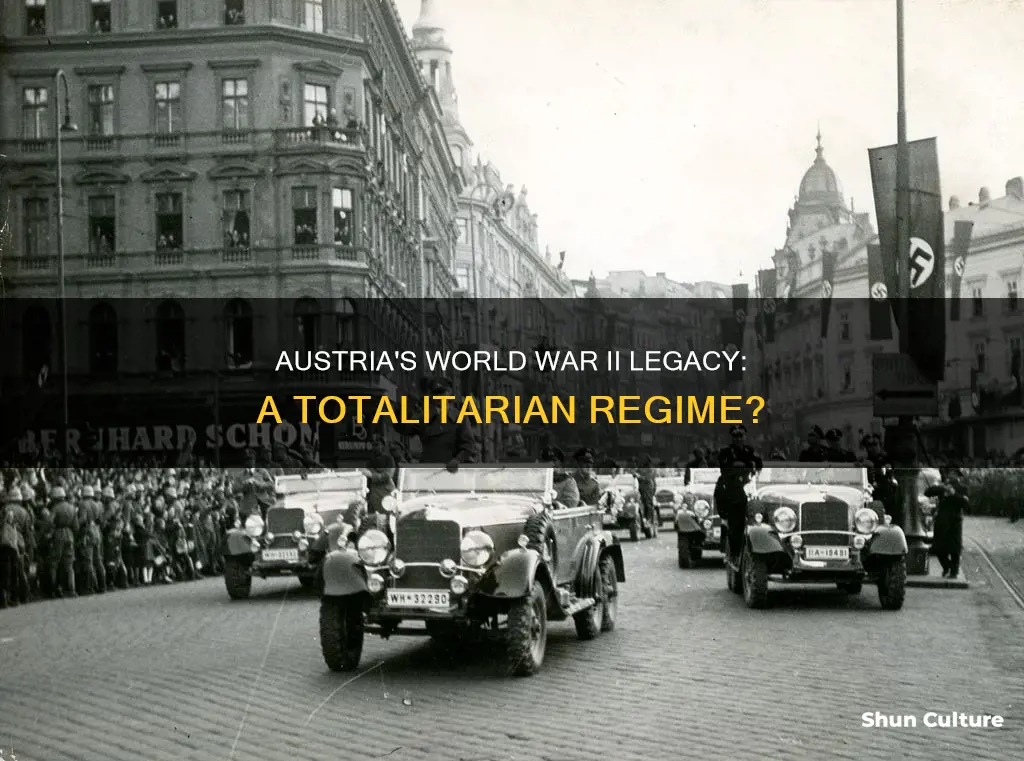

Austria was part of Nazi Germany from 13 March 1938 until 27 April 1945, when Allied-occupied Austria declared independence. During this time, the country was under the rule of a fascist, authoritarian government, with the majority of the population enthusiastically supporting the Nazi regime.

In the years leading up to World War II, Austria underwent significant political upheaval, with violent clashes between left-wing and right-wing groups. The Christian Social Party, which had strong ties to the Roman Catholic Church, dominated the government and pursued an anti-Anschluss agenda. However, the country was in a state of flux, with economic troubles and violent civil strife.

In 1933, Engelbert Dollfuss, the Chancellor of Austria, suspended parliament and established an authoritarian government, banning the Communist Party and the Social Democratic paramilitary organisation. This set the stage for a dictatorial regime, with Dollfuss creating the Fatherland Front, a fascist and conservative movement.

Following Dollfuss' assassination by Austrian Nazis in 1934, his successor, Kurt Schuschnigg, maintained the ban on Nazi activities and the authoritarian rule. However, this period also saw a growing influence of Nazi sympathisers within the government.

With the Anschluss in 1938, Austria became an integral part of the Third Reich, and a significant portion of the population joined the Nazi Party. Austrians fought loyally as soldiers and participated in the Nazi administration, including senior leadership roles.

