The Bavarian dialect is a group of Upper German varieties spoken by approximately 12 million people across an area of around 125,000 square kilometres. It is the largest of all German dialects and is spoken in the German state of Bavaria, most of Austria, and the Italian region of South Tyrol. The Bavarian dialect is divided into three subgroups: Northern Bavarian, Central Bavarian, and Southern Bavarian. Each of these subgroups has distinct accents and variations in pronunciation and vocabulary. While Standard German is widely used in education and the media, Bavarians have a strong sense of unity and cultural identity associated with their dialect, leading to efforts to preserve and promote it through various initiatives and events.

What You'll Learn

- The Bavarian dialect is spatially divided into South Bavarian, Central Bavarian, and North Bavarian

- Bavarians often feel a stronger sense of unity with their homeland than with Germany

- The Bavarian dialect is considered a cultural asset worthy of protection

- The Bavarian dialect is in decline

- The Bavarian dialect is distinct from standard German

The Bavarian dialect is spatially divided into South Bavarian, Central Bavarian, and North Bavarian

The Bavarian dialect is spatially divided into three subgroups: South Bavarian, Central Bavarian, and North Bavarian. These subgroups differ noticeably from each other, and in Austria, they often coincide with the borders of particular states. For example, the accents of Carinthia, Styria, and Tyrol can be easily recognised as distinct from one another.

South Bavarian

South Bavarian or Southern Bavarian is a cluster of Upper German dialects of the Bavarian group. They are primarily spoken in Tyrol (the Austrian federal state of Tyrol and the Italian province of South Tyrol), in Carinthia, and in the western parts of Upper Styria. Before 1945 and the expulsions of Germans, it was also spoken in speech islands in Italy and Yugoslavia. Due to the geographic isolation of these Alpine regions, many features of the Old Bavarian language from the Middle High German period have been preserved. The Southern Bavarian dialect area is influenced by the Rhaeto-Romance languages, as well as Slovene and, to a lesser extent, Italian.

South Bavarian has eight vowels and about 33 consonants. The core area of the conservative Southern Bavarian dialect lies outside of Bavaria, in Tyrol and Carinthia. The preservation of affricates (a plosive followed by a fricative) in 'Kchua' for "Kuh" (cow) and the distinction of d- and t- in the initial sound of the word in 'do' for "hier" (here), 'tuat' for " [er] tut " ([he] does) are typical of this dialect.

Central Bavarian

Central Bavarian is spoken along the main rivers Isar and Danube, in Upper Bavaria (including Munich, which has a standard German-speaking majority), Lower Bavaria, southern Upper Palatinate, the Swabian district of Aichach-Friedberg, the northern parts of the State of Salzburg, Upper Austria, Lower Austria, Vienna, and the Northern Burgenland. The "vocalisation" of l after a vowel, usually into an i sound, is characteristic of this dialect: [håitn] for "halten" (to hold), and 'Stui' for "Stuhl" (chair). This is one of a series of linguistic innovations that characterise Central Bavarian but have not always advanced to the periphery of Northern and Southern Bavarian. Most of these changes reached Bavaria from Vienna up the Danube.

North Bavarian

North Bavarian or Northern Bavarian is mainly spoken in the Upper Palatinate and the adjacent areas of Upper and Middle Franconia. In the south, it reaches as far as the Danube. The dropped diphthongs ej, and ou for Middle High German ie, and uo, as in 'Brejf' (Southern and Central Bavarian 'Briaf') for "Brief" (letter) or 'Bou' (Southern and Central Bavarian 'Bua') for "Bub" (boy), are characteristic of this dialect. In terms of vocabulary, North Bavarian is conservative; words like 'Mädlein' ('Moidl', etc.) for "Mädchen" (girl), 'Himbeere' (raspberry), and 'Tote' for "Patin" (godmother) have been retained instead of new Central Bavarian innovations like 'Dirndl', 'Hohlbeere', and 'Godn'. The pronunciation of North Bavarian also lacks any new developments such as the Central Bavarian vocalisation of -l.

Combining Bavarian and Whipped Cream: A Delicious Dessert Duo?

You may want to see also

Bavarians often feel a stronger sense of unity with their homeland than with Germany

The basics of the Bavarian language landscape can be broken down into three different language areas: Swabian, Franconian, and Bavarian. However, it is important to note that there is not one single Franconian or Bavarian language. For example, within the Bavarian language, there are Upper, Middle, and Lower Bavarian dialects.

The Bavarian people's strong sense of unity and connection to their homeland is often reflected in their language. This sense of unity can even be observed in the smallest details of their culture. For instance, in Lower Franconia, neighbouring villages have a tradition of trying to steal each other's May poles. This friendly rivalry has led to the development of unique idioms in neighbouring communities.

