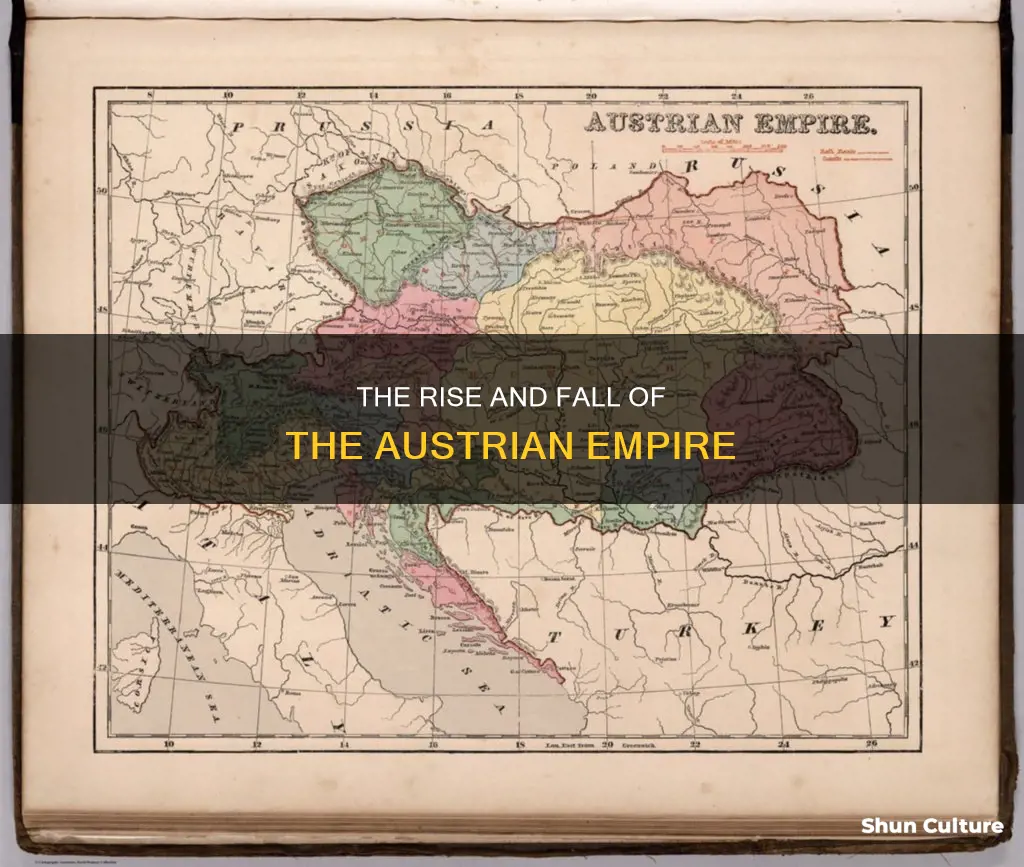

The Austrian Empire, also known as the Empire of Austria, was a European great power from 1804 to 1867. It was created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs, and it was the third most populous monarchy in Europe at the time. The empire was formed in response to Napoleon's declaration of the First French Empire, and it remained part of the Holy Roman Empire until its dissolution in 1806. After the fall of Napoleon, Austria became the leader of the German states once more, but this leadership was short-lived. The Austro-Prussian War of 1866 resulted in Austria's expulsion from the German Confederation, and in 1867, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise was adopted, joining the Kingdom of Hungary and the Empire of Austria to form Austria-Hungary, bringing an end to the Austrian Empire.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Official Name | Austrian Empire |

| Years of Existence | 1804-1867 |

| Reason for Creation | Threat of Napoleon |

| First Emperor | Franz I |

| Population Ranking in Europe | Third |

| Geographical Size Ranking in Europe | Third |

| Result of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 | Formation of Austria-Hungary |

| Result of the Napoleonic Wars | Eventual Defeat of Napoleon |

| Result of the First World War | Dissolution of the Austrian Empire |

What You'll Learn

The threat of Napoleon

Napoleon's ambitions posed a significant challenge to the Austrian Empire, leading to several conflicts and territorial losses for the Austrians. In 1805, Napoleon beat the Austrians and Russians at the Battle of Austerlitz. As a result, Franz ceded various possessions to the French Emperor and his allies, including Venice to Napoleon's Italian kingdom, and Tirol to Bavaria. The French victory at Austerlitz also encouraged rulers of certain imperial territories to ally themselves with Napoleon and assert their independence from the Empire.

