Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a state in the southeast of Germany. It is the largest German state by land area and the second most populous. Bavaria has a distinct culture, largely because of its Catholic heritage and conservative traditions, which includes a language, cuisine, architecture, festivals, and elements of Alpine symbolism. In 1925, 70% of the Bavarian population was Catholic, but as of 2020, this number has dropped to 46.9%. Bavarians commonly emphasize pride in their traditions, including traditional costumes, centuries-old folk music, and traditional sports disciplines.

What You'll Learn

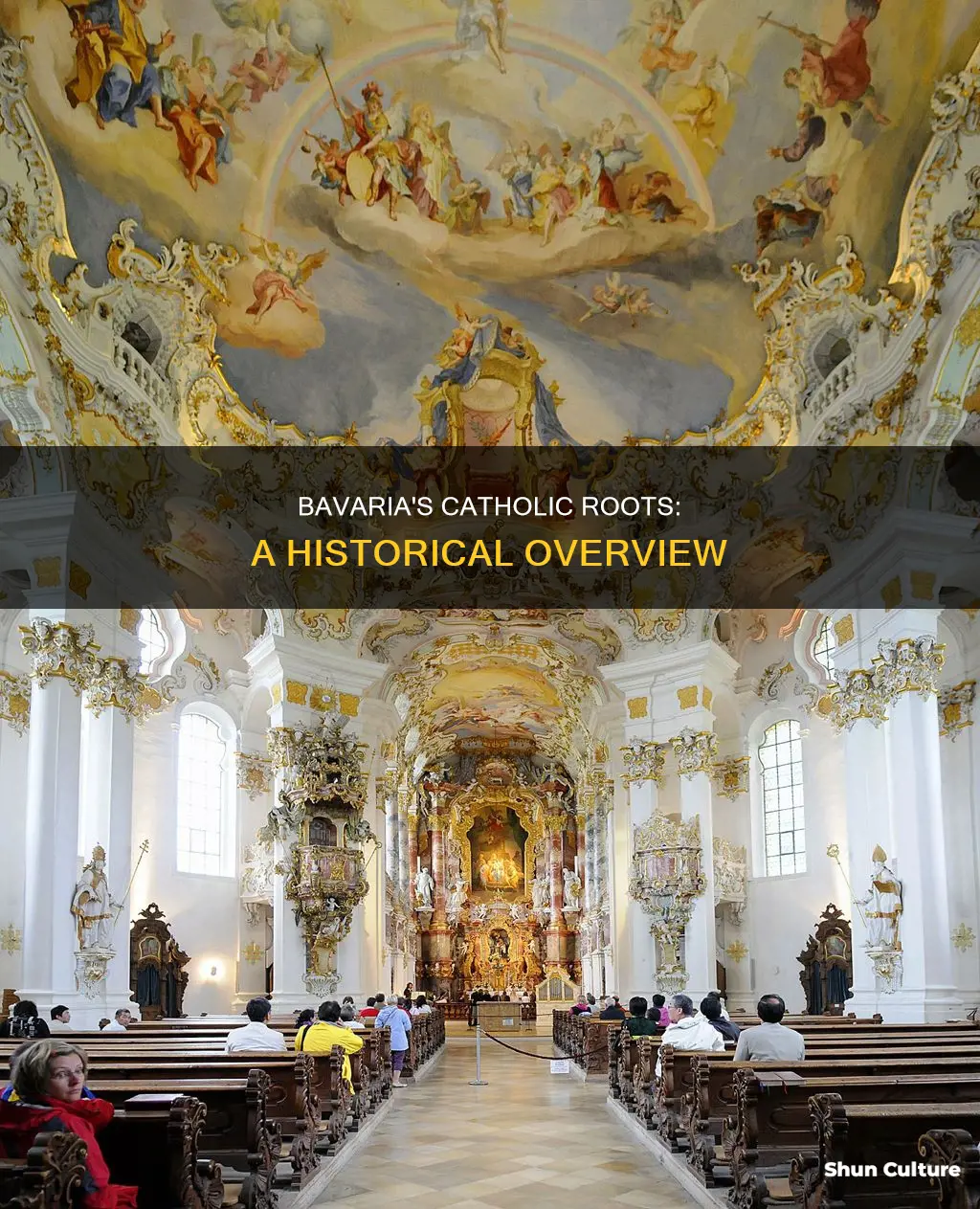

Bavaria's Catholic heritage

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a state in the southeast of Germany. It has a distinct culture, largely because of its Catholic heritage and conservative traditions, which includes a language, cuisine, architecture, festivals and elements of Alpine symbolism.