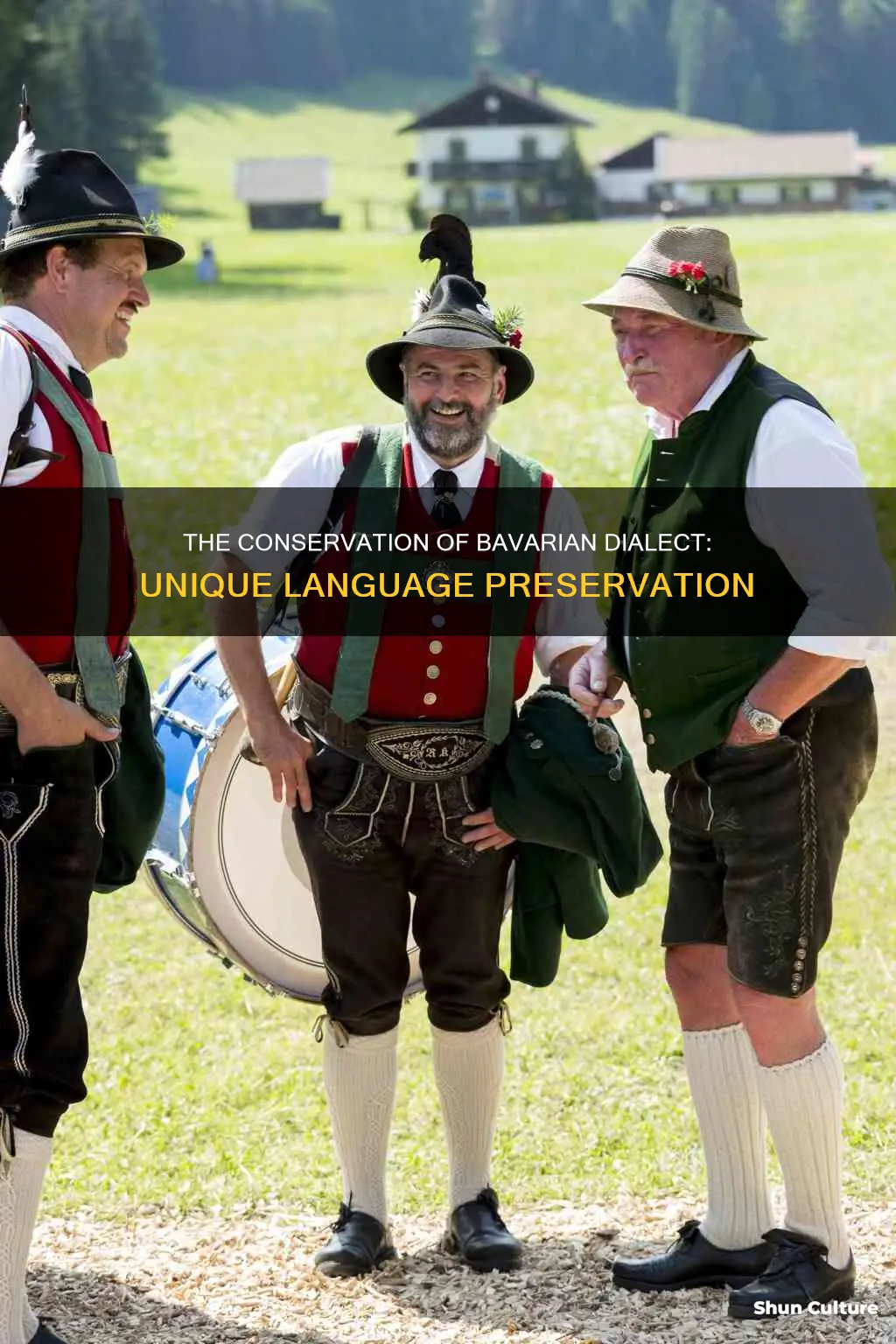

The Bavarian dialect has been deliberately cultivated and preserved over the years, and it is considered a valuable cultural asset. Various institutions, associations, and awards have emerged to promote and protect the Bavarian dialect and all the dialects spoken in Bavaria.

Bavaria's linguistic tradition has developed over centuries, and it is an important part of the region's culture and history. The first surviving traditions and poems in the Bavarian vernacular date back to the 8th century AD. The Bavarian dialect has continued to evolve, with the successful history of the Bavarian dukes and kings contributing to the growth of the language area.

The preservation of the Bavarian dialect is also linked to the emergence of the German state. In the 16th century, the German state helped spread High German, a purely written language, into everyday use. However, the Bavarian dialect has maintained its prominence in Bavaria, with many inhabitants still speaking and identifying with it.

Make Bavarian Sauerkraut: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

The Bavarian dialect is considered a cultural asset worthy of protection

The history of the Bavarian language dates back to around 100 AD when the first Teutons from the North settled in the region, bringing their Proto-Germanic language with them. Over the centuries, these Germanic tribes mixed with the Celto-Roman Boii already living in the area, resulting in the Germanic-Celtic Bavarian tribe. The first surviving traditions and poems in the Bavarian vernacular date from the 8th century AD, and since then, the dialect has been divided into Upper, Middle, and Lower Bavarian.

