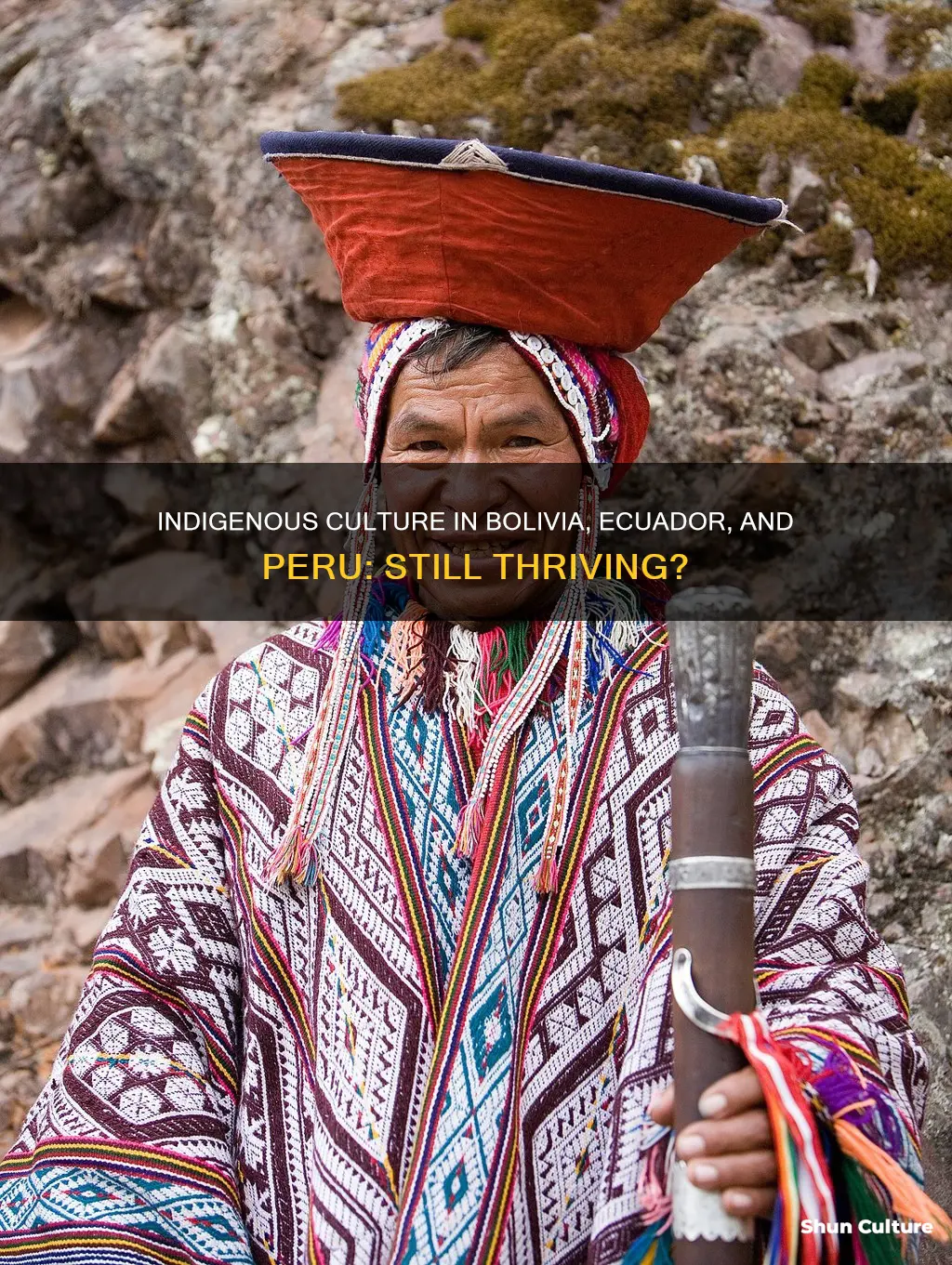

Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru are home to a rich tapestry of indigenous cultures, with a long history that dates back thousands of years. Today, these countries boast a diverse range of indigenous groups, languages, and traditions that have endured and evolved over time. Despite facing numerous challenges, including historical marginalization, political exclusion, and threats to their land rights, indigenous peoples in these countries have made significant strides towards recognition, representation, and the preservation of their unique cultural identities.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Indigenous population | 20-60% of Bolivia's population, 41% of Ecuador's population, 13% of Peru's population |

| Indigenous languages | Quechua, Aymara, Tupi-Guarani, Mohica, Chipaya |

| Indigenous communities | 36 recognized peoples in Bolivia, 38 in Ecuador, 20 in Peru |

| Indigenous land | 23 million hectares of collective property in Bolivia, 11 million hectares in Peru |

| Indigenous rights | Bolivia signed the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention in 1991, Ecuador has sign language on the official list of languages |