Bavaria has a long and predominant tradition of Roman Catholic faith. In 1925, 70.0% of the Bavarian population was Catholic, 28.8% was Protestant, 0.7% was Jewish, and 0.5% was placed in other religious categories. As of 2020, 46.9% of Bavarians adhered to Catholicism (a decline from 70.4% in 1970). Bavarians commonly emphasize pride in their traditions, including traditional costumes collectively known as Tracht, such as Lederhosen for males and Dirndl for females.

Bavaria was conquered by the Roman Empire in the 1st century BC, when the territory was incorporated into the provinces of Raetia and Noricum. Saint Boniface, the "Apostle of Germany", completed the people's conversion to Christianity in the early 8th century. In the 12th century, the Duchy of Bavaria was awarded as a fief to the Wittelsbach family, who ruled for 738 years, from 1180 to 1918. In 1506, the other parts of Bavaria were reunited, and Munich became the sole capital. The country became a centre of the Jesuit-inspired Counter-Reformation.

In the 19th century, Bavaria became a kingdom in 1806 and joined the Confederation of the Rhine. It joined the Prussian-led German Empire in 1871 while retaining its title of kingdom. As Bavaria had a heavily Catholic majority population, many people resented being ruled by the mostly Protestant northerners in Prussia. As a direct result of the Bavarian-Prussian feud, political parties formed to encourage Bavaria to break away and regain its independence.

In 1949, Bavaria became part of the Federal Republic of Germany, despite the Bavarian Parliament voting against adopting the Basic Law of Germany, mainly because it was seen as not granting sufficient powers to the individual states. Thus, during the Cold War, Bavaria was part of West Germany.

Exploring Bavaria by Train: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Catholic rituals and festivals

Bavaria is home to a plethora of Catholic rituals and festivals, with Roman Catholicism being the predominant religion of Old Bavaria, making up 69.9% of the population in 1970.

Rituals

Catholicism in Bavaria is not considered "ultra-orthodox", with many practising their religion privately and not in public. However, there are still many rituals that are observed, especially in smaller towns and villages. For example, Bavarians observe the religious death rituals found in the Roman Catholic liturgy, such as publishing death notices in the local press and holding memorials for the first year after a person's death.

Festivals

Bavaria has fourteen official holidays, more than any other German state. Religious festivals have always been an integral part of life in Old Bavaria, with the three-day harvest festival, Kirchweih, being one of the most significant. This festival was so economically disruptive that, in 1803, all Kirchweih feasts were legally required to be celebrated within the same three-day period, a practice that continues to this day. Fasching, the Bavarian version of carnival, is another festival that takes place annually, beginning in early January.

In addition to the regular church holidays such as Easter, Christmas, and Pentecost, Bavaria also celebrates its patron saints of markets, artisan groups, and other organisations. One of the most famous festivals is the Oberammergau Passion Play, which has been included in UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage List. This play depicts the passion and death of Christ and is performed by over 2,000 local actors every ten years.

Other notable festivals include the Kaltenberg Jousting Tournament, the Burghausen Castle Festival, the Trenck Festival, the Drachenstich Festival at Furth, and the Neuburg Palace Festival. Many of these festivals include historical re-enactments, parades, music, dancing, and traditional food and drink.

Crafting a Tiered Cake with Bavarian Cream Filling

You may want to see also

Catholic population decline

While Bavaria is a predominantly Catholic region, the Catholic population is declining globally, especially in Europe and the Americas. In the United States, for instance, the percentage of Catholics has decreased from 24% in 2007 to 21% in 2014. This decline is attributed to various factors, including the impact of sexual abuse scandals within the Church and the rise of other religions, such as Protestantism.

According to a Pew survey, while 32% of Americans were raised Catholic, only 21% continue to identify as such. This shift away from Catholicism is more pronounced than the decline in Protestantism in the US. The median age of US Catholics is 49, compared to 40 for members of other religions and 36 for the country as a whole. This indicates that younger generations are increasingly less likely to identify as Catholic.

The decline in the Catholic population is also evident in church attendance. In the US, Catholic church attendance has decreased by six percentage points over the past decade. While 45% of Catholics attended church weekly from 2005 to 2008, this number dropped to 39% from 2014 to 2017. The steepest decline occurred between the 1950s and 1970s, coinciding with a rise in religious alternatives and societal changes.

The situation is similar in other countries, including Ireland, where the Catholic identity is fading, and Australia, where sexual abuse allegations have shaken the Church. The Church's image among people under 30 has suffered, and the next generation of priests and parishioners may not be there to sustain the institution.

However, it is important to note that the decline is not uniform globally. In Africa, for instance, Catholicism continues to grow, offsetting the declines in other regions. Nonetheless, the overall trend suggests a challenging future for the Catholic Church, particularly in addressing the decline in membership and the impact of scandals on its reputation.

