The Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire were a series of uprisings that took place from March 1848 to November 1849. The revolution in Vienna, which began on 13 March 1848, led to the overthrow of State Chancellor Metternich, freedom of the press, and the proclamation of a constitution. The revolution was driven by nationalist sentiments, as well as liberal and socialist ideologies that resisted the Empire's longstanding conservatism. The Austrian revolutions were influenced by the broader context of the Industrial Revolution, social unrest, and the rise of nationalism across Europe.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date | 1848-1849 |

| Part of | European-wide revolution |

| Causes | Disgust with conservative domestic policies, urge for more freedom and participation in government, rising nationalism, social problems brought on by the Industrial Revolution, increasing hunger caused by harvest failures |

| Notable figures | Prince Metternich, Lajos/Louis Kossuth, Emperor Ferdinand, Franz Joseph, Field Marshal Radetzky, Josip Jelačić, Archduke Johann, Czar Nicholas I |

| Outcome | Suppression of the revolution by the Habsburgs, execution of radical leaders, abdication of Emperor Ferdinand, accession of Franz Joseph |

What You'll Learn

The Industrial Revolution's impact

The Industrial Revolution, which spread to Austria in the 1840s, was a significant factor leading up to the 1848 Revolution. It hurt small businesses and brought about poor working conditions, making ordinary citizens, particularly the middle and lower classes, more receptive to revolutionary thought. The Industrial Revolution also brought about an intensification of social problems caused by economic cycles of boom and bust and an increasingly mobile population.

The onset of the Industrial Revolution in Austria was characterised by the development of infrastructure, including railroads and water transport. The first railway on the European continent was a horse-drawn line between Linz and Budweis, connecting the Danube and the Moldau rivers. By 1836, a steam railway was being built north of Vienna, and by 1848, the Austrian Empire had over 1,000 miles of track. Steam navigation on the Danube also began in 1830 and expanded quickly.

The Industrial Revolution also contributed to the rise of economic liberalism in Austria. After the death of Emperor Francis in 1835, restrictions on new enterprises were lifted, and by the 1840s, Austrian production of pig iron, coal, cotton textiles, woollens, and foodstuffs was growing at a faster rate than that of the Zollverein, the German customs union.

The social impact of the Industrial Revolution became starkly apparent in 1848 when the final abolition of serfdom was encouraged by some of the landowning nobility, who relied more and more on wage labour to work their estates. The Industrial Revolution's impact on small businesses and working conditions, as well as the social changes it brought about, helped create the conditions for the 1848 Revolution in Austria.

Exploring Austria: Planning Your Visit and Visa Requirements

You may want to see also

The role of nationalism

The Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire were a series of uprisings with a strong nationalist character. The ethnically diverse Austrian Empire was ruled from Vienna and included Germans, Hungarians, Poles, Bohemians (Czechs), Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Slovenes, Slovaks, Romanians, Croats, Italians, and Serbs. Each ethnic group within the Austrian Empire yearned to express its individual "volksgeist" and gain independence.

In March 1848, a radical Hungarian Magyar group led by Louis Kossuth began a vocal independence movement. Kossuth's fiery speeches were soon printed in Vienna, where they started a sensation and an uprising. This was followed by similar movements by Austrian Czechs and several Austrian-controlled Italian states.

The Slavs also played a significant role in the nationalist aspect of the revolution. In June 1848, a group of Slavic nationalists held a Pan-Slavism conference in Prague to prevent Bohemia from being swallowed by Germany. The conference turned violent, and Emperor Ferdinand of Austria crushed the Prague insurrection using his army.

The Hungarians' quest for independence was another prominent feature of the nationalist landscape during the 1848 revolutions. Under the leadership of Lajos (or Louis) Kossuth, the Hungarian Diet demanded sweeping reforms, including civil liberties and greater autonomy from the Austrian Empire. The Hungarian legislators created a new constitution, known as the March or April Laws, which provided for a popularly elected lower house of deputies, freedom of the press, peasant emancipation, and equality before the law. However, the new Hungarian government faced resistance from minority nationalities, such as the Serbo-Croatians, who did not speak the Magyar language and felt marginalized by the new regime.

The nationalist fervor during the 1848 revolutions in the Austrian Empire was not limited to the subject nationalities but also extended to the Germans themselves. German nationalists advocated for the unification of German states, including the German-speaking provinces of the Austrian Empire. However, they faced a dilemma regarding the inclusion of Austria, as it would mean incorporating non-German territories, which went against their desire for a united German state.

