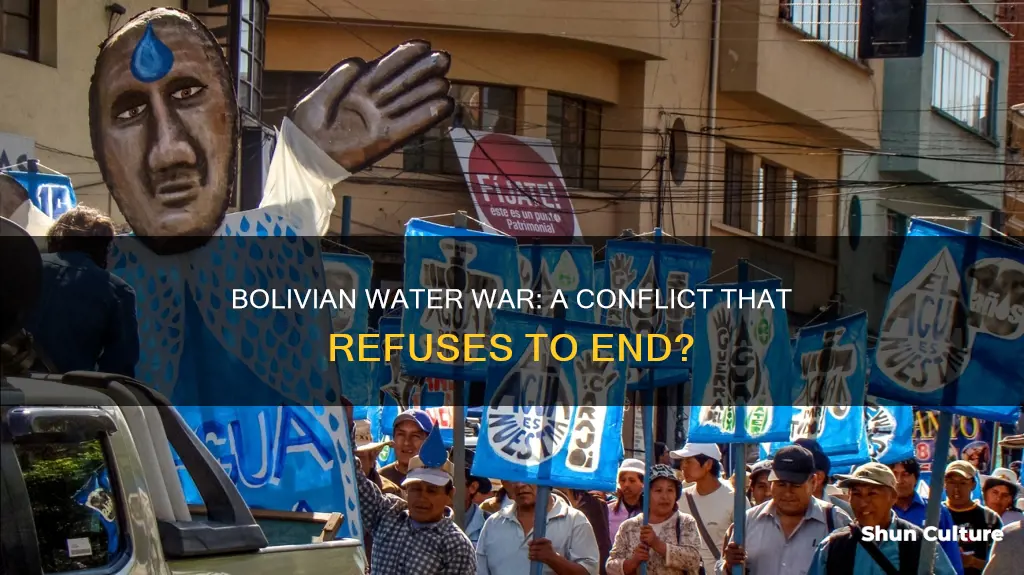

The Bolivian Water War, also known as the Cochabamba Water War, was a series of protests that took place in Cochabamba, Bolivia's fourth-largest city, between December 1999 and April 2000. The conflict was sparked by the privatisation of the city's municipal water supply company, SEMAPA, which led to drastic increases in water rates. The protests, which were met with police violence, culminated in a historic victory for the residents of Cochabamba, as the national government agreed to reverse the privatisation of the water supply. While the immediate conflict ended in 2000, the underlying issues of water scarcity and inequality in Bolivia persist, and the country continues to face challenges in ensuring access to water for all its citizens.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date | December 1999-April 2000 |

| Location | Cochabamba, Bolivia |

| Reason | Privatization of the city's municipal water supply company, SEMAPA |

| Protesters | Regantes (peasant irrigators), jubilados (retired unionized factory workers), Bolivian citizens, pieceworkers, sweatshop employees, street vendors, anarchists, homeless street children |

| Protest Actions | Shut down the city for four days, erected roadblocks, clashed with police, blocked highways, demanded unemployment resolution |

| Government Actions | Passed Law 2029, declared a "state of siege", arrested protest leaders, used tear gas and rubber bullets |

| Outcome | The national government reached an agreement with the Coordinadora to reverse the privatization, Aguas del Tunari left Cochabamba |

| Casualties | 6 dead, dozens injured and forcibly detained |

What You'll Learn

- The Bolivian Water War was sparked by the privatisation of Cochabamba's water system

- The conflict was between civilians and the army, with hundreds arrested and several killed

- The World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) pressured Bolivia to privatise water

- The water consortium, Aguas del Tunari, was dominated by the Bechtel Corporation

- Bechtel withdrew from Bolivia after the uprising, but sought compensation

The Bolivian Water War was sparked by the privatisation of Cochabamba's water system

The privatisation of Cochabamba's water system was a highly controversial issue in Bolivia, sparking the Bolivian Water War, also known as the Cochabamba Water War. The conflict, which took place between December 1999 and April 2000, was a series of protests in response to the privatisation of the city's municipal water supply company, SEMAPA. The protests were largely organised by the Coordinadora (Coalition in Defense of Water and Life), a community coalition.

The privatisation of the water system in Cochabamba was a result of the Bolivian government's economic policies. Facing economic hardship, the government sought financial support from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). As a condition for receiving loan assistance, the World Bank and IMF required the Bolivian government to privatise state industries and increase private investment. Within this context, many national industries, including the water system in Cochabamba, were privatised.

