Bolivia, a landlocked country in South America, has faced significant challenges in ensuring access to clean water for its citizens. In 2016, the country experienced its worst drought in decades, affecting thousands of families and agricultural lands. While the government has made efforts to improve water planning and management, issues such as melting glaciers, mining activities, and the impacts of climate change continue to threaten Bolivia's water supply. The country has also grappled with privatization and contamination issues, leading to protests and a push for better government oversight. Despite these challenges, Bolivia is making progress toward its goal of providing clean water access to its entire population, with increasing investment in water infrastructure and sanitation systems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Population | 11.05 million |

| Rural access to basic water services | 78% |

| Rural access to basic sanitation services | 36% |

| Urban water access | 97% |

| Rural water access | 76% |

| Urban sanitation access | 61% |

| Rural sanitation access | 28% |

| Water committees | Common |

| Water sources | Aquifers, glacial supplies, rainwater |

| Water issues | Drought, mining, climate change, pollution, contamination, shrinking glaciers |

| Water security initiatives | WEAP, Water For People, Water Ministry, "Water for Life" law |

What You'll Learn

Bolivia's water sources

Bolivia's drinking water and sanitation coverage has improved since 1990, yet the country still has the lowest coverage levels and the lowest quality of service on the continent. In 2015, 90% of the population had access to "improved" water, and 50% had access to "improved" sanitation. However, Bolivia's water sources are under threat from a number of factors, including drought, melting glaciers, mining, and pollution.

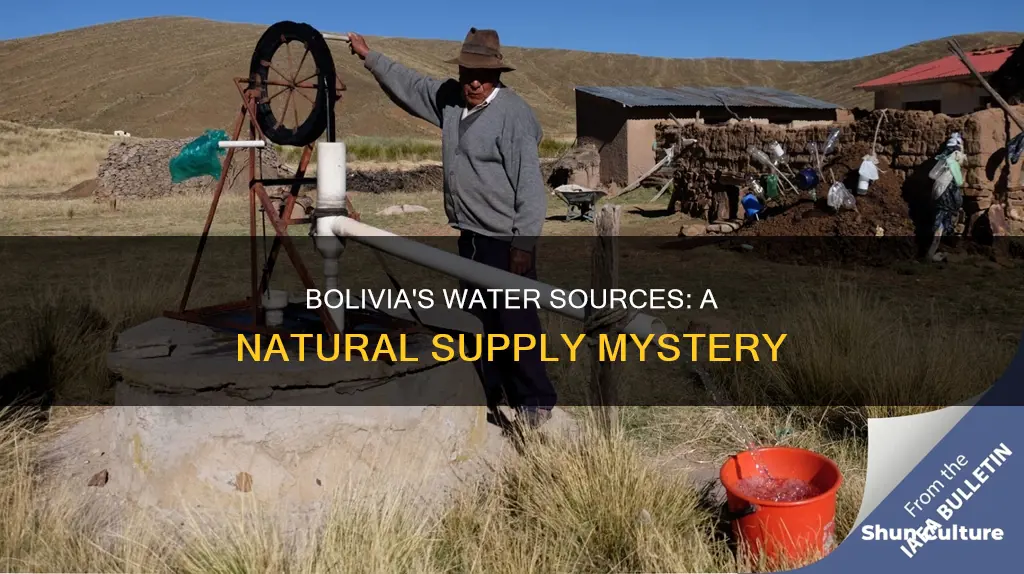

In certain regions of Bolivia, people depend on water from aquifers. One key aquifer is Purapurani, which supplies water to the cities of El Alto and Viacha, near the capital of La Paz. In 2016, Bolivia suffered its worst drought in 25 years, which led to water rationing in La Paz and El Alto. The drought affected 125,000 families and threatened 290,000 hectares of agricultural land. The country's water sources are also threatened by melting glaciers. Bolivian cities get some of their water from glacial supplies, especially during dry months, and critics argue that the government has failed to secure alternative water sources. More than 40% of Bolivia's glaciers have melted in the last 20 years.

Mining has also contributed to water depletion in Bolivia. For example, large-scale gold extraction has been blamed for swallowing and polluting the Desaguadero River, which fed Lake Poopó, once Bolivia's second-largest lake. In addition, countless truckloads of public water have been sold to mining firms. Furthermore, foreign mines near one of La Paz's reservoirs have been accused of sucking up the water supply.