Today, Bavaria's linguistic tradition is being cultivated more intensively and deliberately than ever before. Numerous institutions, associations, and awards have emerged to preserve the Bavarian dialect and all the dialects spoken in the region. For example, there is the Förderverein Bairische Sprache und Dialekte e.V. association, a Bavarian Dialect Award, and the annual Bavarian Dialect Day in Deggendorf.

Bavaria's dialects are also being promoted through educational initiatives. The current curricula in schools demand that pupils be introduced to the appropriate use of the different language forms, especially in the context of teaching German. Additionally, politics is discussing educational initiatives to help establish the Bavarian language more in people's everyday lives.

Bavaria and Germany: One and the Same?

You may want to see also

The Bavarian dialect is in decline

There are several factors contributing to the decline of the Bavarian dialect. One factor is the emergence and spread of High German, a purely written language that became prevalent in the 16th century. High German is taught in schools as the standard language, and with increased education, more people are adopting it in their everyday lives. Additionally, society's increased mobility and internationalization have made it easier for people to move between regions, leading to a mix of dialects and a potential loss of distinct regional languages.

The Bavarian dialect is also facing competition from other languages and dialects in the region. In Bavaria, various dialects are spoken, including Frankish, Swabian, and Alemannic. These dialects influence each other and can lead to a mix of pronunciations and words, making it difficult to preserve the purity of the Bavarian dialect.

Another factor contributing to the decline is the lack of written standardization for the Bavarian dialect. While there have been efforts to promote the use of the dialect, such as the establishment of the Förderverein Bairische Sprache und Dialekte association and the Bavarian Dialect Award, the lack of a standard writing system makes it challenging to use Bavarian in formal settings like education and literature. As a result, Bavarian is primarily a spoken language, and even then, it is mostly used in rural areas and within families that regularly speak the dialect.

The decline of the Bavarian dialect is concerning for those who view it as a valuable cultural asset. The dialect has a long history, dating back to the 8th century, and it has played a significant role in shaping the identity of Bavarians. Efforts are being made to preserve and promote the dialect, such as through educational initiatives and cultural events like the annual Bavarian Dialect Day. However, it remains to be seen if these efforts will be enough to halt the decline and ensure the survival of the Bavarian dialect for future generations.

Brewing Bavarian Coffee: My Cafe's Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

The Bavarian dialect is distinct from standard German

Bavarian is a group of Upper German dialects spoken in the south-east of the German language area, including the German state of Bavaria, most of Austria, and the Italian region of South Tyrol. It is also spoken in parts of Brazil, Canada, and the United States.

Bavarian has about 60 different variants, with regional differences that are sometimes unintelligible even to other Bavarians. For example, a village 10km away from one source's hometown used entirely different words and pronunciations for numbers.

Bavarian has its own grammatical quirks and unique words that do not exist in standard German. For example, the word "horglig" does not exist in standard German. Bavarian also has an extensive vowel inventory, with vowels grouped as back rounded, front unrounded, and front rounded.

Bavarian is the largest of all German dialects, with approximately 12 million speakers across 125,000 square kilometres. In 2008, 45% of Bavarians claimed to use only the dialect in everyday communication. However, Bavaria and Austria officially use Standard German as the primary medium of education. As a result, younger people, especially in urban areas, tend to speak Standard German with only a slight accent.

Despite the prevalence of Standard German in education and the media, the Bavarian dialect is still in daily use in its region and is considered a cultural asset worthy of protection by many in the political community.

Dunkin's Bavarian Cream Powder: A Sweet, Easy-to-Use Treat

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

There are over 60 dialects in Bavaria.

Examples of Bavarian dialects include Upper, Middle and Lower Bavarian, Northern Bavarian, Central Bavarian, and Southern Bavarian.

Some characteristics of the German dialect spoken in Munich are that R is often trilled, "schauen" is more common than "gucken", and "hinauf" and "hinunter" are shortened to "'nauf" and "'nunter".

The history of the Bavarian language as we know it today starts around 100 AD when the first Teutons from the North settled in today's Bavaria. They brought their Proto-Germanic language with them to a Latin language area still influenced by the strong Roman rule. Over the next few centuries, the Germanic tribes mingled with the Celto-Roman Boii already living there, gradually resulting in the Germanic-Celtic style Bavarian tribe.

The Bavarian dialect is conserved through various initiatives and organisations such as the Förderverein Bairische Sprache und Dialekte e.V. association, the Bavarian Dialect Award, and the annual Bavarian Dialect Day in Deggendorf. Additionally, educational initiatives are being discussed to help establish the Bavarian language in people's everyday lives.