The water rights of Cochabamba were sold to the private company Aguas del Tunari, a consortium between the British firm International Waters and several other companies, including United Utilities from the UK and Abengoa from Spain. Aguas del Tunari was granted a $2.5 billion, 40-year concession to "provide water and sanitation services to the residents of Cochabamba, as well as generate electricity and irrigation for agriculture." The consortium was guaranteed a minimum 15% annual return on its investment.

The privatisation of the water system in Cochabamba led to a significant increase in water rates. Aguas del Tunari raised water rates by an average of 35%, with some residents reporting even higher increases. For many residents, this meant that their water bills doubled or tripled. The rate hikes were particularly burdensome for low-income households, who often had to resort to developing their own wells and water systems to cope with the increased costs.

The protests against the privatisation of the water system in Cochabamba began in January 2000, with peaceful demonstrations and marches led by the Coordinadora. However, the protests turned violent in February 2000, when military police from La Paz, Bolivia, were sent to suppress the demonstrations. A 'state of siege' was declared by the Bolivian President, and the violence resulted in several deaths, injuries, and arrests.

The Bolivian Water War attracted international attention and coverage, with activists protesting during the IMF and World Bank meetings in Washington, D.C. In April 2000, the national government reached an agreement with the Coordinadora to reverse the privatisation of the water system in Cochabamba. The contract with Aguas del Tunari was revoked, and the water management was handed over to the Coordinadora.

Exploring Bolivia: Getting to Samaipata

You may want to see also

The conflict was between civilians and the army, with hundreds arrested and several killed

The conflict between civilians and the army in the Bolivian Water War, also known as the Cochabamba Water War, resulted in several arrests and fatalities. The protests, which took place in Cochabamba, Bolivia's fourth-largest city, occurred between December 1999 and April 2000. The demonstrations were sparked by the privatisation of the city's municipal water supply company, SEMAPA, and the subsequent increase in water rates.

The conflict escalated when Aguas del Tunari, the new company managing the water supply, raised water rates by an average of 35%, which was unaffordable for many residents. In response, thousands of protesters, including peasant irrigators, retired unionised factory workers, and Bolivian citizens, took to the streets. The demonstrators halted the city's economy by holding a general strike that shut down Cochabamba for four days.

The Bolivian government responded by sending troops and law enforcement from Oruro and La Paz to confront the protesters. On February 4, 2000, clashes between demonstrators and security forces resulted in injuries to both protesters and police officers. The government also imposed a "state of siege," which allowed for the arrest and detention of individuals without warrants and the restriction of travel and political activity.

During the protests, there were several instances of violence and arrests. On April 8, 2000, a 17-year-old boy, Victor Hugo Daza, was shot and killed by a Bolivian Army captain who opened fire on a crowd of demonstrators. This incident further fuelled the anger of the protesters. Additionally, the leaders of the Coordinadora, including Óscar Olivera, were arrested when they went to meet with the governor to discuss the water rate hikes.

The conflict led to a significant number of arrests. On February 4 and 5, 2000, almost 200 demonstrators were arrested during the clashes with security forces. On April 9, 2000, 800 striking police officers fired tear gas at soldiers, leading to a government response of granting a 50% pay raise to the La Paz police.

The conflict also resulted in several fatalities. In addition to the death of Victor Hugo Daza, there were reports of five deaths during the violent clashes between demonstrators and law enforcement. On April 9, 2000, near the city of Achacachi, soldiers opened fire on protesters resisting the removal of a roadblock, killing two people, including a teenage boy. Angry residents retaliated by attacking and killing army captain Omar Jesus Tellez Arancibia.

The Bolivian Torch: A Guide to Growing This Rare Cactus

You may want to see also

The World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) pressured Bolivia to privatise water

Bolivia is South America's poorest country and has one of the world's most controversial water privatisation programs. In 1985, with hyperinflation at an annual rate of 25,000%, few foreign investors would do business in the country. The Bolivian government turned to the World Bank as a last resort against economic collapse.

The World Bank and the International Development Bank highlighted water privatisation as a requirement for the Bolivian government to retain ongoing state loans. The World Bank said that "poor governments are often too plagued by local corruption", and similarly stated that "no subsidies should be given to ameliorate the increase in water tariffs in Cochabamba".

In 1998, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved a $138 million loan for Bolivia to help the country control inflation and boost economic growth. In compliance with IMF-drafted "structural reforms" for the nation, Bolivia agreed to sell off all remaining public enterprises, including Cochabamba's local water agency, SEMAPA. The World Bank acknowledged that it provided assistance to prepare a concession contract for Cochabamba in 1997.