While the extent of totalitarian rule in Austria during World War II is complex and debated, the country was undoubtedly a key component of the Nazi war machine, and many Austrians actively participated in and supported the Nazi regime.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Part of Nazi Germany | Yes, from 13 March 1938 (Anschluss) until 27 April 1945 |

| Support for Nazi Germany | Most Austrians supported the Anschluss, and 950,000 Austrians fought for the Nazi German armed forces during World War II |

| Austrian resistance | A small minority of the Austrian population actively participated in the resistance against Nazism |

| Austrian Nazi Party membership | 700,000 people (10% of the population) |

| Austrian Nazi atrocities | Austrians served loyally as soldiers and were responsible for Nazi atrocities on the Eastern Front |

What You'll Learn

Nazi Germany's annexation of Austria

The annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, known as the Anschluss, was the first act of territorial aggression by the Nazi regime. It took place on 12 March 1938, when German troops marched into Austria to annex the German-speaking nation for the Third Reich. The idea of a union between Austria and Germany, resulting in a "Greater Germany", had been proposed after the unification of Germany in 1871 excluded Austria. This proposal gained support after the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, and the subsequent economic crisis that hit Austria.

In the 1920s, the idea of a union was supported by many Austrian citizens, particularly those on the political left and centre. However, by the time Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany in 1933, support for unification was largely associated with the Nazis, for whom it was an integral part of their ideology. Hitler, himself an Austrian, had written in Mein Kampf about his desire to unite his birth country with Germany by any means possible.

Hitler's rise to power in Germany put pressure on Austria, and the Austrian Nazi Party began a terrorism campaign in 1933, which led to the banning of the party in Austria. In 1934, Austrian Nazis attempted a coup, assassinating the Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss. The coup failed, but the Austrian government was further destabilised, and the country became diplomatically isolated. In 1936, the Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg was forced to sign an agreement with Germany, which allowed Nazis imprisoned in Austria to be released, and for the Austrian Nazis to enter the cabinet.

In 1938, Schuschnigg attempted to reassert Austrian independence by calling a referendum on the issue. However, he was bullied by Hitler into cancelling the referendum and resigning. Hitler then ordered German troops to cross the Austrian border on 12 March 1938. They were greeted by cheering Austrians, and Hitler appointed a new Nazi government, with Arthur Seyss-Inquart as Chancellor. The next day, 13 March, Seyss-Inquart announced the abrogation of the Treaty of Saint-Germain, which prohibited the unification of Austria and Germany, and approved the replacement of the Austrian states with Reichsgaue.

The Anschluss was not universally popular in Austria, but the Nazis held a referendum on 10 April 1938, which resulted in an official approval rating of 99.7% for the union. This was achieved through coercion and manipulation, and it is estimated that, in a free referendum, only 20% of Austrians would have voted for the union.

The Anschluss was the first step in Hitler's takeover of Europe, and the international community's failure to intervene allowed his aggressive foreign policy to continue unchecked. Austria remained part of Germany until the end of World War II, when the Allied Powers declared the union void, and re-established an independent Austria.

Steiff Bears: Austrian-Made or Not?

You may want to see also

The Austrian population's support for the Nazis

The origins of Nazism in Austria have been disputed and continue to be debated. However, it is clear that the Austrian population's support for the Nazis was strong, as demonstrated by the annexation plebiscite in April 1938, which was manipulated to indicate that about 99% of Austrians wanted the union (known as the Anschluss) with Germany. The Anschluss was the Nazi regime’s first act of territorial aggression and expansion, and it was made possible by the support of the Austrian population.

The Austrian Nazi Party itself was weak and divided in the late 1920s and early 1930s, but it gained supporters as Hitler's popularity in Germany increased. The Austrian chancellor, Engelbert Dollfuss, tried to maintain Austrian sovereignty and ban the Austrian Nazi Party, but he was assassinated by Austrian Nazis in 1934. His successor, Kurt von Schuschnigg, attempted to assert Austrian independence by calling a plebiscite on March 9, 1938. However, he was pressured by Hitler to cancel the plebiscite and resign, and German troops crossed the border on March 12. The Austrian president, Wilhelm Miklas, then appointed Arthur Seyss-Inquart as chancellor, who signed the law for the "Reunification of Austria with Germany".

