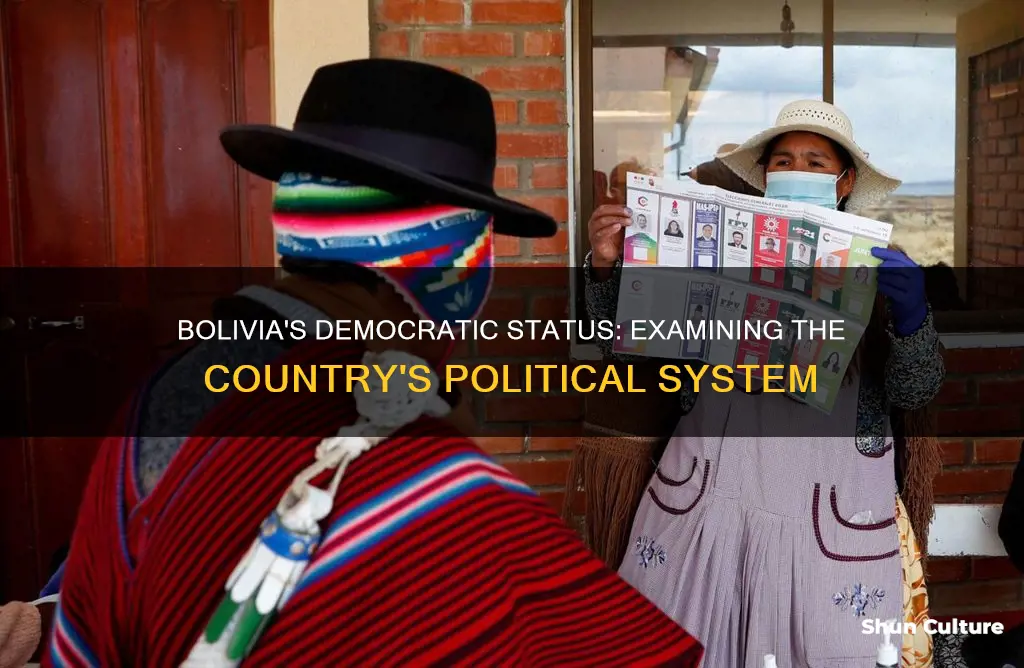

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a unitary republic with a representative democratic government. The country is divided into 9 departments, 112 provinces, 327 municipalities and 1,384 cantons. Bolivia's legislative assembly is bicameral, with a House of Representatives and a Senate. The country gained independence in 1825 and has since experienced a tumultuous political history, with a succession of military and civilian governments. Bolivia's modern democratic status is a matter of debate, with some arguing that the country is a perfect democracy and others asserting that it falls short of democratic ideals.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Democracy | Bolivia is a representative democracy with a history of political instability and military coups. |

| Independence | Bolivia gained independence in 1825. |

| Government | Bolivia is a unitary, democratic, representative, and presidential republic. |

| Head of State | Luis Arce |

| Population | 9,427,219 |

| Language | Spanish, Quechua, Aymara, and Tupiguarani |

| Political Division | 9 Departments, 12 Provinces, and 324 Municipalities |

| Capital | Sucre (constitutional capital) and La Paz (seat of government) |

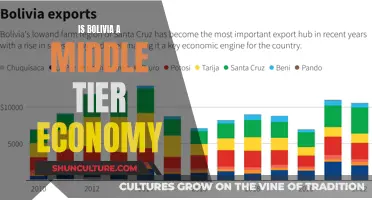

| Economic System | Bolivia has a mixed economy with a focus on exporting gas and minerals. |

| Social Issues | Bolivia has issues with poverty, inequality, and marginalization of indigenous and Afro-Bolivian populations. |

| Political Parties | The main parties include MAS (Evo Morales' left-wing party) and the fragmented opposition. |

| Recent Events | Protests and political instability following the 2019 presidential election and the 2025 candidacy of Evo Morales. |

What You'll Learn

Bolivia's democratic status

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a unitary republic with a representative democratic government. It is a landlocked country located in central South America. Bolivia's democratic status is complex and has a history of political instability.