In September 1999, after closed-door negotiations, the Bolivian government signed a $2.5 billion, 40-year contract to hand over Cochabamba's municipal water system to Aguas del Tunari, a multinational consortium of private investors. The deal was seen as unthinkable to the leaders who felt pressured to keep the trust of international investors.

In 2000, Bechtel made an annual revenue of over $14 billion, while Bolivia's national budget at the time was only $2.7 billion. Bechtel was eventually forced out of the country, dealing a serious blow to foreign investment in Bolivia.

A Direct Route to Uyuni, Bolivia: Travel Tips

You may want to see also

The water consortium, Aguas del Tunari, was dominated by the Bechtel Corporation

Aguas del Tunari was the sole bidder for the privatisation of Cochabamba's water system. The consortium was awarded a 40-year concession to provide water and sanitation services to the residents of Cochabamba, as well as generate electricity and irrigation for agriculture. The contract was worth $2.5 billion.

The consortium's involvement in Cochabamba's water system was short-lived, however. In April 2000, the Bolivian government rescinded its contract with Aguas del Tunari following protests over water prices. The consortium pursued arbitration, seeking compensation for the termination of its contract. In January 2006, a settlement was reached between the Bolivian government and the international shareholders of Aguas del Tunari, and the shareholders withdrew their financial claims against Bolivia.

Bolivia's Dynamic Borders: Evolution and Changes Explored

You may want to see also

Bechtel withdrew from Bolivia after the uprising, but sought compensation

The Bolivian Water War, also known as the Cochabamba Water War, was a series of protests that took place in Cochabamba, Bolivia's fourth-largest city, between December 1999 and April 2000. The protests were sparked by the privatisation of the city's municipal water supply company, SEMAPA, and the subsequent rate hikes implemented by the new firm, Aguas del Tunari, a joint venture involving Bechtel.

In response to the protests, the Bolivian government declared a "state of siege", similar to martial law, which allowed for the arrest and detention of individuals without warrants and the restriction of travel and political activity. The government's response led to further protests and the situation escalated, with one civilian killed and several others injured.

On 10 April 2000, the national government reached an agreement with the Coordinadora, a community coalition that organised the protests, to reverse the privatisation of SEMAPA. However, the conflict between the Bolivian government and Bechtel continued even after the company left the country.

Bechtel, along with its chief co-investor Abengoa of Spain, sought compensation for lost profits and damages following their departure from Bolivia. They filed a case with the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), a tribunal administered by the World Bank, claiming that the Bolivian government had violated a bilateral trade agreement with the Netherlands when it revoked the consortium's water contract. Bechtel and Abengoa initially sought $50 million ($25 million in damages and $25 million in lost profits) but eventually settled for a token payment of thirty cents.

The case was highly controversial, with citizen groups from around the world protesting the secrecy of the proceedings and the exclusion of the Bolivian public and media. Despite the global pressure, the process moved forward, with the selection of a tribunal of arbitrators to resolve the dispute. However, in January 2006, a settlement was reached between the Government of Bolivia and Aguas del Tunari, in which the shareholders withdrew their financial claims against Bolivia.

Bolivia's Turbulent Times: Unrest and Political Chaos

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Bolivian Water War, also known as the Cochabamba Water War, was a series of protests that took place in Cochabamba, Bolivia, between December 1999 and April 2000. The protests were in response to the privatisation of the city's municipal water supply company, SEMAPA, and the subsequent increase in water rates.

The Bolivian Water War was sparked by the privatisation of Cochabamba's water system, which was taken over by a private consortium dominated by the Bechtel Corporation of San Francisco. Bechtel had raised water rates, and protestors blamed the company for trying to "lease the rain".

The Bolivian Water War resulted in a historic victory for the residents of Cochabamba. After four days in hiding, Oscar Olivera, a leader of the protests, signed an agreement with the Bolivian government that guaranteed the withdrawal of Aguas del Tunari (the consortium that had taken over Cochabamba's water system) and granted control of the city's water to La Coordinadora, a grassroots coalition led by Olivera. The agreement also assured the release of detained protesters and promised the repeal of water privatisation legislation.

No, the Bolivian Water War is not still going on. The protests took place between December 1999 and April 2000, and the outcome was a victory for the residents of Cochabamba, who regained control of their water system. However, Bolivia continues to face issues related to its water supply, including droughts and water scarcity.