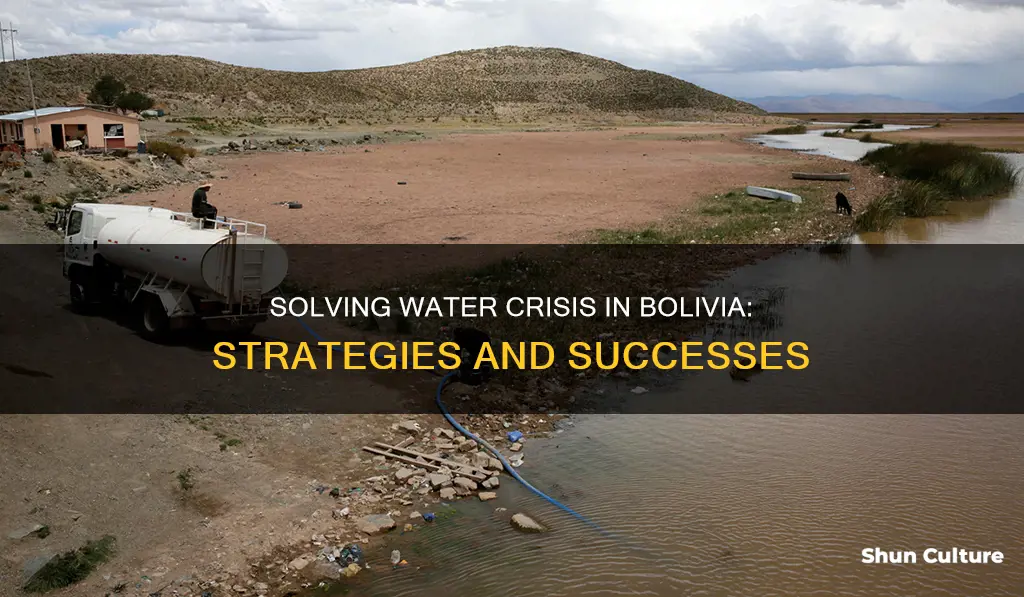

Bolivia's water crisis has been a long-simmering issue, with the country facing a deepening water crisis that threatens to leave millions without secure, safe drinking water. The Cochabamba Water War of 2000, sparked by the privatisation of the city's water supply, was a significant moment in the fight for the right to water. While the water supply was returned to public hands, Bolivia continues to battle severe water problems, with climate change posing a significant threat to the country's water security. The country is making efforts to improve water planning and management, but it still faces challenges, including low access to water and sanitation, especially in rural areas.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Increase in sectoral investment | 90% of the total population had access to "improved" water in 2015 |

| Water committees | Citizen action to manage water resources, climatology and emergency response actions |

| Water War in Cochabamba | Protests against privatisation of water supply |

| WEAP tool | First-ever comprehensive model of Bolivia's rivers, lakes and streams |

| National water balance | A uniform dataset to inform water planning in the regions |

| Water for Life | A new water and sanitation services law |

What You'll Learn

The Cochabamba Water War

Background

Bolivia, facing economic instability, sought financial aid from the World Bank in 1985. The World Bank required the privatisation of the country's railroads, airlines, telephone system, and oil industry, as well as the privatisation of water. At the time, Cochabamba's waterworks were owned by the state agency SEMAPA, which was inefficient, costly, and unable to meet the growing demand.

Protests

In September 1999, after closed-door negotiations, the Bolivian government signed a $2.5 billion contract with Aguas del Tunari, a multinational consortium of private investors, to privatise Cochabamba's water system. Aguas del Tunari was the sole bidder for the contract, which granted them a 40-year concession to "provide water and sanitation services to the residents of Cochabamba, as well as generate electricity and irrigation for agriculture." The consortium was guaranteed a minimum annual return of 15% on its investment.

To meet the terms of the contract, Aguas del Tunari drastically raised water rates, in some cases tripling water bills. This sparked widespread protests, largely organised through the Coordinadora (Coalition in Defense of Water and Life), a community coalition. The protests began in January 2000 and continued throughout the year, with tens of thousands of people taking part. The demonstrators included peasant irrigators, retired unionised factory workers, Bolivian citizens, pieceworkers, sweatshop employees, street vendors, anarchists, and the city's growing population of homeless street children.