To address these issues, the Bolivian government has taken several steps. Under the leadership of President Evo Morales, the government has allocated millions of dollars to resolve water scarcity concerns. The government has also established the Water Ministry and nominated a leader of the protests in El Alto against water privatisation as the country's first water minister. In addition, Bolivia has implemented the Water Evaluation and Planning (WEAP) tool, which helps the country plan for the future by creating a comprehensive model of its water sources. The government has also worked with the IAEA to establish an isotope hydrology laboratory to assess water resources and determine their origin, age, vulnerability to pollution, movement, and interactions.

La Paz, Bolivia: Fire Department Presence and Preparedness

You may want to see also

Water access and sanitation

Bolivia has made significant strides in improving access to drinking water and sanitation services since 1990, thanks to increased sectoral investments. However, the country still faces challenges in this sector. As of 2015, 90% of the total population had access to "improved" water, with higher access in urban areas (97%) compared to rural areas (76%). Regarding sanitation, 50% of the total population had access to "improved" sanitation facilities, with urban residents having better access (61%) than their rural counterparts (28%).

One of the main issues in the water and sanitation sector in Bolivia is low access to sanitation and water in rural areas. For example, as of 2017, more than three million people in rural areas lacked access to clean water, resulting in gastrointestinal illnesses from contaminated water sources. To address this, Bolivia has implemented initiatives like the Water Evaluation and Planning (WEAP) tool, which helps the government anticipate and plan for future water security needs by providing detailed information about the country's water resources. Additionally, Bolivia has invested in establishing water and sanitation offices (DMSBs) in districts to support communities with the operation, maintenance, and oversight of water services.

The quality of water and sanitation services in Bolivia is also a concern. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), only 26% of urban water systems disinfected their water, and merely 25% of the collected wastewater was treated in 2000. Political and institutional instability have further weakened the sector's institutions, hindering long-term sustainable policy-making.

To promote better sanitation practices, Bolivia has adopted a market-based approach, encouraging families to invest in their own household toilets that meet their specific needs and preferences. Additionally, programs like the one in the district of Villa Rivero, which covers 10-20% of a family's bathroom construction costs, have helped increase the demand for better sanitation in rural areas. Microfinance initiatives for sanitation improvements also enable families to access small loans to build improved bathrooms.

Bolivia's water supply is threatened by various factors, including melting glaciers, mining activities, and droughts. The country's glaciers have receded by over 40% since 1985, impacting water availability, especially during dry months. Droughts, such as the one in 2016, have severe consequences for both urban and rural areas, leading to water rationing and affecting agriculture.

Bolivia's COVID-19 Vaccine Requirements for Entry

You may want to see also

Water security and climate change

Bolivia is among the countries most affected by climate change, which impacts its water cycle. This is reflected in increasing water scarcity, floods, prolonged droughts, and other extreme weather events. The Bolivian government is keen to address the growing water crisis and water conflicts by managing water resources more efficiently and in a climate-sensitive manner.

The government, with support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and the European Union (EU), is implementing a national plan for water catchment areas. This plan focuses on the strategically important basins of the Río Azero and the Río Guadalquivir, where water management strategies are being developed to reduce water risks. The project also strengthens the technical and organizational capabilities of the national and regional governments, administrative units, municipalities, and civil society.

One of the key strategies to improve water security in Bolivia is to protect and sustainably use water from aquifers, such as the Purapurani aquifer, which supplies water to the cities of El Alto and Viacha near La Paz. Nuclear technology has been instrumental in helping scientists understand the age, quality, and source of groundwater in these aquifers, enabling better planning and management of water resources.

The future water supply and demand for La Paz and El Alto, Bolivia, were estimated in a study, and it was found that the area is likely to face a serious water shortage after the mid-2020s, even with conserved demand. The study examined effective measures for adapting to water shortages, including water transfers from neighboring systems and the diversion of runoff into reservoirs.

Overall, Bolivia is taking important steps to improve water security and address the challenges posed by climate change. However, the country continues to suffer from low coverage levels and the quality of water services, and further efforts are needed to ensure sustainable water management and access for its population.

Chia Seeds from Bolivia: Are They Safe to Eat?

You may want to see also

Water politics and privatisation

Water politics in Bolivia has been a contentious issue, with the country suffering from the lowest coverage levels and low quality of water services on the continent. Political and institutional instability have contributed to the weakening of the sector's institutions at the national and local levels.