History

Bolivia gained independence in 1825, but its subsequent history has been marked by economic crises, military coups, counter-coups, and the influence of caudillos (local strongmen). Despite transitioning to democracy in 1982, Bolivia continued to experience problems of poverty, social inequality, and the marginalization of indigenous and Afro-Bolivian populations.

Recent Events

In 2019, Bolivia underwent a period of crisis following serious irregularities in the presidential elections. The incumbent, Evo Morales, was forced to resign and leave the country. Protests for and against the government ensued, resulting in dozens of deaths and hundreds of injuries.

Current Status

Bolivia has a mixed record when it comes to democratic performance. On the one hand, it exhibits mid-range performance across various categories of democratic frameworks, with relatively higher scores in participation. On the other hand, issues such as systemic corruption, polarization, and anti-democratic practices continue to plague the country.

Bolivia's current government, led by President Luis Arce since 2020, has been accused of suppressing measures against journalists and the media, and criminal proceedings against opposition leaders and election officials continue.

While Bolivia has a democratic form of government on paper, in practice, it faces challenges in upholding democratic ideals and ensuring the protection of human rights. The country's democratic status remains a work in progress, with efforts needed to address issues like inequality, discrimination, and the marginalization of certain populations.

Exploring Bolivia's Presidential Term Limits

You may want to see also

The 2019 coup

On 10 November 2019, Bolivia was shaken by a coup d'état. President Evo Morales, a titan of the Latin American left, was forced from office by the Bolivian military and forced to flee the country after weeks of civil protests disputing the authenticity of his election victory. Morales had been declared the winner of the 2019 Bolivian general election, but the result was disputed, and an audit by the Organization of American States (OAS) found significant irregularities in the electoral process. Morales resigned after the military and police, along with the Bolivian Workers' Center (COB), recommended he do so. The second vice president of the Senate, opposition senator Jeanine Áñez, then assumed the role of president on 12 November.

The OAS alleged multiple irregularities, including failures in the chain of custody for ballots, alteration and forgery of electoral material, redirection of data to unauthorised servers, and data manipulation. They added that it was statistically unlikely that Morales had secured the 10-percentage-point margin of victory needed to win outright, and that the election should be annulled. An analysis by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) disputed the OAS's preliminary findings, arguing that a basic coding error resulted in inexplicable changes in the trend.

Morales and his supporters argued that the event was a coup d'état. International politicians, scholars and journalists were divided between describing the event as a coup or popular uprising. Morales called for the Bolivian people to reject the leadership of Áñez, and protests to reinstate Morales as president continued, becoming highly violent. The protests were met with violence by security forces after Áñez exempted police and military from criminal responsibility in operations for "the restoration of order and public stability".

In August 2021, a report commissioned by the OAS and carried out by independent human rights experts concluded that the Añez government's path to power came with "irregularities" and serious human rights abuses by security forces. In June 2022, the Bolivian courts convicted Áñez for charges committed during the political crisis. She was sentenced to ten years in prison.

Sucre, Bolivia: A Historical Gem in South America

You may want to see also

The role of the OAS

The Organization of American States (OAS) played a significant role in the 2019 coup in Bolivia, which saw the overthrow of the country's first indigenous president, Evo Morales. On 21 October 2019, the OAS Electoral Observation Mission in Bolivia issued a statement expressing "deep concern and surprise" regarding the change in the trend of preliminary election results. The OAS report called for a second round of voting, contradicting the official results that gave Morales a ten-point lead over his closest contender, avoiding a runoff.

The OAS's statement was not supported by evidence and was widely interpreted as an allegation of fraud against Morales. This allegation gained traction in the media and became one of the most-used justifications for the military coup. The OAS's actions had far-reaching consequences and contributed to the political conflict in the country.

