The term Prussian has historically been used to refer to the inhabitants of Prussia, a former German state centred on the North European Plain. However, in Bavarian slang, the term Prussian or Preissn is used derogatorily to refer to non-Bavarians, specifically those from northern Germany. So, to answer the question 'how do you say Prussian in Bavarian?', one would simply say Preissn.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Bavarian slang for non-Bavarians | Prussian |

| Bavarian word for Northern Germans | Preißn |

| Bavarian word for Austrians | Schluchtenscheißer or Ösi |

| Bavarian word for Italians | Norditaliener |

| Bavarian word for non-Bavarian Germans | Saupreißn |

| Bavarian word for non-Bavarian Germans (offensive) | Pirfke |

| Bavarian word for non-Bavarian Germans (offensive) | Fischkoobf |

| Bavarian word for non-Bavarian Germans (offensive) | Breiß |

| Bavarian word for Northern Germans (offensive) | Saubreiss |

| Bavarian word for Northern Germans (offensive) | Mistbreiss |

| Bavarian word for Northern Germans (offensive) | Nordliacht |

What You'll Learn

The Bavarian dialect

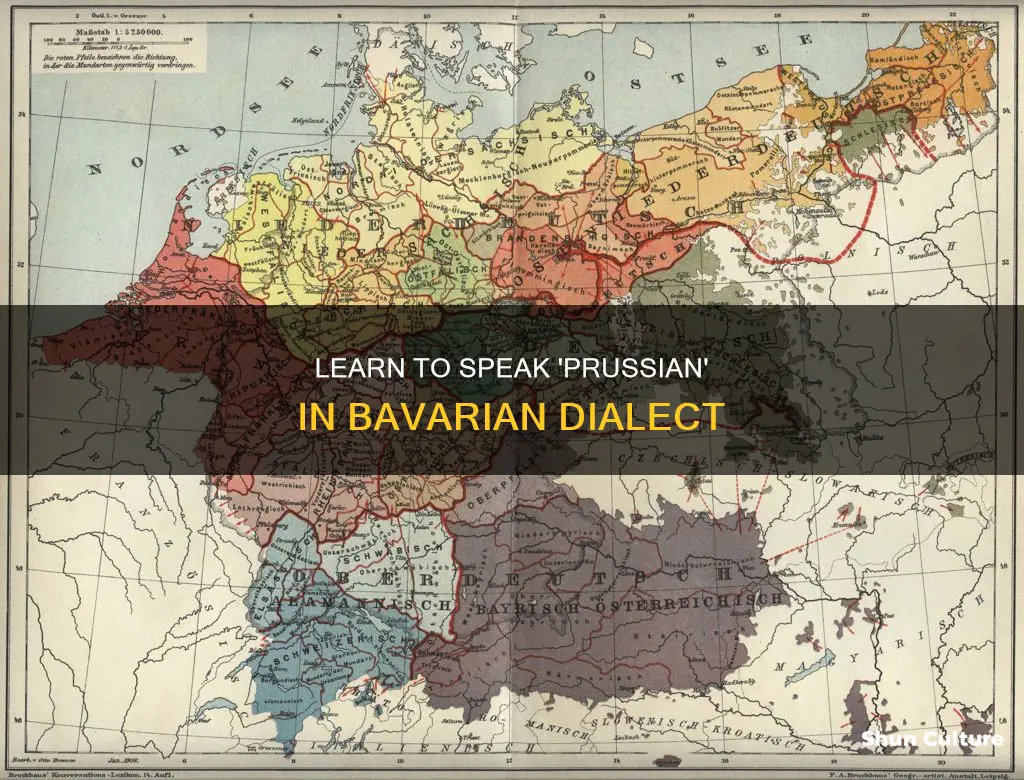

Bavarian, or Austro-Bavarian, is a dialect of German spoken in the south-east of the German language area. It is prevalent in the German state of Bavaria, most of Austria, and the Italian region of South Tyrol. It is also spoken in parts of Brazil, Canada, Italy, Hungary, Switzerland, and the United States. It is the largest of all German dialects, with around 12 million speakers.

Bavarian is considered a dialect of German, but some classify it as a separate language. The International Organization for Standardization has given it a unique language code, and UNESCO lists it as an endangered language. However, some scholars criticize its classification as an individual language.

Bavarian is primarily a spoken language, and many Bavarian terms are spelled phonetically. It has three main dialects: Northern Bavarian, Central Bavarian, and Southern Bavarian. There are also said to be about 60 different variants. The differences between these dialects can be extreme, and even Bavarians struggle to understand each other at times.

Bavarian has its own alphabet, which includes additional vowel sounds not heard in standard German. The Bavarian "a", for example, can be a long, drawn-out "a" that sounds more like an "o", or a short, bright "a". The "o", in turn, is pronounced more like a light "a".

