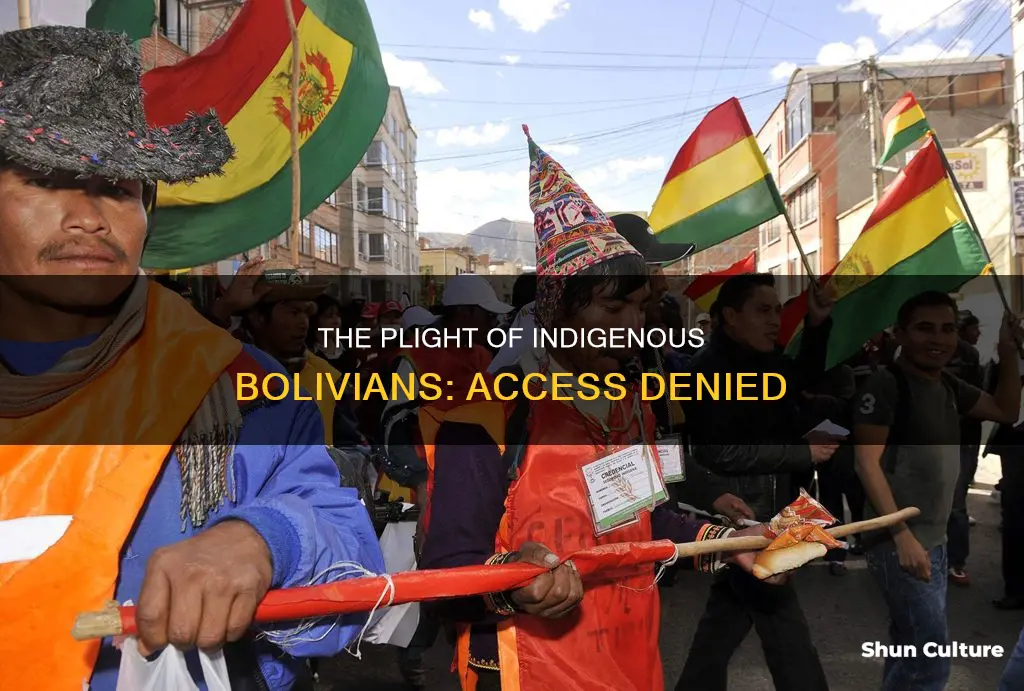

Indigenous people in Bolivia have historically faced many challenges and injustices. While they constitute anywhere from 20 to 60% of the country's population, they have been marginalised and underrepresented for many years. Despite some improvements in recent years, such as the election of Evo Morales, Bolivia's first Indigenous president, and the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous communities in Bolivia still face significant issues. These include environmental injustices, land rights disputes, and a lack of political representation and inclusion in decision-making processes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Representation in politics | Poor |

| Land rights | Insufficient |

| Political mobilisation | Increasing |

| Self-governance | In progress |

| Collective ownership | 23 million hectares |

| Population | 2.8 million (2012 census) |

What You'll Learn

Political representation

Indigenous people in Bolivia have historically lacked political representation, but this has improved in recent years, particularly under the leadership of Evo Morales, the country's first indigenous president.

Indigenous people in what is now Bolivia have been subject to pervasive racial discrimination and marginalization for centuries, dating back to Spanish colonialism. During colonial times, society was divided into hierarchical castes, with "brute Indians" at the bottom, excluded from political power and representation. This situation persisted even after Bolivia gained independence, with the indigenous population remaining severely marginalized.

The 1952 Bolivian National Revolution brought about some changes, as indigenous peoples were granted full citizenship. However, they were not formally recognized as indigenous by the state but were instead categorized as non-ethnic rural farmers or "campesinos". As a result, they continued to face intense poverty and a lack of access to the levers of power.

In the 1960s and 1970s, social movements such as the Katarista movement emerged, seeking to mobilize the indigenous community and pursue an indigenous political identity through mainstream politics. While the Katarista movement failed to create a national political party, it influenced various peasant unions and laid the groundwork for future political mobilization.