What You'll Learn

- Indigenous languages: Quechua, Aymara, Tupi-Guarani, and more

- Indigenous populations: 41% of Bolivia, 84% of Peru speak Spanish

- Indigenous rights: UN Declaration, ILO Convention, and more

- Indigenous protests: against resource extraction, for land rights, and more

- Indigenous women: political participation, empowerment, and more

Indigenous languages: Quechua, Aymara, Tupi-Guarani, and more

Quechua, Aymara, and Tupi-Guarani are the most widely spoken indigenous languages in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru.

Quechua

Quechua is an indigenous language family that originated in central Peru and spread to other countries of the Andes. It is the most widely spoken pre-Columbian language family of the Americas, with around 7 million speakers across South America.

Quechua was the primary language family within the Inca Empire and was tolerated by the Spanish until the Peruvian struggle for independence in the 1780s. It is now co-official in many regions and the most spoken language lineage in Peru after Spanish.

Quechua has three vowel phonemes: /a/, /i/, and /u/. There are several dialects of Quechua, including Southern Quechua (the most common dialect), Kichwa (spoken in Ecuador), and Inga Kichwa (spoken in Colombia).

Aymara

Aymara is spoken in Bolivia and Peru and to a lesser extent in Chile. It is an official language in Bolivia and Peru, where it is co-official in the areas where it is predominant.

Tupi-Guarani

Tupi-Guarani is spoken in parts of Brazil, Bolivia, and Argentina, but it is in Paraguay where it really thrives. It is an official language in Paraguay, where 95% of the population is bilingual in it.

Other Indigenous Languages

Other indigenous languages spoken in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru include Chiquitano, Guaraní, and Uro-Chipaya.

Shopping on Amazon in Bolivia: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Indigenous populations: 41% of Bolivia, 84% of Peru speak Spanish

Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru are home to a large number of indigenous peoples, who make up a significant proportion of the overall population in these countries. The indigenous peoples of South America have a long and complex history, with many groups speaking indigenous languages and maintaining their own unique cultures and traditions.

In Bolivia, indigenous peoples, or Native Bolivians, constitute anywhere from 20 to 60% of the country's population, depending on different estimates and census methodologies. The largest indigenous groups in Bolivia are the Aymara and Quechua peoples, who speak indigenous languages and have a strong cultural presence in the country. Bolivia officially recognizes 36 ethnic groups, and the country's geography includes the Andes, the Gran Chaco, and the Amazon Rainforest, which is home to many indigenous communities.

Spanish is the predominant language in Bolivia, with about 40% of the population reporting it as their mother tongue. However, the country also recognizes its many indigenous languages as official languages, with 36 specific languages listed as official, including some that are extinct. This unique feature of Bolivia's linguistic landscape is a result of the government's efforts to protect and promote indigenous rights.

In Peru, there are approximately 4 million indigenous people, comprising 55 groups and speaking 47 languages. The country's constitution stipulates that Spanish, Quechua, and Aymara are the official languages, with Quechua being the second-most spoken language in the country, and Aymara the third. Almost 3.4 million people speak Quechua, while about 0.5 million speak Aymara. These languages are predominant in the Coastal Andes area.

While the majority of Peru's population speaks Spanish (about 94.4%), the country's indigenous languages are still widely spoken, especially in rural areas and the Amazon region. The Peruvian Amazon is home to over 40 languages, with an abundance of local varieties. The indigenous peoples of Peru continue to face challenges, particularly regarding extractive activities and climate change, which threaten their traditional ways of living.

Ecuador also has a significant indigenous population, with the Kichwa people of Ecuador speaking the Kichwa dialect of Quechua. The adoption of Quechua by the Cañari people is an example of the language's historical influence in the region.

In summary, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru have large and diverse indigenous populations, with varying levels of Spanish-language adoption. The countries have taken steps to recognize and protect indigenous rights, and indigenous languages and cultures continue to play an important role in these societies.