Outcome

The protests culminated in a general strike that shut down Cochabamba for four days. On April 8, 2000, the government of Hugo Banzer declared a state of siege, suspending some constitutional guarantees and allowing for the detention of protest leaders without a warrant. The protests turned violent, with police using tear gas, rubber bullets, and live ammunition against the demonstrators, who threw rocks and Molotov cocktails. A 17-year-old boy, Victor Hugo Daza, was shot and killed by a Bolivian Army captain. Continuing clashes between demonstrators and law enforcement led to internal exile, injuries, and deaths.

On April 10, 2000, the national government reached an agreement with the Coordinadora to reverse the privatisation. The executives of Aguas del Tunari left Cochabamba, and the privatisation law was revoked. The water supply was returned to public hands, marking a significant victory for the people of Cochabamba and a symbol of the fight for the right to water in Latin America.

La Paz, Bolivia: A City That Defies Heights

You may want to see also

Increased investment in water and sanitation coverage

Bolivia has made significant strides in improving its drinking water and sanitation coverage since 1990, largely due to increased investment in the sector. However, the country continues to face challenges and still has the lowest coverage levels on the continent.

The Role of Investment

The Bolivian government has recognised the need for substantial investment to increase coverage and address the sector's issues. In 2008, the Evo Morales administration published a National Basic Sanitation Plan, which outlined the investments required to achieve its targets of 90% access to water and 80% access to sanitation by 2015. These targets came with a price tag of US$283 million per year, including investments for wastewater reuse and adapting to climate change.

Historical Context

Bolivia's water and sanitation sector has a history of privatisation and political instability, which have impacted coverage and service quality. In the 1990s, under the mandate of President Hugo Banzer, the sector was privatised through concessions to foreign private companies in Cochabamba and La Paz/El Alto. These concessions were met with widespread protests, known as the Cochabamba Water War, due to the resulting increase in water prices. The protests led to the termination of the concessions in 2000 and 2006, respectively, and a reversal of privatisation policies.

Current Challenges and Future Prospects

Despite increased investment and efforts to improve water planning, Bolivia continues to face water supply issues. Droughts, shrinking glaciers, and management challenges threaten the country's water security. In 2016, Bolivia experienced its worst drought in 25 years, affecting 125,000 families and 283,000 hectares of agriculture. The country's vulnerability to climate change and frequent changes in government make it difficult to implement long-term, sustainable policies.

To address these challenges, Bolivia has taken steps to improve water planning and management. The Ministry of Environment and Water developed a uniform dataset, the "national water balance," to inform regional water planning. Additionally, Bolivia has engaged in international collaborations, such as with SEI, to create comprehensive models of its water resources and build capacity for better water management. These efforts are crucial for ensuring Bolivia's water security and providing access to safe drinking water and sanitation for its citizens.

Sucre, Bolivia: Airport Accessibility and Travel Options

You may want to see also

The Water Ministry and Evo Morales government

Bolivia's Water Ministry was created in 2006, with Evo Morales nominating a leader of the protests in El Alto against Aguas de Illimani as the country's first water minister. The Water Ministry was tasked with integrating the functions of water supply and sanitation, water resource management, and environmental protection.

Morales, who was elected president in 2005, emphasised the importance of nationalism, anti-imperialism, and anti-neoliberalism in his inaugural speech. He also immediately reduced his presidential wage and that of his ministers by 57% to $1,875 a month. Morales' government worked towards the implementation of left-wing policies, focusing on the legal protections and socioeconomic conditions of Bolivia's previously marginalised indigenous population, and combating the political influence of the United States and resource-extracting multinational corporations.

In 2009, the Morales government recognised the right to access water as a human right in Bolivia, and it was exempted from the possibility of privatisation. The Bolivian government successfully obtained recognition of this right by the United Nations General Assembly in 2010.

However, Bolivia continues to face water scarcity issues. In 2016, the country suffered its worst drought in 25 years, which led to water rationing in La Paz and El Alto. The drought was caused by a combination of climate change and a rural exodus. In El Alto, for example, the population grew by 30% between 2001 and 2012 and is expected to reach two million by 2050.

The Morales government has been criticised for its mismanagement of the water crisis. The government has failed to monitor and regulate mining companies' compliance with restricted water use and treatment of wastewater. Additionally, government mismanagement is an issue in public water administration, with inefficiencies and corruption impeding the renewal of piping systems.

The Water Ministry has also faced challenges due to frequent reorganisations and institutional instability, with six changes in leadership since its creation. Critics argue that the ministry operates as a loose federation of sub-ministry fiefdoms rather than a coherent organisation, and it suffers from overlapping jurisdictions with other cabinet ministries.

