The Bolivian Water Wars, also known as the Cochabamba Water Wars, were a series of protests that took place in Cochabamba, Bolivia's fourth-largest city, between December 1999 and April 2000. The protests were sparked by the privatisation of the city's municipal water supply company, SEMAPA, which led to drastic increases in water rates. The Bolivian government had been pressured into privatising SEMAPA by the World Bank, which had provided financial aid to Bolivia during its economic crisis in the 1980s. The privatisation of the water supply resulted in a wave of demonstrations and police violence as people from all walks of life united to fight against the increase in water prices, with tens of thousands of people taking part in the protests. The protests culminated in a national agreement to reverse the privatisation of the water supply and recognise access to water as a human right.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date | December 1999-April 2000 |

| Location | Cochabamba, Bolivia |

| Cause | Privatisation of the city's municipal water supply company SEMAPA |

| Protestors | Peasants, retired unionised factory workers, union members, pieceworkers, sweatshop employees, street vendors, students, coca-leaf farmers, residential children, middle-class professionals |

| Protest Actions | Demonstrations, barricades, general strike, referendum, takeover of central plaza |

| Government Actions | Martial law, curfew, detention of protest leaders, restriction of travel and political activity |

| Outcome | Privatisation reversed, protest leaders released, Law 2029 repealed |

What You'll Learn

The Bolivian government's decision to privatise the country's water supply

In the 1980s, Bolivia's economy was wrecked by hyperinflation, which reached an annual rate of 25,000% in 1985. This led to the country seeking financial aid from the World Bank, which required the privatisation of the country's railroads, airlines, telephone system, and oil industry. The World Bank also pushed for the privatisation of water.

In 1999, the Bolivian government, under President Hugo Banzer, decided to privatise the country's water supply. This was done through two major private concessions. The first was in La Paz/El Alto to Aguas del Illimani S.A. (AISA), a subsidiary of the French company Suez, in 1997. The second was in Cochabamba to Aguas del Tunari, a subsidiary of the multinationals Biwater and Bechtel, in 1999.

The decision to privatise the water supply in Cochabamba was particularly controversial. Cochabamba's waterworks had previously been owned by the state agency SEMAPA, which was inefficient, costly, and unable to meet the growing demand for water. The privatisation of the city's water supply was done through a 40-year concession to Aguas del Tunari, which was the sole bidder for the project. The consortium was guaranteed a minimum 15% annual return on its investment, which was to be adjusted annually to the United States' consumer price index.

The decision to privatise the water supply in Cochabamba led to a wave of protests and demonstrations, known as the Cochabamba Water War. The protests were sparked by a sharp increase in water rates imposed by Aguas del Tunari, which put access to water at risk for many poor people. The protests, which took place between December 1999 and April 2000, involved a broad alliance of farmers, factory workers, rural and urban water committees, neighbourhood organisations, students, and middle-class professionals. The protests were met with violence from the police and led to a state of emergency being declared in April 2000.

Bolivian School Uniforms: What Students Wear in Class

You may want to see also

The role of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) played a significant role in the events that led to the Bolivian Water Wars.

In the 1980s, Bolivia was facing economic instability, with hyperinflation reaching an annual rate of 25,000%. As a result, the country turned to the World Bank for financial aid, which came with stringent conditions. The World Bank pushed for the privatisation of several state-owned industries, including railroads, airlines, the telephone system, and the oil industry, and water.

The World Bank's involvement in Bolivia's water sector was driven by its belief that privatisation would improve efficiency and reduce waste. It advised against government subsidies to mitigate the increase in water tariffs, arguing that subsidies often benefited middle-class neighbourhoods and industries rather than the poor. The World Bank's "Major Cities Water and Sewerage Rehabilitation Project" included a condition to privatise the water utilities in La Paz and Cochabamba.

In Cochabamba, the state agency SEMAPA, which previously managed the city's waterworks, was put up for auction. This privatisation resulted in a 40-year concession being awarded to Aguas del Tunari, a multinational consortium. The Bolivian government, under President Hugo Banzer, agreed to the terms set by Aguas del Tunari, which included a guaranteed annual return of 15% on their investment.

The privatisation led to a significant increase in water rates, with prices skyrocketing to as much as $20 per month, which was unaffordable for many Bolivians, especially those earning meagre wages. This drastic hike in water rates sparked widespread protests and demonstrations, which became known as the Bolivian Water Wars.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) also played a role in the broader context of Bolivia's economic situation. The IMF, in conjunction with the World Bank, promoted economic policies that encouraged privatisation and market liberalisation. The IMF's role in Bolivia specifically included persuading the government to allow the privatisation of formerly state-owned industries, including the water company SEMAPA.