Bolivians: A Diverse Mix of Indigenous and European Heritage

You may want to see also

Indigenous rights: UN Declaration, ILO Convention, and more

Indigenous rights have been a topic of discussion and legislation for decades, with international organisations such as the United Nations (UN) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) at the forefront of these efforts. The rights of Indigenous peoples in Latin America, including Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru, have been a particular focus.

ILO Convention No. 169:

The ILO, an agency of the League of Nations and later the UN, has played a pivotal role in advocating for Indigenous rights. In 1957, it adopted the Indigenous and Tribal Populations Convention (No. 107), which was the first international instrument to specifically address the human rights of Indigenous peoples. However, this convention had a problematic assimilationist perspective, characterising Indigenous cultures as "less advanced" and suggesting that the "loss of tribal characteristics" was inevitable. Despite its shortcomings, Convention 107 took important steps toward equality by discouraging forced assimilation, acknowledging Indigenous land rights, and prioritising education in Indigenous languages.

In response to criticism and evolving perspectives, the ILO re-examined and revised Convention 107 during 1988-1989, resulting in the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169). This updated convention is a major binding international agreement that protects the rights of Indigenous and tribal peoples. It recognises their aspirations to control their institutions, ways of life, economic development, and to maintain their identities, languages, and religions within their respective nations.

UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples:

The efforts of the ILO laid the groundwork for the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which was adopted in 2007. This declaration represents a significant milestone in the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous peoples worldwide.

Other Notable Agreements:

In addition to the ILO and UN conventions, there have been other agreements and declarations that address Indigenous rights in Latin America:

- The Inter-American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (Draft 1995 and Draft 1997) by the Organization of American States (OAS)

- The Peace Process in Guatemala (1995) and the Chiapas Agreements in Mexico (1996) incorporated references to ILO Convention No. 169

- Ecuador's 1998 Political Constitution includes provisions related to Indigenous rights

Bolivia: A Nation State? Understanding Its Complex Identity

You may want to see also

Indigenous protests: against resource extraction, for land rights, and more

Indigenous peoples in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru have been at the forefront of social and political mobilisation in recent years, advocating for their rights and land protection. In Bolivia, for instance, the 1990 March for Territory and Dignity played a pivotal role in uniting Indigenous communities and influencing the 1996 forestry law, which recognised their legal right to manage their forests. However, in the late 2000s and early 2010s, Indigenous protests erupted once more in response to government-backed resource extraction projects and erosion of their land rights.

Bolivia

In 2011, the Bolivian government proposed the construction of a highway through the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory, known as TIPNIS, which is the ancestral land of over 12,000 indigenous residents from the Chimane, Yuracaré, and Mojeño-Trinitario peoples. This sparked a series of demonstrations, with protesters marching from Trinidad, Beni, to the national capital of La Paz, beginning on 15 August 2011. The highway project was supported by domestic migrants, highland indigenous groups, and the government, who argued it would boost the economy and reduce travel time. However, the lowland indigenous groups opposed the project, fearing deforestation, land grabs, and an "invasion" of migrants following the construction.

The protests turned violent, with a crackdown by security forces on 24 September 2011, resulting in four deaths. This led to the resignation of the Defense Minister, María Chacón Rendón, and the Interior Minister, Sacha Llorenty. Despite the government's suspension of the project, protesters continued their march, demanding its cancellation and the resignation of President Evo Morales. On 25 September, police fired tear gas and detained protesters in the Yucomo region, resulting in several injuries and four deaths. Solidarity protests erupted in other parts of Bolivia, including La Paz, Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, and Beni.

The 2011 protests in Bolivia highlighted the ongoing tensions between the government's pursuit of economic development and the Indigenous communities' fight for land rights and environmental protection.

Ecuador

Ecuador has also witnessed recurrent cycles of violence and protests over Indigenous rights. In June 2022, Indigenous organisations, led by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), staged anti-government protests in response to the government's lack of action on their demands. Among their requests were the guarantee of Indigenous peoples' collective rights, intervention to lower food and essential goods prices, and the mitigation of social and environmental impacts of mining and oil extraction in Indigenous territories.

The protests began peacefully but escalated into violence, with some protesters looting and vandalising property and blocking the delivery of essential supplies to hospitals. Security forces responded with excessive force, resulting in the deaths of five civilians and one military member, and over 300 injuries. While the government took initial steps to address some of the concerns, such as reducing fuel prices and increasing the budget for intercultural education, the cycle of violence and abuse during anti-government protests in Ecuador persists, highlighting the need to address the root causes and ensure accountability for abuses.