In 1806, Napoleon established the Confederation of the Rhine, a collection of German states under French hegemony. This marked a significant blow to the Holy Roman Empire as these German states left its political grouping. As a result, in August 1806, Franz abdicated as Holy Roman Emperor and dissolved the Holy Roman Empire, retaining his position as Emperor of the Austrian Empire.

Despite the creation of the Austrian Empire as a contingency plan, Napoleon's expansionist efforts continued, and the Austrians struggled to maintain their territory. In 1809, Austria launched a campaign to liberate neighbouring countries from Napoleon's rule, inspired by the rebellious Spaniards' success. However, Napoleon once again defeated the Austrians and captured Vienna. This led to the Treaty of Schönbrunn in October 1809, where the monarchy surrendered more territory but remained in existence.

The ongoing conflicts with France resulted in peace treaties that further reduced Habsburg territories. The marriage of Napoleon to Franz's eldest daughter, Marie Louise, in 1810, briefly cemented an alliance between the two empires. However, the Austrian Empire continued to face territorial losses and struggled to maintain its influence due to Napoleon's expansionist policies and military successes.

Austria and Germany: Two Nations, One History

You may want to see also

The rise of nationalism

The Austrian Empire was a diverse, multi-ethnic state, and the rise of nationalism in the 19th century would pose a significant threat to its stability. The forces of nationalism would ultimately play a key role in the Empire's transformation into the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1867 and its eventual dissolution in 1918.

German Nationalism

One of the most prominent nationalist movements in the Austrian Empire was German nationalism, which sought to unite all ethnic Germans into a single nation-state. This movement, which arose in the 19th century, was particularly strong in the German-speaking parts of the Empire and advocated for close ties with Germany, which was seen as the nation-state for all ethnic Germans. German nationalists within the Empire wanted to be part of a "Greater Germany" that included German-speaking territories outside of the Empire's borders.

The German National Movement, which began with the revolutions of 1848, sought to entrench German ethnic identity within the Empire and implement anti-Semitic and anti-clerical policies. They were opposed by other ethnic groups within the Empire, such as the Serbs, Czechs, Italians, Croats, Slovenes, and Poles, who demanded political, economic, and cultural equality. The struggle between these ethnic groups defined the social and political landscape of the Empire from the 1870s until its dissolution after World War I.

Austrian Nationalism

Austrian nationalism, which originally developed as a cultural movement emphasising a Catholic religious identity, also posed a challenge to the unity of the Austrian Empire. Austrian nationalists opposed unification with Protestant-majority Prussia, seeing it as a threat to the Catholic core of Austrian national identity and a challenge to the rule of the Habsburgs.

During the interwar period, Austrian nationalism became more pronounced as Austrians sought to distance themselves from the German identity due to its association with Nazism. After World War II, proponents of an Austrian nation emphasised the non-Germanic heritage of Austrian culture, including Celtic, Illyrian, Roman, Slavic, and Magyar influences.

Other Nationalist Movements

In addition to German and Austrian nationalism, other nationalist movements also emerged within the Austrian Empire. For example, the rise of Bavarian nationalism after World War I challenged the new Austrian Republic, with proposals for Austria to join Bavaria. Additionally, the South Slav people, including Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, were drawn to the growing power of Serbia, posing an existential threat to the Empire as many of these people lived within its borders.

The rise of these various nationalist movements ultimately contributed to the dissolution of the Austrian Empire, as ethnic groups sought to form their own nations and gain independence from imperial rule.

Mozart's Austrian Identity: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

World War I

The Austrian Empire, also known as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was one of the first nations to declare war at the onset of World War I. The empire's involvement in the war began with the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, on June 28, 1914. Austria-Hungary accused Serbia of plotting the assassination and, with the backing of its allies, the German Empire and the Ottoman Empire, invaded Serbia in July 1914. This marked the beginning of World War I, as Russia mobilized in support of Serbia, triggering a series of counter-mobilizations.

During the war, the Austro-Hungarian Empire fought on multiple fronts, including Serbia, the Eastern Front, Italy, and Romania. Despite heavy casualties and setbacks, particularly on the Italian front, the empire managed to occupy Serbia in 1915 and force Romania out of the war in 1917. However, the strain of the war took its toll, and the empire faced severe economic challenges, food shortages, and growing nationalist sentiments among its diverse ethnic groups.

