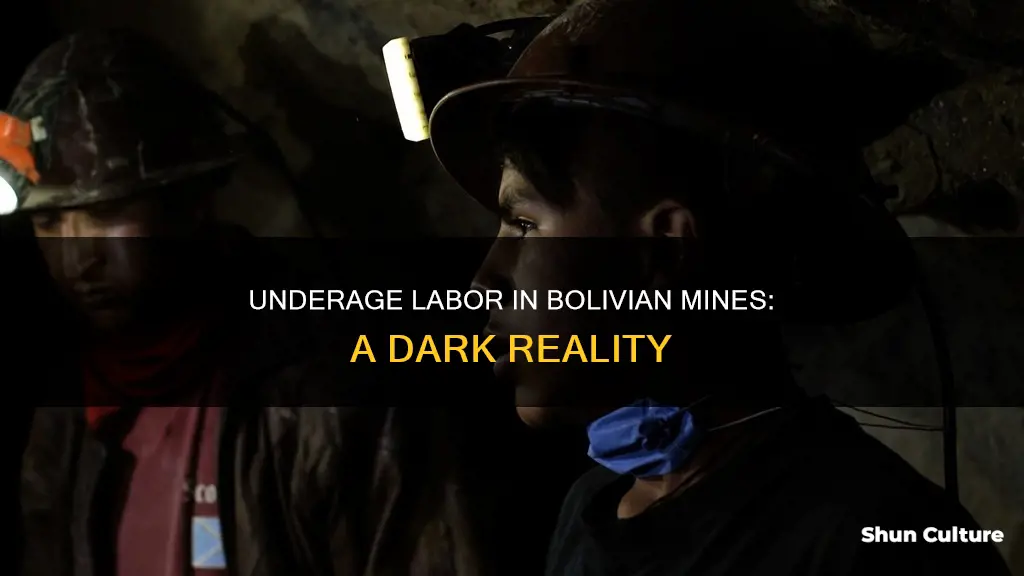

Bolivia is known for its dangerous mines, where children as young as 6 work alongside adults. In 2013, it was reported that there were 3,000 child miners in Bolivia, with some sources stating that this number has risen in recent years. The country has lowered the legal working age to as young as 10, with parental consent, and children from the age of 12 can work under contract. The Bolivian government justifies this by stating that the law recognises the harsh reality of the country, where 42% of the population is poor and children are often expected to support their families. However, this puts Bolivia at odds with the International Labour Organization, which stipulates 14 as the minimum working age for developing countries.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of underage workers in mines | 3,000 |

| Age range | 6-16 |

| Age of youngest worker | 6 |

| Average life expectancy of boy miners | 35 |

| Number of children working in gold and silver mines in Potosí, Oruro and La Paz | 7,000 |

| Year in which the Bolivian government passed Law No. 548 on "Ninos y ninas y adolescentes Trabajadores" | 2014 |

| Minimum age of workers established by Law No. 548 | 12 |

What You'll Learn

Children as young as 6 work in Bolivia's mines

In Bolivia, child labour is a reality, with an estimated one in three children working. While the exact number of underage workers in the mines is unknown, it is estimated that thousands of children as young as 6 years old are working in these dangerous environments.

A journalist reporting on the issue claimed that around 3,000 children work in Bolivia's mines, with some as young as 6. In 2008, 60 of these children died from accidents inside the mines. The average life expectancy of miners in one mine in Bolivia is about 35 years due to the high prevalence of silicosis, a respiratory disease caused by inhaling crystalline dust raised during drilling.

Bolivia has a long history of mining, dating back to the 14th century when the Incas first operated the mines. The country is rich in natural resources, with valuable deposits of silver, tin, zinc, gold, and copper. The Cerro Rico mine in Potosí, in particular, has been called one of the most dangerous mines in the world. It has been in operation for over 400 years and was once the richest source of silver in the Americas.

Children often work alongside their fathers or other family members in the mines, helping to support their families financially. They may work long hours, pushing carts to move rocks and minerals out of the mines. The work is physically demanding and dangerous, with young miners suffering injuries and even death.