In summary, the role of nationalism in the 1848 revolutions in the Austrian Empire was significant. The various ethnic groups within the empire sought to express their unique identities and gain independence. This led to uprisings, the creation of new constitutions, and violent clashes. The nationalist movements ultimately contributed to the fall of Metternich, the relaxation of censorship, and the abolition of feudal obligations on peasants.

Austria's Survival: World War II's Impact and Legacy

You may want to see also

Social and political conflict

The Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire were a set of revolts that took place from March 1848 to November 1849. The social and political conflict of this period was driven by several factors, including nationalist sentiments, resistance to conservative policies, rising hunger due to harvest failures, and the social problems brought on by the Industrial Revolution.

Nationalist Sentiments

The Austrian Empire, ruled from Vienna, was ethnically diverse, including Germans, Hungarians, Poles, Bohemians (Czechs), Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Slovenes, Slovaks, Romanians, Croats, Italians, and Serbs. Each ethnic group increasingly yearned to express its individual national identity and gain independence. In March 1848, a radical Hungarian Magyar group led by Louis Kossuth began a vocal independence movement, and Austrian Czechs and several Italian states under Austrian control soon followed suit.

Resistance to Conservative Policies

The Austrian Empire, led by Prince Metternich, was the paragon of reactionary politics. Metternich worked to hold the empire together and opposed assimilation, further restricting freedom of the press, limiting university activities, and banning fraternities. Despite this lack of freedom, there was a flourishing liberal German culture among students and educated individuals who published pamphlets and newspapers advocating for basic liberal reforms. They were opposed to popular sovereignty and the universal franchise but advocated for relaxed censorship, freedom of religion, economic freedoms, and a more competent administration.

Social Problems and Rising Hunger

The Industrial Revolution, which spread to Austria in the 1840s, hurt small businesses and brought about poor working conditions, making the middle and lower classes more receptive to revolutionary thought. Additionally, potato blight originating in North America led to harvest failures and food shortages throughout Europe, causing hunger and soaring food prices.

Conflict Between Social Classes

Educational opportunities in 1840s Austria outstripped employment opportunities, leading to a radicalized, impoverished intelligentsia. The lack of a well-developed middle class in Austria meant that the revolution, led by intellectuals and students, struggled to gain widespread support. The illiterate and rural peasants, who primarily made up the army, had no notion of nationalism and remained loyal to the Habsburgs, helping to suppress the revolution.

The End of Austria-Hungary: A Historical Split

You may want to see also

The influence of the French February Revolution

The French February Revolution of 1848, also known as the French Revolution of 1848, had a significant influence on the Austrian Empire, setting off a series of revolutionary movements across the empire. Here is a detailed account of the influence of the French February Revolution on Austria:

The Spark of Revolution:

The revolution in Paris, which began in February 1848, inspired similar uprisings in other European cities, including Vienna. The news of the Paris uprising reached Vienna in March 1848, sparking demonstrations by students and members of liberal clubs demanding basic freedoms and a more liberal regime.

The Rise of Nationalism:

While the initial demonstrations in Vienna were driven by social and democratic-liberal ideals, the national aspect of the revolution soon took precedence, particularly in Hungary. Emperor Joseph II's attempts to centralize power in Vienna and impose German as the common administrative language had previously sparked resistance among the empire's non-German populations. The revolution in Paris emboldened the Hungarian Diet, led by Lajos Kossuth, to demand sweeping reforms, including civil liberties and greater autonomy from the Habsburg monarchy.

The Spread of Liberal Ideas:

The revolution in Paris fuelled the spread of liberal ideas and a desire for greater participation in government across the Austrian Empire. The demonstrators in Vienna called for a constitution, and the Habsburgs, seeking to appease the crowds, dismissed Prince Metternich, the conservative State Chancellor, and promised constitutional reforms. This period witnessed a power struggle between revolutionary and counter-revolutionary forces in Vienna, with the Habsburgs fleeing the city temporarily before regaining control and executing several radical leaders in October 1848.