By late 1916, Emperor Karl I of Austria-Hungary sought peace terms from the Allies, but these initiatives were vetoed by Italy, which had been promised territorial concessions in return for joining the Allies in 1915. The empire's position further deteriorated as nationalist movements within its borders gained momentum, encouraged by the Allies' support for breakaway demands from minorities. The Lansing Note of October 18, 1918, marked a turning point, as the United States signaled its commitment to the causes of the Czechs, Slovaks, and South Slavs, effectively endorsing their aspirations for independence.

The final months of the war saw a rapid dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. On October 24, 1918, a Hungarian National Council was established, advocating for peace and separation from Austria. This was followed by a series of declarations of independence by various ethnic groups, including Czechoslovaks, South Slavs, and Germans. The armistice between the Allies and Austria-Hungary was signed on November 3, 1918, bringing an end to the empire's participation in the war.

The aftermath of World War I witnessed the complete disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, as Emperor Karl relinquished his authority and separate republics were proclaimed in German Austria and Hungary, bringing an end to the era of the Austrian Empire.

Victoria Austria China: Valuable Antiques or Worthless Trinkets?

You may want to see also

The Congress of Vienna

The Congress aimed to resize the main powers to balance and prevent future wars, while also suppressing revolutionary and liberal movements that threatened the conservative constitutional order. The negotiations resulted in France giving up all recent conquests, while the other three main powers—Britain, Prussia, and Austria—made significant territorial gains. Prussia acquired territory from smaller states, including Swedish Pomerania and most of the Kingdom of Saxony. Austria gained control of much of northern Italy, and Russia added the central and eastern parts of the Duchy of Warsaw.

The Congress's agreement was signed just nine days before Napoleon's final defeat at Waterloo on June 18, 1815. While some historians criticise the Congress for suppressing national and liberal movements, others praise it for bringing peace to Europe and preventing large-scale wars for almost a century. The Congress of Vienna was a pivotal event that reshaped the European political landscape and set the stage for the continent's future relations.

Mueller Austria: Worthy Brand or Overhyped?

You may want to see also

The Austrian-Hungarian Compromise

The compromise put an end to the 18-year-long military dictatorship and absolutist rule over Hungary by Emperor Franz Joseph, which had been instituted after the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. It partially re-established the former pre-1848 sovereignty and status of the Kingdom of Hungary, separate from the Austrian Empire. The territorial integrity of Hungary was restored, and its old historic constitution was reinstated. Hungary's legal and political status was returned, and the April Laws of the Hungarian revolutionary parliament were also restored, with the exception of laws based on the 9th and 10th points.

Under the Compromise, the lands of the House of Habsburg were reorganized as a real union between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, with a single monarch. This monarch reigned as Emperor of Austria in the Austrian half of the empire and as King of Hungary in the Kingdom of Hungary. The Cisleithanian (Austrian) and Transleithanian (Hungarian) states had separate constitutions, governments, parliaments, and prime ministers. However, they conducted unified diplomatic and defence policies, with common ministries of foreign affairs, defence, and finance.

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise was unpopular among ethnic Hungarian voters, who felt it betrayed the vital interests and achievements of the 1848-49 War of Independence. It caused deep and lasting cracks in Hungarian society, and the maintenance of the Compromise was largely due to the popularity of the pro-compromise ruling Liberal Party among ethnic minority voters in Hungary.

The dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary lasted until the end of World War I in 1918, when the empire was dissolved and separate nations were established.

Austrian Crystal: A Guide to Its Brilliance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Austrian Empire was established in 1804 by Francis II, the Holy Roman Emperor, in response to Napoleon's growing power and the threat he posed to the Holy Roman Empire.

The Austrian Empire survived until 1867 when it became the Austro-Hungarian Empire through the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, which joined the Kingdom of Hungary and the Empire of Austria.

The Austro-Prussian War of 1866 resulted in Austria's expulsion from the German Confederation. This defeat caused Emperor Franz Joseph to reorient his policy toward the east and consolidate his heterogeneous empire, leading to the Compromise of 1867.

Napoleon's expansionist efforts and military victories led to negotiations and peace treaties that resulted in the loss of some Habsburg territories. Napoleon's eventual defeat allowed Austria and its allies to reorganise borders more favourably at the Congress of Vienna in 1814/1815.