Peru

Peru has been experiencing a political and civil crisis, with weeks of protests triggered by the removal from power of former leader Pedro Castillo. While the immediate spark was Castillo's attempt to shut down Congress to prevent his impeachment, the crisis has deeper roots in the country's political system, the dismantling of established political parties, and deep polarisation along ethnic, racial, economic, and regional lines.

The protests in Peru are led primarily by Castillo supporters, particularly from the Quechua and Aymara Indigenous groups in the south of the country, who share close ties with the same groups in Bolivia. Evo Morales, the former president of Bolivia, has been accused of stirring up the protests, and there are similarities in the tactics employed, such as road blockades and violence against police. However, the protest movement in Peru goes beyond Morales' influence, reflecting the mobilising capacity of Indigenous people and their determination to demonstrate strength and advance the concept of "runasur," or uniting Indigenous people across the Andes region.

The demands of the protesters in Peru include forcing the government to agree to a constituent assembly to create a new constitution and seeking the resignation of Castillo's replacement, Dina Boluarte. The movement has gained vocal support from the Latin American left, and while it may not have the backing of urban areas in the north, it has exposed deep divisions within the country.

US Citizens: Yellow Fever Vaccine for Bolivia?

You may want to see also

Indigenous women: political participation, empowerment, and more

Indigenous women in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru have historically been marginalised and underrepresented in politics. However, in recent decades, there has been a surge in political mobilisation and participation by Indigenous women in these countries, leading to increased social and political inclusion.

In Bolivia, Indigenous women have made significant strides in political participation and empowerment. The National Confederation of Campesino Women of Bolivia Bartolina Sisa, commonly known as "Las Bartolinas", is a national Indigenous women's organisation with an estimated 1.5 million members, making it the country's most influential women's group. The Bartolinas played a pivotal role in advancing Indigenous women's status during the presidency of Evo Morales, Bolivia's first Indigenous president. Morales' government passed several reforms recognising Indigenous rights and promoting gender equality, such as the 2009 constitution, which guaranteed Indigenous peoples the right to self-governance and autonomy.

One notable example of the growing political influence of Indigenous women in Bolivia was the 400-kilometre Women's March to La Paz in December 1995, led by Indigenous coca-growing women, known as "cocaleras". These women played a crucial role in the formation of the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) political party, which eventually brought Evo Morales to power. The cocaleras have continued to hold leadership positions within the Bartolinas and have been instrumental in advocating for Indigenous women's rights and representation.

In Peru, Indigenous women have also actively participated in contested politics and social movements. Women like Carmela Giraldo and Aida Aroni Chilcce have bravely spoken out against authoritarian governments, police brutality, and social injustice. Despite facing violent repression, racism, and discrimination due to their political participation, Indigenous women in Peru continue to mobilise and demand social justice, equality, and inclusion.

Indigenous women in Ecuador have similarly engaged in political activism and social movements to address issues of inequality and discrimination. While specific information on their political participation is scarce, it is known that Indigenous women in Ecuador have played a crucial role in advocating for their rights and representation. They have joined forces with other marginalised groups, such as peasants, students, and workers, to protest against oppressive conditions and demand social and political change.

Despite the progress made, Indigenous women in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru still face significant challenges in achieving full political participation and empowerment. Violence, racism, and discrimination remain prevalent, and the implementation of laws protecting Indigenous women's rights is often inadequate. Nonetheless, the resilience and determination of these women to fight for their rights and representation continue to drive social and political change in their respective countries.

Bolivia: A Place to Avoid?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The main indigenous groups in these countries include the Quechua, Aymara, Chiquitano, Guaraní, and Moxeño.

In Bolivia, 41% of the population over 15 years old is indigenous, while in Peru, this number is estimated to be between 8% and 10%. Ecuador's exact percentage is unknown, but the country has around 24 indigenous languages.

Indigenous peoples in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru face various challenges, including seismic work for oil and gas exploration, hydroelectric projects, and land rights issues. Additionally, as many as 15 of Bolivia's 36 indigenous communities are at risk of extinction due to systematic neglect, social exclusion, and geographic isolation.

All three countries have taken steps to recognize and protect the rights of their indigenous peoples. Bolivia has adopted the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and a new Constitution, becoming a plurinational state. Peru has made Quechua its second official language, and Ecuador has Kichwa umbrella organizations that promote nation-building.