The Bolivian government has recognized the severity of the issue, categorizing mining as one of the worst forms of child labour due to its negative impact on children's health and education. In 2014, the government passed Law No. 548, "Ninos y ninas y adolescentes Trabajadores," to protect and regulate child labour. Despite these efforts, poverty and family disintegration continue to drive children into the mines, and the enforcement of labour laws remains a challenge.

Exploring Miles: Bolivia to Jax Beach Road Trip

You may want to see also

Children are paid $3 a day to work in the mines

In Bolivia, children as young as six are permitted to work, with an estimated one in three children in employment. While the minimum working age is 14, exceptions are made for less dangerous jobs. However, this policy is poorly enforced, and it is estimated that almost a quarter of a million Bolivian children between the ages of 7 and 14 are working, many in the mining industry.

In the Bolivian city of Potosí, children are paid $3 a day to work in the mines. Abigail Canaviri, 14, is one such child. She works in the Cerro Rico mine, the world's highest, following in her late father's footsteps. She says, "They pay me 20 bolivianos (about $3) per day to scavenge through 10 or 12 mine carts. I enter at 6 pm and leave at 4 or 5 in the morning." Abigail is one of several dozen children who work in the mine, alongside 12,000 adults.

The children work in dangerous conditions, with little protection from accidents or the inhalation of harmful dust. They often join their fathers or other family members in the tunnels, and the money they earn helps support their families. The average life expectancy of a boy who works in the mine is just 35 years, due to the high incidence of silicosis, a respiratory disease caused by inhaling crystalline dust.

Despite the dangers, some children in Bolivia are campaigning for the working age to be lowered, so that their labour can be regulated and they can be protected in the same way as adult workers. The Bolivian government has recently passed a law to protect and regulate child labour, but the country's deep poverty means that, for many families, child labour is a necessity.

The mines in Potosí have been in operation for centuries, and the entire economy of the city, with its 250,000 inhabitants, is dependent on the industry. The miners work to extract silver, tin, zinc, and gold from the mountains. The work is gruelling and often deadly, with miners dying in cave-ins and accidents.

GPS in Bolivia: Does It Work?

You may want to see also

Children work in the mines to support their families

In Bolivia, an estimated one in three children work, and some face the danger of working in the country's mines. In 2013, a journalist reported that there were 3,000 children working in Bolivian mines, some as young as 6 years old.

Children as young as 11 years old work long hours in the mines, often joining their fathers or other family members in the tunnels. They are usually tasked with pushing carts to move rocks out of the mines. This work takes a toll on their childhood, as they have little time to play and be carefree.

Bolivia has a history of child labour, and the issue is deeply entrenched in the country's mining industry. In 2018, the Bolivian government lowered the legal working age from 14 to 10 years, hoping to regulate the labour conditions of children in dangerous jobs. Despite this, there are still children working below the legal age.

The future looks bleak for these child miners, who are caught in a cycle of poverty and dangerous working conditions. The average life expectancy for boy miners is only about 35 years due to the prevalence of silicosis, a respiratory disease caused by inhaling crystalline dust during drilling.

Exploring the Tasty Delights of Bolivian Cuisine

You may want to see also

Children work long hours and are often tasked with pushing carts

In Bolivia, children as young as 6 years old work long hours in the mines, often joining their fathers or other family members in the tunnels. They are tasked with pushing carts to move rocks, minerals, and ore out of the mines. The work is gruelling and relentless, and the children are not provided with any protective gear besides a helmet.

Photographer Simone Francescangeli, who documented the lives of miners in the city of Potosí, observed that boys sometimes work extremely long hours and are often put to work pushing carts. He noted that the children long to play and be carefree, but their harsh lives in the mines rarely permit this.

One 15-year-old boy, Santiago, described his typical day working in the mines. He uses his small body to reach tight spaces and break up rocks, which he then pushes through a gap to an older miner waiting in the mineshaft below. Once the rail cart is full, Santiago and the older miner push and pull it back through the narrow tunnel to the outside. Santiago then shovels out the contents of the cart, repeating this cycle throughout the day.