The IMF's stated mission is to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, and promote economic growth and poverty reduction. However, critics argue that its policies often fail to achieve these goals and can even exacerbate income inequality. In the case of Bolivia, the IMF's push for privatisation, coupled with the World Bank's influence, contributed to the tensions that erupted during the Bolivian Water Wars.

Bolivia's Response to Water Contamination Crisis

You may want to see also

The involvement of Bechtel and Aguas del Tunari

The Bolivian Water War, also known as the Cochabamba Water War, was a series of protests that took place in Cochabamba, Bolivia's fourth-largest city, between December 1999 and April 2000. The conflict was sparked by the privatisation of the city's municipal water supply company, SEMAPA, and the subsequent increase in water rates.

Aguas del Tunari was a consortium between the British firm International Waters (55%)—itself a subsidiary of the US construction giant Bechtel (which owned 50% of International Water)—and United Utilities (UK), as well as the engineering and construction firm Abengoa of Spain (25%) and four Bolivian companies, including Befesa/Edison, Constructora Petricevic, Sociedad Boliviana de Cemento (SOBOCE), Compania Boliviana de Ingenieria, and ICE Agua y Energia S.A.

In 1997, the World Bank informed Bolivia that it would make additional aid for water development conditional on the privatisation of the public water systems of its two largest urban centres, El Alto/La Paz and Cochabamba. In September 1999, in a secret process with just one bidder, Bolivia's government turned over Cochabamba's water supply to Aguas del Tunari, which was controlled by Bechtel.

Within a few weeks, Bechtel's company raised water rates by an average of more than 35%, sparking citywide protests that became known as the Bolivian Water War. In addition to the rate hike, many Bolivians were concerned that a new law, Law 2029, gave Aguas del Tunari a monopoly over all water resources, including water used for irrigation by peasant farmers and community-based resources that had previously been independent of regulation.

In April 2000, following a wave of protests, the Bolivian government rescinded its contract with Aguas del Tunari and the company was forced to leave the country. In November of that year, Aguas del Tunari initiated a $50 million legal case against Bolivia before a closed-door trade court operated by the World Bank, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). For the next four years, Bechtel and Abengoa were met with protests, damaging press, and public demands from five continents that they drop the case. Finally, in January 2006, Bechtel and Abengoa representatives travelled to Bolivia and agreed to abandon the ICSID case for a token payment of 2 bolivianos (30 cents).

Renewing Your Bolivian Passport: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

The subsequent increase in water prices

The Bolivian Water War, also known as the Cochabamba Water War, was a series of protests that took place in Cochabamba, Bolivia's fourth-largest city, between December 1999 and April 2000. The conflict was sparked by the privatisation of the city's municipal water supply company, SEMAPA, and the subsequent increase in water prices.

The privatisation of SEMAPA resulted in a significant increase in water prices for the residents of Cochabamba. Aguas del Tunari, the consortium that took over the city's water supply, raised water rates by an average of 35%, with some customers experiencing increases of upwards of 50%. This meant that many residents were paying around $20 a month for their water supply, a significant amount considering that many of them earned only about $100 per month.

The increase in water prices was due to several factors. Firstly, Aguas del Tunari had agreed to pay off the $30 million debt accumulated by SEMAPA and finance an expansion and maintenance program for the existing water system. These costs were passed on to consumers in the form of higher water rates. Secondly, Aguas del Tunari had been granted a concession that guaranteed them a minimum 15% annual return on their investment, which was adjusted to the United States' consumer price index. This meant that the company had a strong incentive to maximise profits by increasing water rates. Finally, the Bolivian government's decision to privatise the water supply was influenced by the World Bank, which had advised the country to sell off its assets, including water, in order to receive ongoing state loans. The World Bank specifically discouraged the Bolivian government from providing subsidies to ameliorate the increase in water tariffs.

The increase in water prices had a significant impact on the residents of Cochabamba, particularly those from lower-income backgrounds. Many people struggled to afford the higher water rates, and some were forced to cut back on other necessities to pay their water bills. This led to widespread anger and resentment towards Aguas del Tunari and the Bolivian government, which eventually erupted into the Bolivian Water War.

The protests during the Bolivian Water War were characterised by widespread participation from various segments of society, including peasant irrigators, retired factory workers, union members, students, and middle-class professionals. The demonstrations were met with violence from the police and military, resulting in several injuries and deaths. The protests eventually led to the reversal of the privatisation of the water supply and a return to pre-2000 water prices. However, the aftermath of the conflict also highlighted the ongoing challenges of providing adequate water infrastructure and services in Bolivia.