Nationalist Movements:

Military Conflicts:

The revolutionary fervour led to military conflicts within the empire, pitting the Habsburg forces against various nationalist groups. Josip Jelačić, the governor of Croatia, known for his loyalty to the monarchy, rejected the authority of the Hungarian government and clashed with Hungarian forces. Additionally, the Habsburgs faced military challenges in Italy, where the kingdom of Sardinia declared war on the emperor, marching into Austrian territories. These conflicts resulted in victories for the Habsburgs, who regained control of Milan and Venice and suppressed the Hungarian revolution with the help of Russian forces.

The Impact on Social and Political Structures:

In conclusion, the French February Revolution of 1848 had a profound and lasting impact on the Austrian Empire, igniting revolutionary movements, intensifying nationalist sentiments, and reshaping social and political structures. The influence of the revolution extended beyond Vienna, reaching various regions of the empire and contributing to a period of significant upheaval and change.

Austria's Germanic Roots: A Cultural Identity Crisis?

You may want to see also

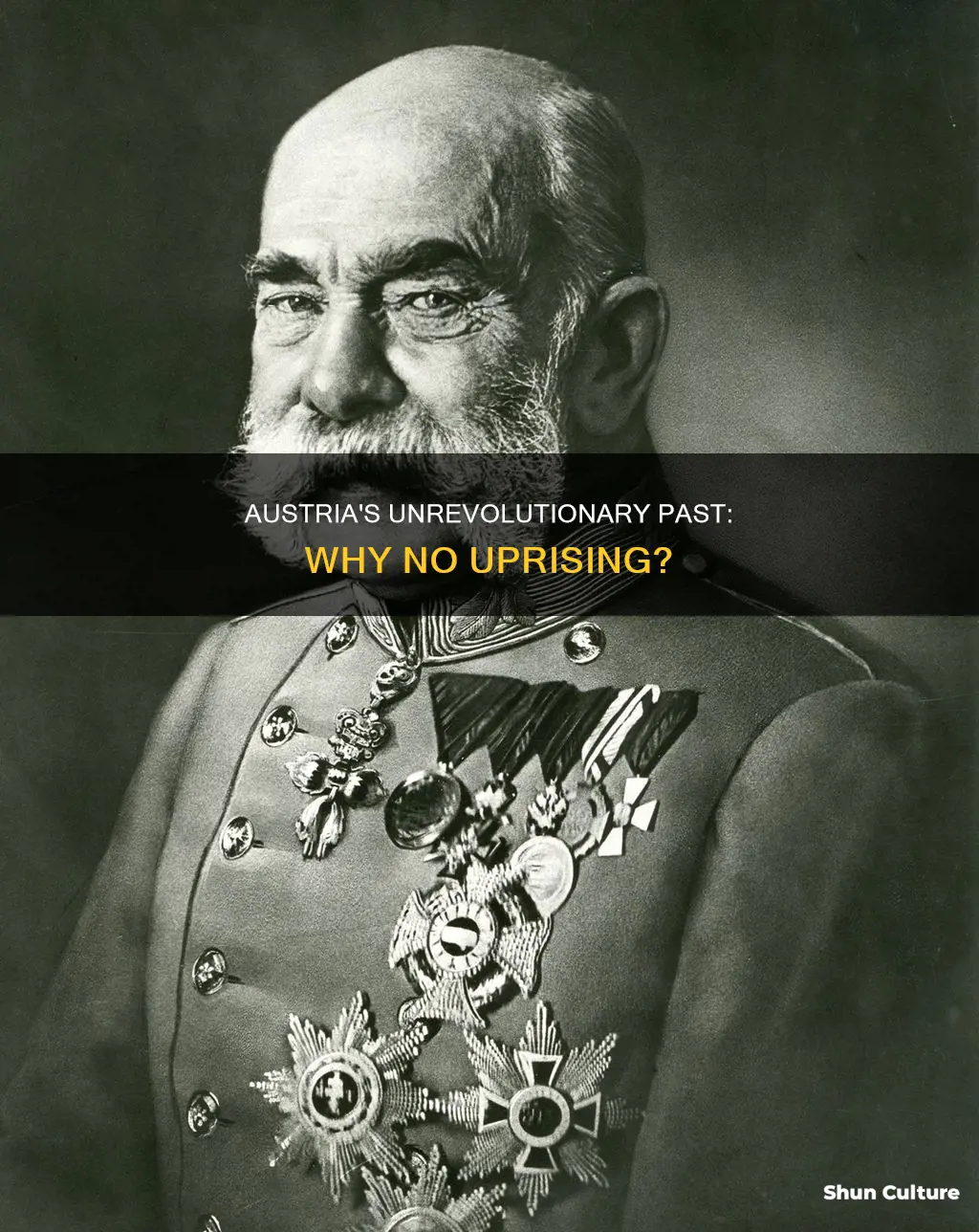

The Habsburg monarchy's response

The revolutions were sparked by a number of factors, including a general disgust with conservative domestic policies, a desire for more freedoms and greater participation in government, rising nationalism, social problems brought on by the Industrial Revolution, and increasing hunger caused by harvest failures in the mid-1840s. The Austrian Empire, ruled from Vienna, included Germans, Hungarians, Poles, Bohemians (Czechs), Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Slovenes, Slovaks, Romanians, Croats, Italians, and Serbs, all of whom attempted to achieve autonomy, independence, or hegemony over other nationalities during the revolution.

The first response of the Habsburg monarchy to the revolution was to flee. On 13 March 1848, revolution broke out in Vienna, leading to the overthrow of State Chancellor Metternich, freedom of the press, and the proclamation of a constitution. Metternich, the symbol of repression, resigned and fled to London. Ferdinand I of Austria then appointed new, nominally liberal ministers. However, the established order collapsed rapidly due to the weakness of the Austrian armies.

The Habsburgs and their government returned to Vienna in August 1848 when it appeared that more conservative elements were asserting control. The emperor issued a constitution in April providing for an elected legislature, but when the legislature met in June, it rejected this constitution in favour of one that was more democratic. As the legislature debated, the Habsburgs and their advisers regrouped and, on 31 October, the army retook Vienna and executed several of the city's radical leaders. The legislature was dismissed and the emperor issued a new constitution.

