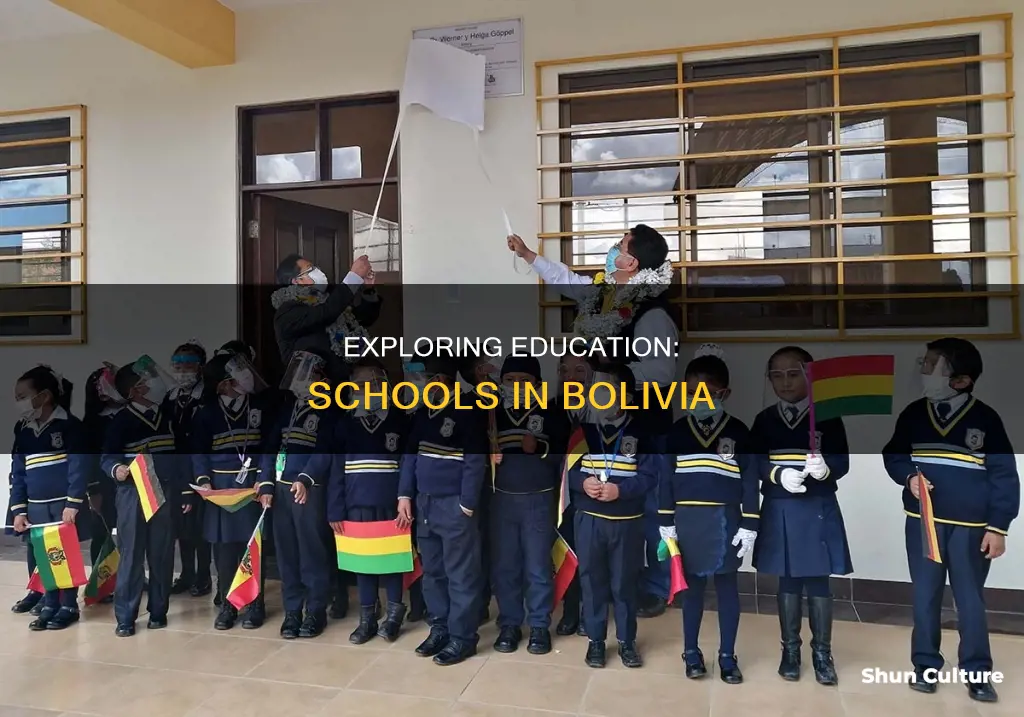

Bolivia's education system has a long history of inequality, with a divide between rural and urban areas. While the country has made efforts to improve access to education, issues such as high dropout rates and a lack of resources persist. The Bolivian government allocates a significant portion of its budget to education, but the system faces financial challenges, particularly in rural areas. The language of instruction is primarily Spanish, which has contributed to high dropout rates among rural students who speak other dialects. Bolivia's schools are also affected by teacher strikes, and the public system is criticised for its lack of organisation and quality. Despite these challenges, the country has made progress, with improvements in adult literacy rates and primary school enrolment over the years.

What You'll Learn

The school year and terms

The school year in Bolivia typically runs from February to November, with summer vacation taking place in December and January, the two hottest months of the year. This schedule is followed by most schools in the country, with a few private schools observing the US September-to-June school year.

The school week in Bolivia is also a little different from what many are used to. Elementary and high school students attend school either in the morning or in the afternoon, with each school day shift lasting only four hours. This means that students may also attend school on Saturdays. The short school day can pose challenges for working parents, who need to arrange childcare for the remainder of the day.

The Bolivian school system is divided into several stages. The first stage is a five-year primary cycle (1st to 5th grade), followed by three years of intermediate school (6th to 8th grade), and then four years of high school. The first two years of high school follow a unified curriculum, while the last two years allow students to choose between a degree in humanities or a technical field.

After completing high school, students can pursue higher education at universities or other institutes. The University of Bolivia, a consortium of eight public universities and one private university, is the main provider of post-secondary education in the country. However, there are also many private universities and institutes, some of which have agreements with overseas institutions, offering a range of educational opportunities for Bolivian students.

Winter in Bolivia: A Season of Adventure

You may want to see also

The impact of location

In rural areas, only about 40% of children attend school beyond the third grade, and they often face language barriers if their first language is not Spanish, the language of instruction in Bolivian schools. On average, children in rural areas receive 4.2 years of education, compared to 9.4 years for children in urban areas. This disparity is partly due to the fact that many rural children work to contribute to their family income, and also face challenges such as a lack of access to transportation and meals provided by schools.

The quality of schools also varies between rural and urban areas. Public schools in urban areas may be better maintained, furnished, and supplied than those in rural areas, which often rely on support from non-profit institutions. As a result, students in urban public schools may have higher learning levels than their rural counterparts.

The Bolivian government has made efforts to address these disparities, with 23% of its annual budget devoted to educational expenditures, a higher percentage than most other South American countries. However, the impact of location continues to play a significant role in the quality of education in Bolivia, with urban centres generally outpacing rural areas in terms of access to education and student outcomes.

Electricity Access in Rural Bolivia: How Many Covered?

You may want to see also

School meals and transport

Most schools in Bolivia do not provide meals for students. However, the success of a school meal programme in La Paz, which serves healthy breakfast and lunch to students, has led to the formulation of a new law by the Bolivian government. This law emphasizes the nutritional value of food from local produce and bans packaged and transgenic food in schools. The programme, which is part of the Complementary School Food Unit (ACE), provides meals to school-going children between the ages of 5 and 15. The diet is typically composed of quinoa grains and high-protein amaranth, which is native to South America's Andean region. The programme has not only improved the health of the children but has also contributed to the growth of the local food industry.