Despite these challenges, the Morales government has made significant progress in some areas. For example, the government announced that Bolivia would meet its overall Millennium Development Goal for access to safe drinking water three years ahead of schedule, with 88% overall coverage achieved in 2010. However, there are still significant disparities between urban and rural areas, with potable water access rates in rural and peri-urban zones lagging far behind those in urban areas.

Overall, the recent droughts have had a serious impact on Evo Morales' popularity and have fostered popular resentment against his government.

Malaria Tablets: Are They Necessary for Bolivia Travel?

You may want to see also

The National Plan for Basic Sanitation Services

The plan sets targets of 90% access to water and 80% access to sanitation by 2015. To achieve these targets, the plan estimates that investments of US$283 million per year are needed. These figures include investments for the reuse of wastewater and to adapt to climate change.

The quality of service in the majority of the country's water and sanitation systems is low. In 2000, according to the WHO, only 26% of urban systems disinfected water, and only 25% of the collected wastewater was treated. The plan aims to improve the quality of service and promote sustainability in the sector.

The plan also addresses the issue of low access to sanitation and water in rural areas. It seeks to increase coverage and improve the quality of water and sanitation services in these areas. This includes improving access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation for the 3 million people in rural areas who lack water security and the 5 million who do not have access to adequate sanitation.

Furthermore, the plan aims to address the issue of insufficient and ineffective investments in the sector. It calls for a substantial increase in investment financing to improve coverage and achieve the targets set out in the plan. The plan also seeks to improve water planning and build capacity in the regions to better manage their water resources and plan for future developments.

Bolivian Forests: Global Cover and Conservation Efforts

You may want to see also

The Water Evaluation And Planning (WEAP) system

WEAP operates on the basic principle of a water balance and can be applied to municipal and agricultural systems, a single watershed, or complex transboundary river basin systems. It can simulate a broad range of natural and engineered components of these systems, including rainfall runoff, baseflow, and groundwater recharge from precipitation. It also enables sectoral demand analyses, water conservation, water rights and allocation priorities, reservoir operations, and hydropower generation.

One of the key advantages of the WEAP system is its ability to facilitate stakeholder engagement. Its transparent structure encourages the participation of diverse stakeholders in an open process, ensuring that a wide range of perspectives and interests are considered in water resources planning. This feature promotes inclusivity and helps build consensus in water management decisions.

The WEAP system offers a comprehensive set of features and capabilities. It calculates water demand, supply, runoff, infiltration, crop requirements, flows, and storage. It also addresses pollution generation, treatment, discharge, and instream water quality under varying hydrologic and policy scenarios. Additionally, WEAP evaluates a full range of water development and management options, taking into account multiple and competing uses of water systems.

The system also incorporates a user-friendly interface, with a graphical drag-and-drop GIS-based interface that allows for flexible model output in the form of maps, charts, and tables. This makes it accessible and intuitive for users to interact with the data and analyse different scenarios. Furthermore, WEAP has dynamic links to other models and software, such as QUAL2K, MODFLOW, MODPATH, PEST, Excel, and GAMS, enabling the integration of additional data and tools as needed.

Exploring Bolivia's Three Diverse Regions

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bolivia faces a deepening water crisis, with around three million people in rural areas lacking water security and five million without access to adequate sanitation.

The water crisis in Bolivia has been caused by a combination of factors, including shrinking glaciers, extreme droughts, and management challenges. Political and institutional instability, as well as the impact of climate change, have also contributed to the issue.

There have been some efforts to improve water planning and build capacity in the regions. For example, the country has developed a uniform dataset, called the "national water balance", to inform water planning. Additionally, civil society organisations have played a crucial role, with "water committees" promoting water culture and community action.

The Cochabamba Water War, also known as the Bolivian Water War, was a series of protests that took place in Cochabamba, Bolivia's fourth-largest city, between December 1999 and April 2000. The protests were in response to the privatisation of the city's municipal water supply company, SEMAPA, which led to drastic increases in water rates. The demonstrations culminated in a week of clashes with police, resulting in several deaths, including that of 17-year-old Hugo Victor Daza. The national government eventually agreed to reverse the privatisation.

Bolivia is one of the most threatened countries by climate change. The average temperature in the country is rising and is projected to increase by up to 2 °C by 2030 and 5-6 °C by 2100. This, combined with deforestation, has led to severe flooding and intense droughts, further exacerbating water scarcity.