Traveling to Bavaria? Visa Acceptance Simplified

You may want to see also

Catholicism and the Third Reich

Background

In the 1930s, around a third of Germans were Catholic, most of them living in Southern Germany, while Protestants dominated the north. The Catholic Church in Germany opposed the Nazi Party, and in the 1933 elections, the proportion of Catholics who voted for the Nazis was lower than the national average. Hitler and several key Nazis were raised as Catholics but became hostile to the Church as adults. Article 24 of the National Socialist Program called for conditional toleration of Christian denominations, and the 1933 Reichskonkordat treaty with the Vatican guaranteed religious freedom for Catholics. However, the Nazis sought to suppress the power of the Catholic Church in Germany.

Persecution of the Church

Catholic press, schools, and youth organizations were closed, property was confiscated, and about one-third of its clergy faced reprisals from the authorities. Catholic lay leaders were among those murdered during the Night of the Long Knives. During the rule of the Nazi regime, the Church frequently found itself in a difficult position, with the Church hierarchy in Germany trying to work with the new government. However, Pope Pius XI's 1937 encyclical, Mit brennender Sorge, accused the government of hostility towards the Church.

Catholic Resistance

Despite the risks, some Catholics resisted the Nazi regime. Catholics fought on both sides during World War II, and Hitler's invasion of predominantly Catholic Poland ignited the conflict in 1939. In the Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, as well as in the annexed regions of Slovenia and Austria, Nazi persecution of the Church was intense, and many Polish clergy were targeted for extermination. Through his links to the German Resistance, Pope Pius XII warned the Allies about the planned Nazi invasion of the Low Countries in 1940. The Nazis gathered dissident priests in a dedicated barracks at Dachau concentration camp, where 95% of its 2,720 inmates were Catholic, and over 1,000 priests died there.

Complicity and Silence

While there were acts of resistance, the Catholic Church as an institution did not openly oppose the Third Reich. Even as the Church hierarchy attempted to tread delicately to avoid destruction, actively resisting priests sometimes acted against the express instructions of their superiors to found groups that sought to influence the course of the war in favour of the Allies.

Post-War Guilt and Complicity

After the war, the silence of the Church leadership and the complicity of ordinary Christians compelled Catholic leaders to address issues of guilt and complicity during the Holocaust, a process that continues to this day.

Joining the Bavarian Illuminati: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Bavaria's distinct culture

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a state in the southeast of Germany. It has a distinct culture, largely because of its Catholic heritage and conservative traditions, which includes a language, cuisine, architecture, festivals and elements of Alpine symbolism.

The Bavarian culture (Altbayern) has a long and predominant tradition of Roman Catholic faith. In 1925, 70.0% of the Bavarian population was Catholic, 28.8% was Protestant, 0.7% was Jewish, and 0.5% was placed in other religious categories. As of 2020, 46.9% of Bavarians adhered to Catholicism (a decline from 70.4% in 1970). Bavarians commonly emphasize pride in their traditions. Traditional costumes collectively known as Tracht are worn on special occasions and include Lederhosen for males and Dirndl for females. Centuries-old folk music is performed. The Maibaum, or Maypole, and the bagpipes of the Upper Palatinate region bear witness to the ancient Celtic and Germanic remnants of the cultural heritage of the region.

Bavarians tend to place a great value on food and drink. In addition to their renowned dishes, Bavarians also consume many items of food and drink which are unusual elsewhere in Germany; for example, Weißwurst ("white sausage") or in some instances a variety of entrails. At folk festivals and in many beer gardens, beer is traditionally served by the litre (in a Maß). Bavarians are particularly proud of the traditional Reinheitsgebot, or beer purity law, initially established by the Duke of Bavaria for the City of Munich in 1487 and the duchy in 1516. According to this law, only three ingredients were allowed in beer: water, barley, and hops. Bavarians are also known as some of the world's most prolific beer drinkers, with an average annual consumption of 170 liters per person.

Bavaria is also home to the Franconia wine region, which has produced wine (Frankenwein) for over 1,000 years and is famous for its use of the Bocksbeutel wine bottle. The production of wine forms an integral part of the regional culture, and many of its villages and cities hold their own wine festivals (Weinfeste) throughout the year.

Three German dialects are most commonly spoken in Bavaria: Austro-Bavarian in Old Bavaria (Upper Bavaria, Lower Bavaria, and the Upper Palatinate), Swabian German (an Alemannic German dialect) in the Bavarian part of Swabia (southwest) and East Franconian German in Franconia (north). In the small town of Ludwigsstadt in the north, Thuringian dialect is spoken. During the 20th century, an increasing part of the population began to speak Standard German (Hochdeutsch), mainly in the cities.

The Alps and Bavaria: Where Do They Intersect?

You may want to see also