The late twentieth century saw a surge of political mobilization among indigenous communities in Bolivia. Reforms such as the 1993 Law of Constitutional Reform acknowledged indigenous rights in Bolivian culture and society. Additionally, the 1994 Law of Popular Participation decentralized political structures, granting more political autonomy to municipal and local governments. The 1996 Electoral Law further expanded indigenous political rights by transitioning to a hybrid proportional system, increasing the number of indigenous representatives in the national congress.

Despite these advancements, many reforms fell short, as subsequent governments continued to pass destructive environmental and anti-indigenous regulations, particularly related to the exploitation of natural resources. Environmental injustice became a polarizing issue, with indigenous communities protesting against government-backed privatization and eradication of natural resources, including coca leaf production and water systems.

The election of Evo Morales, Bolivia's first indigenous president, in 2005 marked a significant turning point in the political representation of indigenous people in Bolivia. Morales filled 14 of 16 cabinet posts with people of indigenous descent and his political party, the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS), became the dominant force in the country. This opened up opportunities for indigenous leaders to enter politics at various levels, from town mayors to members of the national legislature. Morales's movement was largely responsible for a massive increase in indigenous participation in the national political process.

Morales also led an effort to rewrite the nation's constitution, which was completed in 2009. This new constitution recognizes the plurinational and communitarian nature of the Bolivian state, granting equal standing to liberal citizenship and new forms of collective indigenous citizenship. It specifies distinct indigenous rights and forms of cultural, political, and juridical autonomy throughout its 411 articles.

However, even under Morales's leadership, challenges remained. Some indigenous communities criticized his administration for its focus on extraction-based economic policies, which they felt came at the expense of their rights and territorial autonomy. Additionally, Morales faced opposition from upwardly mobile city dwellers of indigenous descent, who sought greater economic opportunities and felt his administration was too focused on indigenous questions.

In 2019, Morales resigned amid accusations of fraud and defying constitutional term limits, sparking a period of political turmoil. The interim president, Jeanine Áñez, has been accused of having an anti-indigenous bias, and her cabinet appointments have not included any indigenous representatives. As a result, indigenous people in Bolivia once again face a lack of representation in the highest levels of government.

Bolivia's World Cup Appearances: A Comprehensive Overview

You may want to see also

Land rights

Indigenous peoples in Bolivia have consolidated their collective ownership of 23 million hectares of land, which is around 21% of the country's total land mass. These lands are known as Tierras Comunitarias de Origen (TCOs) or Native Community Lands. However, despite these legal protections, indigenous communities continue to face challenges and threats to their land rights.

One significant challenge relates to the country's extractive industries, which are strongly promoted by the government. Although landlocked, Bolivia is rich in natural resources and relies heavily on resource extraction for revenue and foreign exchange. The government's promotion of mining and other extractive activities has led to conflicts with indigenous communities, who seek to protect their territories and natural resources.

Another contentious issue is the proposed road across the Isiboro-Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS) in the Bolivian Amazon. This road would cut through a protected indigenous homeland and a national park, impacting the local indigenous communities and the environment. Despite protests and a march by indigenous residents, the government has not definitively abandoned the project, and the threat of construction remains.

Additionally, lowland indigenous groups in Bolivia, such as the Chiquitano, Guaraní, and Moxeño, face threats from cattle ranching and colonisation. Their lands are targeted for agricultural expansion and resource extraction, and they have had to mobilise and march to demand recognition of their land rights. While some victories have been achieved, these communities continue to face pressure and challenges to their territorial autonomy.

The election of Evo Morales, Bolivia's first indigenous president, raised hopes for greater land protections and territorial autonomy for indigenous communities. However, despite some positive steps, problems persist, and indigenous communities continue to struggle for full control over their ancestral lands.

Bolivia's Historic May 25 Revolution: A Country Transformed

You may want to see also

Environmental destruction

Indigenous peoples in Bolivia have historically lacked environmental protection and continue to face environmental injustices. They have suffered from the government's destructive environmental policies and the negative impacts of extractive industries, such as mining and oil exploration.