Germany's Invasion of Austria: What History Reveals

You may want to see also

The Austrian resistance

The main cipher of the Austrian resistance was O5, in which "O" indicates the first letter of the abbreviation of Österreich (OE), with the "5" indicating the fifth letter of the German alphabet (E). This sign may be seen at the Stephansdom in Vienna.

In addition to armed resistance, numerous individuals provided support to Jewish families during the Holocaust. These efforts included hiding individuals, managing or exchanging their property to generate funds, and aiding their escape from Nazi persecution. These actions carried immense personal risk, as assisting Jews was punishable by imprisonment or death in Nazi concentration camps. Among these individuals were Rosa Stallbaumer and her husband, Anton. Arrested by the Gestapo in 1942, they were sent to Dachau concentration camp. Although Anton survived, Rosa Stallbaumer did not; transferred to Auschwitz, she died there at the age of 44.

Military resistance in the Wehrmacht included groups such as the one led by Major Carl Szokoll, within the Wehrkreiskommando XVII. In the spring of 1945, this group planned "Operation Radetzky," which aimed to assist the Red Army in the liberation of Vienna and prevent major destruction. However, the operation was betrayed, and several members, including Robert Bernardis, Heinrich Kodré, Karl Biedermann, Alfred Huth, and Rudolf Raschke, were sentenced to death by the German "People's Court" and executed the same day.

Overall, the Austrian resistance was small but not negligible, and it played an important role in providing intelligence to the Allies and resisting Nazi rule.

Austrian Descent and Ukrainian Heritage: What's the Connection?

You may want to see also

The Soviet occupation of Austria

Soviet occupation policies in Austria were largely shaped by the Moscow Declaration of 1943, in which the British, Americans, and Soviets proclaimed that Austria was Germany's first victim. However, the declaration also stated that Austria would have to pay the price for its participation in Nazi aggression. The Soviets treated Austria as a defeated Axis power, but adhered to the line that it was a victim of Germany. This meant that Austria avoided losing territory and the ethnic cleansing that occurred in other countries.

The Soviets occupied only parts of Austria, including the capital, Vienna. Thereafter, France, Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union divided Austria into four occupation zones. The Western Allies consented to Moscow's demand that the Soviets should be entitled to German assets in Austria in their zone of occupation. This resulted in the Soviets extracting reparations through requisitions, seizing industrial plants and production installations.

The fact that Moscow did not try to impose a communist dictatorship in Austria meant that the scale of political violence experienced by Austrians was more limited than in other countries occupied by the Red Army. By 1955, when the Red Army pulled out of the country, the Soviets had arrested 2,400 Austrians, 1,250 of whom were prosecuted for war crimes and everyday criminal activity. Some 150 were executed, while others received lengthy prison terms.

The Soviets pulled out of Austria in 1955, along with the Western Allies, in exchange for Austria's promises that it would remain neutral in the Cold War.

Daycare Availability in Austria: Easy Access for Parents?

You may want to see also

The Austrian Legion

In June 1933, the Austrian government banned the Nazi Party, leading to the deportation of Theodor Habicht and the flight of around 10,000 Nazis to Bavaria, where they formed the Austrian Legion. The Legion's members received military training from the Sturmabteilung (SA), Schutzstaffel (SS), and the German Army and police. They were also armed with 10,300 rifles and 360 machine guns.

Officially part of the SA-Obergruppe VIII, designated "Austria", the Legion was commanded by SA-Obergruppenführer Hermann Reschny. It was used to cause concern in the Vienna government about potential military action from Bavaria and to smuggle Nazi propaganda into Austria. By 1935, the Legion had grown to over 14,000 members, and Berlin had provided 24 million Reichsmark in support. However, the Legion proved mostly ineffective and sometimes detrimental to German interests in Austria. Its members often lacked discipline and engaged in violent and ill-advised agitation, particularly against the Catholic Church, angering both German and Austrian authorities and even Benito Mussolini.

Following Hitler's purge of the SA in the Night of the Long Knives, the Legion was ordered to surrender its arms to the Wehrmacht, minimising the threat it posed. When the Anschluss came in March 1938, the Legion was blocked from participating and was disbanded shortly after. Most of its members returned to Germany, while those who remained in Austria faced poor job prospects.

Austria-Hungary: Understanding Austria's Historical Context

You may want to see also