In the 1990s, the privatisation of water supply and sanitation took place during the second mandate of President Hugo Banzer. This took the form of two major private concessions: one in La Paz/El Alto to Aguas del Illimani S.A. (AISA), a subsidiary of the French company Suez, and another in Cochabamba to Aguas del Tunari, a subsidiary of the multinational corporations Biwater and Bechtel. These concessions were granted as a requirement to retain ongoing state loans from the World Bank and the International Development Bank.

The privatisation of water led to a significant increase in water prices, with rates in Cochabamba rising by an average of 35%. This sparked widespread protests, particularly from those in the poorest neighbourhoods, who were not connected to the network of water systems and had to pay even more for lower-quality water from trucks and handcarts. The protests, known as the "Cochabamba Water War" or "Bolivian Water War", culminated in the declaration of a national state of emergency and martial law, with violent clashes between protesters and the police.

In April 2000, a 17-year-old student, Víctor Hugo Daza, was shot in the face by the Bolivian Army while protesting. Following this incident, the national government reached an agreement with the Coordinadora (a community coalition) to reverse the privatisation. As a result, the two concessions were terminated, and public utilities replaced the private companies.

Despite the reversal of privatisation, Bolivia continues to face challenges in water management. In 2016, the country experienced its worst drought in 25 years, leading to water rationing and shortages in La Paz and El Alto. The government has been criticised for failing to secure alternative water supplies, with melting glaciers and mining activities contributing to the depletion of water sources.

To address these issues, the government of Evo Morales has taken steps to strengthen citizen participation in the water sector and plans to introduce a new water and sanitation services law called "Water for Life". However, increasing coverage and improving the quality of water services will require substantial investment financing.

Bolivia's Unique Attractions and Renowned Cultural Offerings

You may want to see also

Water committees and community action

Bolivia's water committees, or juntas, are a key feature of the country's water landscape. These committees are particularly prominent in rural areas, where they are responsible for operating and maintaining water systems.

The water committees emerged as a powerful force in Bolivia during the Water War in Cochabamba in 2000. This conflict was sparked by the privatisation of the city's drinking water and sanitation services, which were sold to the consortium Aguas del Tunari, controlled by the US company Bechtel. Bechtel increased water rates for Cochabambans by 35 to 50%, which was unaffordable for many, as it represented a significant proportion of their average monthly income. The conflict escalated, with thousands of inhabitants taking to the streets in protest, and the government declaring a state of siege. One 17-year-old boy was killed, and after several days of unrest, the Bechtel executives left Cochabamba, the privatisation law was revoked, and water supply was returned to public hands.

The Water War demonstrated the power of community action and the water committees as a tool for social empowerment. The committees played a crucial role in the fight for the right to water, and they continue to resist state efforts to centralise control of water resources. The committees are committed to keeping management of water resources at the community level, ensuring local control and autonomy.

The water committees bring together knowledge on water resource management, climatology, and emergency response. They transmit this knowledge to the wider community, fostering a strong awareness of water culture and promoting sustainable and participatory access to water.

In addition to their core focus on water, the water committees also address other issues that impact the community. For example, they may discuss members' well-being, security, festivities, and local events. This holistic approach to community development reflects the integral role that water plays in social life.

The water committees have had a significant impact on policy and governance in Bolivia. In 2006, Evo Morales became president, emphasising that "water cannot be a private business because it converts it into a merchandise and thus violates human rights. Water is a resource and should be a public service." Morales nominated a leader of the protests in El Alto against water privatisation as the country's first water minister, signalling a commitment to citizen participation in the sector.

The resilience and determination of Bolivia's water committees and community action have been instrumental in shaping the country's water landscape and ensuring access to this vital resource, despite ongoing challenges such as climate change, population growth, and the impacts of mining on water sources.

Bolivian Ram vs. Pearl Gourami: A Deadly Encounter?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bolivia gets water from a variety of sources, including aquifers, rivers, lakes, and glaciers. However, the country has been facing a water crisis due to shrinking glaciers, droughts, and management challenges.

The water crisis in Bolivia has led to water shortages, with thousands of people affected and protests breaking out in cities like La Paz. It has also resulted in a decline in agricultural output and threatened the livelihoods of farming communities.

The Bolivian government has implemented several measures to address the water crisis, including allocating funds to resolve water scarcity, improving water planning and management, and collaborating with international organizations to develop tools like the Water Evaluation and Planning (WEAP) tool to improve water security.