The OAS's behaviour has been criticised by various groups, including human rights experts and academics. They argue that the OAS's claims were flawed and that the organisation should retract its misleading statements. Additionally, there have been calls for an investigation into the OAS's role in the coup, with some suggesting that the organisation should be held accountable for its actions.

The OAS's actions in Bolivia must be understood in the context of the region's polarised international politics. The OAS's Secretary General, Luis Almagro, has been accused of supporting the de facto government that came to power after the coup. Almagro refused to acknowledge the coup and ignored allegations of human rights violations. He also persisted in the fraud narrative regarding the 2019 elections, even though multiple academic studies have debunked the OAS's claims.

The OAS's role in Bolivia highlights the organisation's influence in the region and its potential to destabilise democratic processes. The aftermath of the 2019 coup and the OAS's actions continue to impact Bolivia's political landscape, with ongoing protests and social unrest.

Bolivia's Salt Flats: A Natural Wonder in South America

You may want to see also

The Morales government

Morales' government prioritized constitutional reforms to promote equitable social policies and indigenous rights. However, it also deepened state control of the economy, including the nationalization of energy and communications companies, and concentrated power in the executive, undermining checks on presidential power.

Morales' government oversaw strong economic growth, with GDP increasing from $9 billion to over $40 billion during his tenure. The government also reduced extreme poverty levels from 38% to 15% and tripled GDP per capita. Additionally, they improved social spending, introducing non-contributory old-age pensions, payments to mothers, and the Bono Juancito Pinto program, which provided $29 per year to parents whose children maintained an 80% attendance rate in public school.

Morales' supporters laud him as a champion of indigenous rights, anti-imperialism, and environmentalism. However, critics point to democratic backsliding during his tenure, arguing that his policies sometimes failed to reflect his environmentalist and indigenous rights rhetoric, and that his defense of coca contributed to illegal cocaine production.

Exploring Bolivia's Mountainous Landscape: A South American Adventure

You may want to see also

Current political instability

Bolivia has been described as a partly-free democracy by Freedom House, with a score of 66/100 as of 2023. The country has a history of political instability, with a succession of military and civilian governments until the election of Evo Morales in 2006. Under Morales, Bolivia experienced significant economic growth and political stability but was also accused of democratic backsliding and described as a competitive authoritarian regime.

In 2019, Bolivia was shaken by a coup d'état, with President Evo Morales forced from office by the military and fleeing the country after weeks of civil protests questioning the authenticity of his electoral victory. The coup was fueled by a report from the Organization of American States (OAS), which claimed that irregularities were visible in the electoral data and thus interference by Morales' party was likely the cause of his victory. However, the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) published a report casting doubt on these claims, stating that the available data appeared consistent with Morales' victory.

The new President installed in November 2019, Jeanine Áñez, associated herself with fascists and engaged in human rights abuses, including discrimination against indigenous peoples and assaults on protestors. Despite initially stating that she would not stand as a candidate in the upcoming election, Áñez reneged on that promise and ran for president.

Bolivia has a history of political repression, with a recent example being the case of Santa Cruz Governor Luis Fernando Camacho, who was detained on charges of terrorism due to his alleged scheming to secure the resignation of Morales in 2019. Human Rights Watch reviewed the charging documents and found no supporting evidence for the terrorism charge.

The country's justice system has been exploited to accommodate the interests of the ruling political power, and President Luis Arce has failed to fulfill his promise of judicial reform to make the system independent of politics. Almost 50% of judges in Bolivia remain "temporary," and almost 80% of prosecutors were also temporary as of December 2022.

Bolivia's judiciary is highly politicized and hampered by corruption. There is also a lack of independence in the media, with journalists facing harassment and intimidation, including from government officials.

In terms of economic and social rights, official data showed that some 36% of Bolivians fell below the national poverty line and 11% were considered extremely poor as of 2021. Inequality has decreased over the years, but child labor and violence against women remain persistent problems.

Bolivia's Government: A Deep Dive into Democracy

You may want to see also