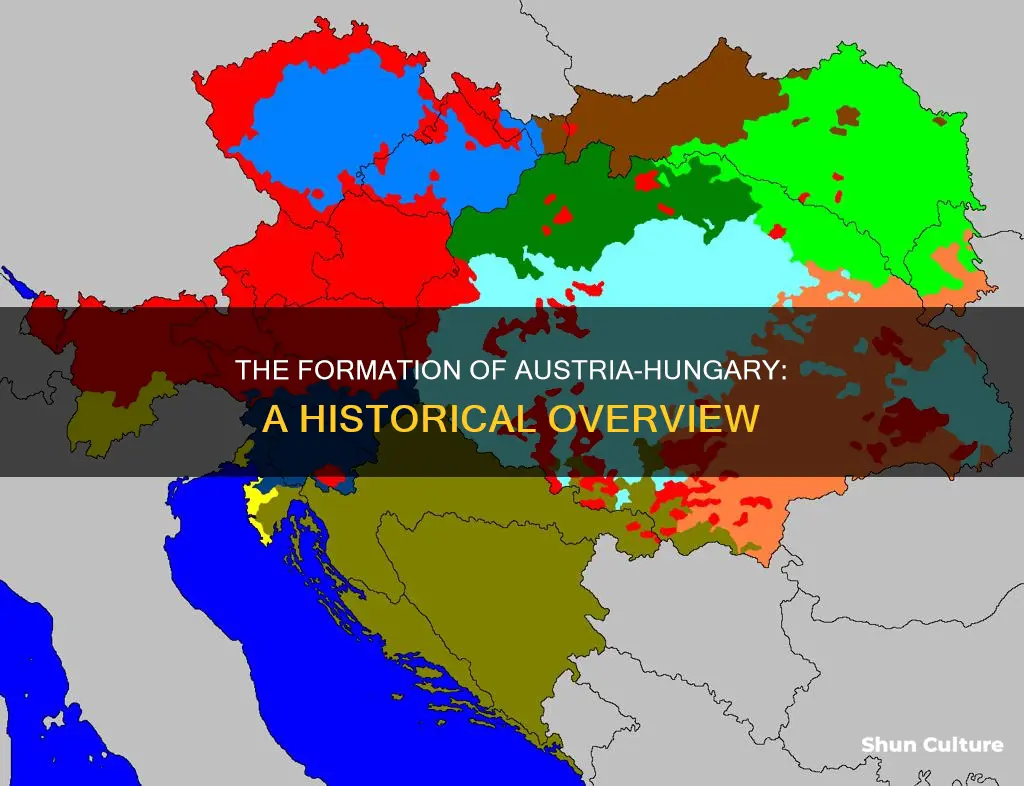

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria-Hungary, was a vast and diverse entity that existed from 1867 to 1918. Formed through the union of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, it encompassed a significant portion of Central and Eastern Europe. With a total area of nearly 700,000 square kilometres, it was an extensive empire on the continent, ranking among the largest in European history. The empire boasted a substantial population, with approximately 52 million people calling it home. This made it one of the most populous regions in the world during that era.

The empire's expanse stretched far and wide, incorporating a diverse array of territories and peoples. It included modern-day Austria, Hungary, and significant portions of what are now the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, Ukraine, Romania, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy. The empire's reach even extended to include parts of modern-day Montenegro, Albania, and Greece. This vast territory was not a contiguous landmass but rather a collection of territories, some of which were geographically disconnected from the empire's heartland.

The population of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was incredibly diverse, comprising numerous ethnic and linguistic groups. Among the most prominent were the Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Romanians, and South Slavs, including Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. Each of these groups had their distinct cultures, traditions, and, in many cases, aspirations for national self-determination. Managing this multi-ethnic empire presented significant challenges, and ensuring the loyalty and cohesion of its diverse population was a constant endeavour.