Transport in Bolivia is mostly by road, although the country's unique geography means aviation is also important. Bolivia's first light rail network is under construction in Cochabamba, and the country is also home to Mi Teleférico, the world's first urban transit network to use cable cars as the primary mode of transportation. This system services the twin cities of El Alto and La Paz.

Bolivia's extensive bus network is the most common way to travel within the country. Longer journeys are usually serviced by large double-decker buses called "Flotas", which are newer and more comfortable than city buses. These buses hold up to 80 passengers and are equipped with reclining seats. Passengers can choose from different seat types, ranging from the cheapest option, "Semi-Cama", to the most expensive, "Cama Premium". No meals are provided on Bolivian bus services, but passengers can bring their own food and drinks on board. Local vendors also sell hot meals to passengers when the bus makes a stop.

Bolivia also has a network of railways, although they play a relatively small part in the country's transport system. There are two separate networks: the Eastern network, which runs from Santa Cruz to the Brazilian border at Quijarro and the Argentine border at Yacuiba, and the Western network, which runs from Oruro to the Argentine border at Villazón, via Uyuni and Tupiza. The scenery on the Western network route is breathtaking, making it a great alternative to the bumpy bus ride between La Paz and Uyuni.

Exploring Bolivia During Easter: A Good Time?

You may want to see also

Teachers' strikes

Teachers in Bolivia have a history of industrial action, including partial strikes and daily marches, to advocate for their rights and improve their working conditions. One of the primary issues that have led to teachers' strikes in Bolivia is the accumulation of unpaid hours, referred to as the "historic deficit." Teachers often have to rely on impoverished working-class parents for payment and often work without insurance, pension payments, or other benefits. This issue of unpaid labour has been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, during which teachers provided remote lessons in many cases without receiving any compensation.

In addition to demanding better pay and working conditions, teachers in Bolivia have also advocated for improvements in the education system as a whole. They have called for increased educational funding and changes to the national curriculum. Teachers' unions, such as the Confederation of Urban Education Workers of Bolivia (CTEUB), have played a crucial role in organising these strikes and protests. However, the government has often been unwilling to concede to the demands of the teachers, leading to prolonged strikes and tensions between the two parties.

The teachers' strikes in Bolivia reflect a broader global trend of educators taking industrial action to address issues such as understaffing, low pay, and increased workloads. By standing together and advocating for their rights, Bolivian teachers are demanding that the government prioritise education and the wellbeing of its students and teachers.

Child Labour in Bolivia: Ethical Dilemma Explored

You may want to see also

Curriculum and subjects

The curriculum and subjects taught in Bolivian schools have undergone several changes since the 1950s.

In 1956, the Bolivian government established a six-year primary cycle, followed by four years of intermediate schooling and two years of secondary school, culminating in a baccalaureate degree. However, this curriculum was revised in 1969 and 1973, introducing a five-year primary cycle for students aged seven to fourteen, followed by three years of intermediate school and four years of secondary education. During the first two years of secondary education, students followed an integrated program, while the final two years allowed for specialisation in the humanities or various technical fields. All courses led to the baccalaureate degree, which was necessary for university entrance.

The University of Bolivia, a consortium of eight public universities and one private university (Bolivian Catholic University), was the only post-secondary institution awarding degrees in the late 1980s. However, there were also unauthorised private institutions operating, as well as schools offering technical training in fields like fine arts, commercial arts, and teacher training.

In 1994, Bolivia implemented a comprehensive education reform to address local needs, improve teacher training, curricula, and intercultural bilingual education, and change the school grade system. This reform aimed to decentralise educational funding and address the divide between rural and urban areas in terms of literacy and educational opportunities. Despite resistance from teachers' unions, this reform brought about significant changes.

Today, the Bolivian education system still includes a five-year primary cycle, followed by three years of intermediate school and four years of secondary education. Students in the final two years of secondary school can choose to specialise in the humanities or technical fields, and a baccalaureate degree is awarded upon graduation, enabling them to take the university entrance exam.

Neymar's Return: Will He Face Bolivia?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The school year in Bolivia typically runs from February to November, with summer vacation in December and January. There is a two-week winter vacation in June or July. Students attend school from Monday to Friday, with classes lasting from 8 am to 1 pm. The school day is short, with each student attending either in the morning or afternoon, so working parents must arrange childcare for the remainder of the day.

The quality of education in Bolivia varies greatly between urban and rural areas. Rural illiteracy levels remain high, and only around 40% of rural children attend school beyond the third grade. In urban areas, approximately 87% of children attend primary school, but only about 35% make it to high school. Overall, Bolivia's public education system is lacking in terms of organisation and quality, with schools often poorly maintained and under-resourced. However, improvements are ongoing, and many public schools are now supported by non-profit institutions, which are usually in excellent condition.

The Bolivian curriculum is standardised across all public and private schools by the Ministry of Education. Primary education is currently a five-year mandatory program followed by three years of intermediate school. In the first two years of high school, all students follow the same curriculum, which includes mandatory subjects such as math, physics, natural science, literature, art, religion, computing, chemistry, social studies, philosophy, languages, physical education, and music. In the final two years of high school, students can choose to specialise in the humanities or a technical field.