Bolivia Visitor Visa: Application and Requirements Guide

You may want to see also

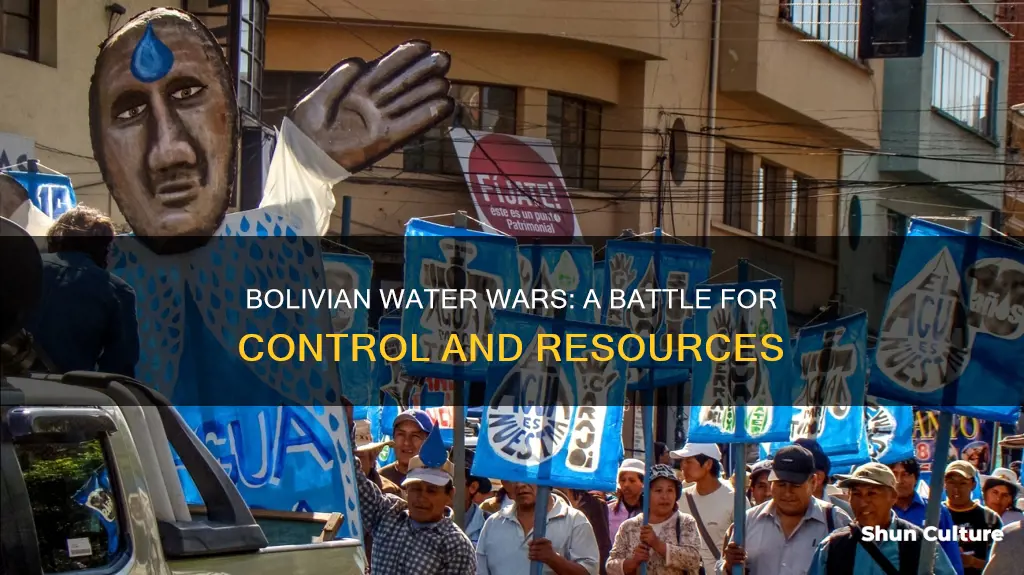

The public uprising and protests

The Bolivian Water War, also known as the Cochabamba Water War, was a series of protests that took place in Cochabamba, Bolivia's fourth-largest city, between December 1999 and April 2000. The protests were sparked by the privatisation of the city's municipal water supply company, SEMAPA, and the subsequent increase in water rates.

The protests began in early January 2000 and were led by outspoken leaders such as Oscar Olivera, a long-time union activist. The demonstrators halted Cochabamba's economy by holding a general strike that shut down the city for four days. Despite the government agreeing to roll back water rates, the protests continued, with thousands of people marching in February 2000. The demonstrations turned violent, with clashes between protesters and law enforcement resulting in injuries and arrests.

In April 2000, the protests escalated further as demonstrators once again took over Cochabamba's central plaza. Leaders of the Coordinadora, including Óscar Olivera, were arrested when they went to meet with the governor. This sparked further outrage, and the demonstrations spread to other areas of Bolivia, including La Paz, Oruro, and Potosí, as well as rural areas. The protesters expanded their demands, calling on the government to address unemployment and other economic issues. They blocked major highways and inspired officers in La Paz police units to refuse to leave their barracks until a wage dispute was settled.

Fearing a repeat of past uprisings, President Hugo Banzer declared a "state of siege" on 8 April 2000, suspending some constitutional guarantees and restricting civil liberties. This led to further clashes between demonstrators and law enforcement, resulting in internal exile, injuries, and deaths. On 9 April 2000, soldiers and protesters clashed near the city of Achacachi, resulting in the deaths of two people, including a teenage boy, Víctor Hugo Daza, who was shot in the face. This incident further fuelled the protests, and the demonstrators demanded justice for the deaths caused by the military.

The Bolivian Water War gained international attention and inspired similar protests against water privatisation and globalisation. The protests ultimately led to the reversal of privatisation, with the national government reaching an agreement with the Coordinadora to cancel the contract with Aguas del Tunari and return water control to the public sector.

Bolivia: A Country of Diversity and Culture

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Bolivian Water War, also known as the Cochabamba Water War, was a series of protests that took place in Cochabamba, Bolivia's fourth-largest city, between December 1999 and April 2000.

The Bolivian Water War was caused by the privatisation of the city's municipal water supply company, SEMAPA, which led to a significant increase in water rates.

SEMAPA was privatised by the Bolivian government, led by President Hugo Banzer, and sold to Aguas del Tunari, a consortium between several international companies, including Bechtel and United Utilities.

The World Bank had pressured the Bolivian government to privatise water as a condition for retaining ongoing state loans. They also provided assistance in preparing the concession contract for Cochabamba in 1997.

The outcome of the Bolivian Water War was that the privatisation of SEMAPA was reversed, and the company was returned to public control. The protests also inspired a worldwide anti-globalisation movement and influenced other water-justice struggles.