Environmental Injustices

Indigenous communities in Bolivia have long protested against government-backed privatisation and the eradication of natural resources and landscapes. For example, the 2000 Water War in Cochabamba saw residents, alongside urban workers, rural peasants, and students, protest against the privatisation of the city's water system. Similarly, the Gas Wars of 2003 saw a united front of coca farmers, unions, and citizens protest the sale of Bolivia's gas reserves to the United States.

Extractive Industries

Bolivia's reliance on natural resources for economic growth has resulted in conflicts with Indigenous communities, particularly regarding extractive industries such as mining. Despite President Evo Morales' stated commitment to environmental protection, the passing of a mining law in 2014 ultimately reduced Indigenous communities' ability to resist extractive activities on their territories.

Oil and Gas Exploration

Indigenous peoples in Bolivia also face challenges due to seismic work in search of new oil and gas reserves. These projects directly impact the people inhabiting the territory, often Indigenous communities and peasants.

Deforestation and Forest Fires

The traditional territory of several Indigenous groups in Bolivia, such as the neighbouring dry forests of the Gran Chaco, is under threat from unauthorised and invasive agriculture and forest fires. Environmentalists have denounced the government's relaxation of restrictions on forest clearing, which has resulted in fires affecting millions of hectares in eastern Bolivia.

Conservation Efforts

Indigenous peoples in Bolivia have consolidated their collective ownership of 23 million hectares, constituting 21% of the country's total land mass. These areas are known as Tierras Comunitarias de Origen (Community Lands of Origin) or TCOs, and they encompass communities such as the Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park and the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory.

In partnership with Bolivian government agencies, Indigenous communities, and non-governmental organisations, conservation projects aim to protect these natural areas by improving the management of national parks, contributing to conservation efforts, and promoting sustainable financing systems.

Bolivia's Political Spectrum: Communist or Not?

You may want to see also

Economic inequality

Indigenous people in Bolivia have historically faced economic inequality. While they constitute anywhere from 20 to 60% of Bolivia's population, they have been marginalised and lacked representation. In recent years, there has been progress towards addressing these inequalities, with the election of Evo Morales, Bolivia's first Indigenous president, in 2005. However, economic inequality persists, and Indigenous communities continue to face challenges in terms of land rights and the impact of extractive industries.

Historical Context

Indigenous people in Bolivia, or Native Bolivians, have predominantly Amerindian ancestry and belong to 36 recognised ethnic groups. They have faced a long history of marginalisation and lack of representation. The 1952 Bolivian National Revolution gave Indigenous peoples citizenship but fell short in providing political representation. It was not until the late 20th century that there was a surge of political and social mobilisation within Indigenous communities, with movements such as the Katarista movement seeking to pursue an Indigenous political identity.

Recent Developments

In 2005, Evo Morales became the first Indigenous president of Bolivia, marking a significant step towards addressing economic inequality. Morales attempted to establish a plurinational and postcolonial state, expanding the collective rights of Indigenous communities. The 2009 constitution recognised the presence of different communities in Bolivia and granted Indigenous peoples the right to self-governance and autonomy over their ancestral territories.

Persistent Inequalities

Despite these advancements, economic inequality persists for Indigenous people in Bolivia. Land rights remain a serious issue, with problems arising from the country's extractive industries, which are strongly promoted by the government. Bolivia is rich in natural resources and relies heavily on resource extraction for revenue and national development. The government's support for mining interests has reduced the ability of Indigenous communities to resist extractive activities in their territories.

Impact of Extractive Industries

The impact of extractive industries on Indigenous communities in Bolivia is evident in the proposed road construction across the Isiboro-Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS). This project has faced strong opposition from Indigenous activists, who argue that it will primarily serve the interests of coca leaf-growers who have settled in the area. Additionally, seismic work in search of new oil and gas reserves, as well as hydroelectric projects, directly impact Indigenous peoples and peasants inhabiting the territory.

While there have been significant advancements in addressing economic inequality for Indigenous people in Bolivia, particularly with the election of Evo Morales, persistent challenges remain. The conflict between the government's promotion of extractive industries and the land rights and autonomy of Indigenous communities highlights the ongoing economic inequality faced by Indigenous peoples in Bolivia.