Abigail Canaviri, 14, works in the same mine as Santiago. She earns 20 bolivianos (about $3) per day to search through 10 to 12 mine carts. She enters the mine at 6 pm and leaves between 4 and 5 am. Canaviri and her young friends are aware of the dangers, but they have few options as they seek to break free from the cycle of poverty affecting their families.

Child labour is a pervasive issue in Bolivia, with an estimated one in three children working. While the legal working age in the country is 14, the law is not well-enforced, and exceptions are made for less hazardous occupations. According to the US Department of Labour, nearly a quarter of a million Bolivian children between the ages of 7 and 14 are employed, and many of them work in mining.

Exploring El Alto, Bolivia: Altitude and Its Impact

You may want to see also

Bolivia's government is taking measures to reduce child labour

Child labour is a significant issue in Bolivia, with an estimated one in three children working. In 2013, it was reported that around 3,000 children worked in the country's mines, some as young as six years old. While Bolivia has ratified key international conventions concerning child labour, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, and its laws prohibit forced labour and all forms of violence against children, the issue persists due to factors such as poverty and a lack of access to education. However, the Bolivian government is taking measures to address this problem and protect children's rights.

Firstly, Bolivia has established a National Commission for the Progressive Eradication of Child Labour, which coordinates national efforts to tackle this issue. This commission includes representatives from various ministries, such as justice, education, and planning, as well as non-governmental organisations (NGOs). While the effectiveness of this commission has been questioned due to a lack of public reporting on its activities, it demonstrates the government's recognition of the problem and its commitment to finding solutions.

Secondly, the Bolivian government has implemented policies and social programs aimed at eliminating child labour. For example, the Juancito Pinto Subsidy Program provides conditional cash transfers to primary and secondary school students to increase school attendance and reduce dropout rates. Additionally, the Bolivian Foreign Trade Institute's Triple Seal Initiative is a voluntary certification program that recognises companies complying with Bolivian law and International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions on child labour and forced labour issues. These initiatives show that the government is trying to address the root causes of child labour and incentivise businesses to uphold labour standards.

Thirdly, the government has taken steps to improve law enforcement and judicial processes related to child labour. Ministerial Resolution No. 1444/23 allows labour inspectors to conduct unannounced inspections at any time, which helps deter violations and ensures compliance with labour laws. Additionally, the government is working with civil society organisations, such as the Munasim Kullakita Foundation, and the police to address human trafficking and protect vulnerable children. The Alerta Juliana mobile application, for instance, helps locate missing children and refer them to authorities and protection services.

Finally, Bolivia has ratified the Safety and Health in Construction Convention (No. 167) of the ILO, demonstrating its commitment to improving work conditions and protecting the safety and health of workers, including minors, in the construction industry. This convention aims to prevent occupational diseases and accidents in a sector that is known for its dangers and the dispersion of responsibilities. By ratifying this convention, Bolivia has taken a significant step towards protecting workers' rights and ensuring safe working environments.

While child labour remains a challenge in Bolivia, the government's efforts to address it are noteworthy. Through a combination of coordination, policy implementation, social programs, improved law enforcement, and international cooperation, Bolivia is taking measures to reduce child labour and protect children's rights. However, further steps are needed to fully align with international standards and effectively enforce labour laws, especially in high-risk sectors like mining.

Bolivia: Safe Haven or Tourist Trap?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

It is difficult to give an exact number, but there are estimated to be thousands of underage workers in Bolivian mines. One source states that there are 3,000 children working in the mines, while another estimates that there are 7,000.

Children as young as 6 years old are reported to be working in the mines.

Working conditions in the mines are extremely dangerous, with children facing the risk of fatal accidents, respiratory diseases such as silicosis, and exposure to toxic chemicals. The air inside the mines is thin and claustrophobic, and there are few safety precautions in place.

Poverty and family disintegration are the main causes of child labour in the mines. Children often join their fathers or other family members in the mines to supplement their family income.

The Bolivian government has passed laws to protect and regulate child labour, and is taking measures to reduce it. UNICEF is also supporting the government in this effort by providing bonuses to families whose children attend school regularly.