The empire's size and population density varied considerably across its territories. While some areas, such as the industrial regions of Bohemia (now the Czech Republic) and the fertile plains of Hungary, were densely populated, other regions, particularly the mountainous areas and frontier lands, had lower population densities. The empire's urban centres, including Vienna, Budapest, Prague, Krakow, and Trieste, were bustling hubs of cultural and economic activity, attracting people from across the empire and beyond.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire's vast expanse and substantial population endowed it with significant economic and military power. It possessed abundant natural resources, including fertile agricultural lands, vast forests, and mineral deposits. Its industries, particularly in the fields of arms manufacturing, machinery, and textiles, were well-developed. The empire's size and central location in Europe also gave it strategic importance, influencing the balance of power on the continent.

In summary, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, spanning almost 700,000 square kilometres and housing 52 million people, was a colossal entity of its time. Its continental reach and diverse population presented both opportunities and challenges, shaping the empire's history and its place in the broader context of European politics and power dynamics. The legacy of this empire continues to be studied and understood, offering valuable insights into the complexities of empire-building and the forces that shape our world today.

Austrian Economics: Understanding the Free Market Philosophy

You may want to see also

The empire was ruled by Emperor Franz Joseph, who was both head of state and government

The Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary was formed in 1867, through a constitutional compromise between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary. This compromise established a unique form of government, with a complex power-sharing arrangement, and at its head was Emperor Franz Joseph.

Emperor Franz Joseph was the embodiment of the empire's power structure, serving as both its head of state and head of government. As the emperor-king, he held immense authority and played a pivotal role in shaping the policies and direction of the empire. Franz Joseph's reign lasted for nearly 68 years, making him one of the longest-serving monarchs in European history, and his tenure had a profound impact on the course of Austrian and Hungarian history.

As the emperor, Franz Joseph was the ultimate authority in the Austrian half of the Dual Monarchy. He appointed the Prime Minister and played an active role in shaping the country's foreign and domestic policies. The emperor also held significant influence over the judiciary, as he appointed the judges and had the power to veto legislative decisions. In Hungary, while the country had its own parliament and government, Franz Joseph still held the position of king, giving him a symbolic role and certain constitutional powers, including the right to appoint the Hungarian Prime Minister.

Franz Joseph's style of leadership was characterized by his strong belief in the divine right of monarchs and his commitment to maintaining law and order. He was known for his conservative views and often clashed with the liberal and nationalist movements that were gaining traction across Europe during his reign. Despite facing significant challenges, including the rise of nationalism and ethnic tensions within the empire, as well as external pressures from other European powers, Franz Joseph remained steadfast in his commitment to preserve the integrity and stability of the empire.

Austria's Neighbors: Who Are They?

You may want to see also

The empire was made up of 11 major ethno-language groups, including Germans, Hungarians, and Slovaks

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a multi-national and multi-lingual constitutional monarchy in Central Europe. It was formed in 1867 as a compromise that gave the Kingdom of Hungary almost equal footing within the Austrian Empire. The empire was made up of 11 major ethno-language groups, including Germans, Hungarians, and Slovaks.

The empire was officially called Austria-Hungary, and it was a union between the Austrian Empire ("Lands Represented in the Imperial Council", or Cisleithania) in the western and northern half, and the Kingdom of Hungary ("Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen", or Transleithania) in the eastern half. The two countries shared a single monarch, who was titled both Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary.

The ethno-linguistic composition of the empire was diverse and complex. According to the 1910 census, 23% of the empire's citizens spoke German as their mother tongue, while 20% spoke Hungarian. Other significant language groups included Czech (13%), Polish (10%), Ruthenian (Ukrainian) (8%), Romanian (6%), Croatian (5%), Slovak (4%), Serbian (4%), Slovene (2%), and Italian (2%). Additionally, 5% of the population spoke other languages, including Bulgarian, Bunjevac (a Štokavian dialect of Croatian), and Romani.

The recognition of the various language groups and their rights was an important aspect of the empire's administration. The liberal constitutions drafted in both Cisleithania and Transleithania guaranteed equal rights for all races and the right to use and preserve their own language and culture. In Cisleithania, Article 19 of the Basic State Act of 1867 stated:

> "All races of the empire have equal rights, and every race has an inviolable right to the preservation and use of its own nationality and language. The equality of all customary languages in school, office and public life, is recognized by the state. In those territories in which several races dwell, the public and educational institutions are to be so arranged that, without applying compulsion to learn a second country language, each of the races receives the necessary means of education in its own language."