The Habsburg monarchy also responded to the revolutions in Hungary and Italy. In Hungary, the Diet demanded sweeping reforms, including civil liberties and greater autonomy for the Hungarian government. Under pressure from liberal elements in Vienna, the emperor acceded to these demands, and the Hungarians immediately undertook the creation of a new constitution, the March or April Laws. However, the new Hungarian government encountered resistance from minority nationalities, and the Habsburgs ultimately demanded greater concessions from the Hungarians. In September 1848, military action against Hungary by Josip, Graf (Count) Jelačić, prompted the Hungarian government to turn power over to Lajos Kossuth and the Committee of National Defence, which took measures to defend the country. What followed was open warfare between regular Habsburg forces and the Hungarians. The Hungarian army eventually surrendered in August 1849, and the land was put firmly under Austrian rule.

In Italy, the banner of revolt was raised in many places, especially Milan and Venice. In late March 1848, the Kingdom of Sardinia, the only Italian state with a native monarch, declared war on the emperor and marched into his lands. The Habsburg government was initially willing to make concessions, but this was overruled by their military commander in Italy, Field Marshal Radetzky, who reimposed Habsburg rule in Milan and Venice. In March 1849, Radetzky defeated the Sardinians once again when they invaded Austria's Italian possessions.

Austrian Economics vs Classical Economics: What's the Difference?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The revolution in Austria took place from March 1848 to November 1849.

The revolution was caused by a mix of social, political, and economic factors. Socially, there was a rise in nationalism among the various ethnic groups in Austria, who sought to express their individual culture and gain independence. Politically, there was opposition to the conservative policies of State Chancellor Metternich, including restrictions on freedom of the press and university activities. Economically, the Industrial Revolution had hurt small businesses and brought about poor working conditions, making people more receptive to revolutionary thought.

The revolution began in March 1848 with the overthrow of State Chancellor Metternich and the proclamation of freedom of the press and a constitution. However, the established order collapsed due to the weakness of the Austrian armies, and there were periods of revolution and counterrevolution. Liberal governments were short-lived, and by November 1848, Emperor Ferdinand had regained power in Vienna and appointed conservative ministers.

The revolution ultimately failed to create a working constitution for Austria, but it did result in the full emancipation of the peasantry, abolishing all feudal obligations. It also led to the rise of nationalism and the desire for self-rule among the different ethnic groups within the Austrian Empire.

The revolution in Austria was part of a wider wave of revolutions across Europe in 1848, including in Paris, Milan, Venice, and other major cities. While the Austrian revolution was driven by nationalism and a desire for political reform, other revolutions, such as in Paris, had a more social and democratic character.