Exploring Bolivia's Rich Avian Diversity: Species Count Revealed

You may want to see also

Social discrimination

Indigenous people in Bolivia have historically faced social discrimination and marginalization, but their mobilization and inclusion in the political process have led to some improvements.

Historical Context

Indigenous people in Bolivia, or Native Bolivians, have predominantly Amerindian ancestry and constitute a significant portion of the country's population. They have a long history in the region, inhabiting territories that are now part of Bolivia for thousands of years before the arrival of Spanish colonial powers in the early 16th century. Despite this deep-rooted presence, they have often been marginalized and exploited for labor in mines and plantations.

Political Underrepresentation

The 1952 Bolivian National Revolution, led by the Movimiento Nacional Revolucionario (MNR), brought about significant political changes, including land reforms and greater inclusion of Aymara and Quechua farmers. However, even after gaining citizenship, Indigenous communities continued to lack adequate political representation. It wasn't until the 1960s and 1970s that social movements like the Katarista movement emerged to advocate for Indigenous concerns and pursue an Indigenous political identity. Despite these efforts, the Katarista movement was unable to establish a national political party.

Social Protests and Mobilization

Indigenous communities in Bolivia have a history of social protests and mobilization to defend their rights and resist destructive environmental policies. One notable example is their participation in the Water War in 2000, where they joined forces with urban workers, rural peasants, and students to protest against the privatization of Cochabamba's water system. Their collective action successfully reversed the privatization plans.

Environmental Injustice

Environmental injustice has been a polarizing issue for Indigenous communities in Bolivia, who have actively protested against government-backed privatization and eradication of natural resources and landscapes. Coca leaf production, an important sector of the Bolivian economy and culture, has been a particular point of contention. The government's efforts to eradicate coca production, influenced by the U.S. war on drugs, sparked heavy protests from the Indigenous community, led by figures like Evo Morales.

Recent Developments

In recent years, there have been some notable improvements in the social and political inclusion of Indigenous people in Bolivia. The election of Evo Morales, the country's first Indigenous president, in 2005 marked a significant milestone. Morales worked to establish a plurinational and postcolonial state, expanding the collective rights of Indigenous communities. The 2009 constitution recognized the presence of different communities in Bolivia and granted Indigenous peoples the right to self-governance and autonomy over their ancestral territories.

However, despite these advancements, challenges remain. Many Indigenous communities claim that the process of receiving autonomy is inefficient and lengthy. Additionally, issues like land rights and the negative impact of extractive industries on their territories continue to be a concern.

Finding Someone in Cochabamba, Bolivia: A Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

According to the 2012 National Census, 41% of the Bolivian population over the age of 15 are of Indigenous origin. However, the National Institute of Statistics' (INE) 2017 projections indicate that this percentage is likely to have increased to 48%.

There are 36 recognised Indigenous peoples in Bolivia, including the Aymara and Quechua (the largest communities in the western Andes), as well as Chiquitano, Guaraní and Moxeño, who make up the most numerous communities in the lowlands.

One of the major challenges for Indigenous Peoples in Bolivia is seismic work in search of new oil and gas reserves, as well as hydroelectric projects. These projects directly impact the people inhabiting the territory, who are often Indigenous and peasants. Additionally, 15 out of the 36 Indigenous communities in Bolivia are at risk of extinction due to systematic neglect, social exclusion, and geographic isolation.

Historically, Indigenous Peoples in Bolivia suffered marginalization and a lack of representation. However, the late 20th century saw a surge of political and social mobilization in Indigenous communities. While the 1952 Bolivian National Revolution gave Indigenous Peoples citizenship, it still offered little political representation. It was in the 1960s and 1970s that social movements such as the Katarista movement began to include Indigenous concerns and pursue an Indigenous political identity. In 2005, Evo Morales was elected as the country's first Indigenous president, and Bolivia became the first plurinational state in South America.

While there is a significant Indigenous presence in each of Bolivia's organs of power, there has been no comprehensive evaluation of their role. Many of these representatives are decided by regional or village organizations, and they often end up being co-opted by the political system. Additionally, issues such as land rights and environmental protection remain contentious, with Indigenous communities protesting against government decisions that dispose of their natural resources and implement "development" plans and projects on their land without consultation.