In Transleithania, the 1868 Hungarian Law on the Equality of Nationalities stated that all citizens of Hungary formed a single indivisible nation, and that the official use of various languages would be determined by the unity of the country and practical considerations. This law gave linguistic minorities the right to establish their own schools and choose their language of instruction.

The complexity of the empire's ethno-linguistic composition and the recognition of minority rights presented both opportunities and challenges for the administration. While the legal framework was designed to fairly govern the diverse territory, some minority groups felt that the concessions were not enough. The Hungarians, for example, sought greater autonomy and eventually terminated the union with Austria in 1918, leading to the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

International Driving in Austria: License Requirements Explained

You may want to see also

It was a powerful, modernised military force, though its effectiveness was undermined by internal political and ethnic divisions

The Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary was formed in 1867, through the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, which established a unique constitutional union between the Empire of Austria and the Kingdom of Hungary. This union transformed the Austrian Empire, which had been founded in 1804, into a dual monarchy, recognizing the autonomy of the Hungarian kingdom while uniting the two states under a common ruler, Emperor Franz Joseph I. The Compromise aimed to address the longstanding tensions and aspirations of the Hungarian nobility, who sought greater autonomy, and it marked a significant shift in the structure and nature of the Habsburg realm.

The creation of Austria-Hungary had profound implications for the military forces of both countries, leading to the formation of a joint military command structure. Indeed, the Austro-Hungarian Army became a formidable power in Europe, known for its professionalism, discipline, and modernization drives. Emperor Franz Joseph I, who had served as a military commander early in his reign, placed great emphasis on the expansion and modernization of the armed forces, seeking to create a cohesive and powerful military machine.

The Austro-Hungarian Army underwent significant reforms and modernization efforts, particularly in the latter part of the 19th century. Military spending increased, and new technologies were embraced, including the introduction of breech-loading rifles, machine guns, and advancements in artillery. The military leadership recognized the importance of modernization and strove to keep pace with other European powers, such as Prussia and France, in terms of military innovation and tactical doctrine.

However, despite the efforts to create a unified and powerful military, the Austro-Hungarian Army faced significant internal challenges due to the political and ethnic complexities inherent in the Dual Monarchy. The army itself reflected the multi-ethnic nature of the empire, with soldiers hailing from a diverse range of backgrounds, including Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Poles, Croats, and Slovaks, among others. Language barriers and cultural differences often created communication issues and hindered unit cohesion, affecting the overall effectiveness of the force.

Moreover, political divisions and competing national aspirations within the empire also undermined the unity and cohesion of the military. The Hungarian leadership, for instance, often sought to assert its influence over military matters, reflecting the ongoing power struggle between the Austrian and Hungarian halves of the Dual Monarchy. These internal tensions and the need to balance the interests of various ethnic groups made military decision-making and policy implementation complex and cumbersome.

The effectiveness of the Austro-Hungarian Army was further hampered by the empire's inability to fully resolve the issue of national identities and loyalties. While many soldiers fought with bravery and loyalty, the underlying tensions and competing loyalties within the empire meant that the military's effectiveness was never fully realized. These internal divisions would ultimately contribute to the collapse of the empire in the aftermath of World War I, as the centrifugal forces of nationalism and self-determination pulled the diverse peoples of the empire apart.

Austrian Delights: What to Buy When Visiting Austria

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Austria-Hungary was formed in 1867 by the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, also known as the Ausgleich.

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise was a deal struck between the Austrian and Hungarian parliaments that created a dual monarchy. This meant that while the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph also became the King of Hungary, the two territories retained considerable autonomy, with their own parliaments, prime ministers, cabinets, and domestic self-government.

The Compromise created a powerful European state, which was the second-largest by territory and third-largest by population. It was a multi-national constitutional monarchy, with a diverse mix of people and cultures.

Austria-Hungary was on the losing side of World War I and was dissolved in 1918 as a result. The empire was split into separate entities based on nationality: Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Transylvania (which became part of Romania) were created.