Bavarian has its own greetings, such as "Seavus" or "Servus" for "hello", and "Pfiate" for "goodbye". It also has unique phrases, such as "a Maß" for "a litre of beer", and "Vo is as glo?" for "where is the restroom?".

Bavarians are proud of their dialect and appreciate it when foreigners attempt to pronounce words correctly. They are also known for their strong sense of belonging and often identify as Bavarians rather than Germans.

Technic's Touch: Reprogramming a New Battery

You may want to see also

Prussian history

Prussian is Bavarian slang for non-Bavarians. The history of Prussia, however, is a long and complex one.

Prussia was a German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularisation of the Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. The Teutonic Knights were an organised Catholic medieval military order of German crusaders who conquered the lands inhabited by the Old Prussians, whose language belonged to the Baltic group of the Indo-European language family. The Prussian countryside was subdued, castles were built for German nobility, and many German peasants were settled there to farm the land. By the middle of the 14th century, the majority of the inhabitants of Prussia were German-speaking.

In 1525, the Teutonic Order's last grand master in Prussia, Albert of Hohenzollern, became a Lutheran and secularised his fief, transforming it into a duchy for himself. This territory, known as Ducal Prussia, was ruled by the Hohenzollern dynasty until 1618, when it was inherited by John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg. The union of Ducal Prussia with Brandenburg was fundamental to the rise of the Hohenzollern monarchy to the rank of a great power in Europe.

In 1701, Frederick, Elector of Brandenburg, crowned himself "King in Prussia" as Frederick I. The other Hohenzollern possessions soon came to be treated as belonging to the Prussian kingdom rather than as distinct from it. In 1772, Prussia annexed most of the Polish province of Royal Prussia, allowing Frederick to finally adopt the title "King of Prussia".

Prussia continued its rise to power, especially during the reign of Frederick II, known as "Frederick the Great", who ruled from 1740 to 1786. He put the newly realised strength of the Prussian state at the service of an ambitious foreign policy, invading Silesia and thereby beginning the War of the Austrian Succession. Prussia's victories in the ensuing Silesian Wars established its dominant role among the German states and as a European great power.

Prussia was the driving force behind the unification of Germany in 1866 and was the leading state of the German Empire until its dissolution in 1918. Prussia made attempts to unify all the German states under its rule, and whether Austria would be included in such a unified domain was an ongoing question. After the Napoleonic Wars, the issue of unifying the German states caused the German revolutions of 1848-1849, with representatives from all states attempting to unify under their own constitution.

Prussia was subsequently the driving force behind the North German Confederation, transformed in 1871 into the unified German Empire. The German Empire successfully unified all of the German states aside from Austria and Switzerland under Prussian hegemony due to the defeat of Napoleon III in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871.

With the German Revolution of 1918-1919, the Kingdom of Prussia was transformed into the Free State of Prussia. Prussia as a whole was abolished in 1947.

Bavarian Food: A Cultural Culinary Experience

You may want to see also

The Kingdom of Prussia

In 1525, Grand Master Albert of Brandenburg-Ansbach, a member of a cadet branch of the House of Hohenzollern, became a Lutheran Protestant and secularised the Order's remaining Prussian territories into the Duchy of Prussia. This was the area east of the mouth of the Vistula River, later sometimes called "Prussia proper". For the first time, these lands were in the hands of a branch of the Hohenzollern family, who already ruled the Margraviate of Brandenburg to the west, a German state centred in Berlin. Furthermore, with his renunciation of the Order, Albert could now marry and produce legitimate heirs.

Brandenburg and Prussia were unified two generations later. In 1594 Duchess Anna of Prussia, granddaughter of Albert I and daughter of Albert Frederick, Duke of Prussia (reigned 1568–1618), married her cousin Elector John Sigismund of Brandenburg. When Albert Frederick died in 1618 without male heirs, John Sigismund was granted the right of succession to the Duchy of Prussia, which was still a Polish fief. From this time the Duchy of Prussia was in personal union with the Margraviate of Brandenburg. The resulting state, known as Brandenburg-Prussia, consisted of geographically disconnected territories in Prussia, Brandenburg, and Rhenish lands of Cleves and Mark.

During the Thirty Years' War, the disconnected Hohenzollern lands were repeatedly marched across by various armies, especially the occupying Swedes. The ineffective and militarily weak Margrave George William (1619-1640) fled from Berlin to Königsberg, the historic capital of the Duchy of Prussia, in 1637. His successor, Frederick William I (1640-1688), reformed the army to defend the lands.

Frederick William went to Warsaw in 1641 to render homage to King Władysław IV Vasa of Poland for the Duchy of Prussia, which was still held in fief from the Polish crown. Later, he managed to obtain a discharge from his obligations as a vassal to the Polish king by taking advantage of the difficult position of Poland vis-á-vis Sweden in the Northern Wars and his friendly relations with Russia during a series of Russo-Polish wars. He was finally given full sovereignty over Prussia in the Treaty of Wehlau in 1657.

On 18 January 1701, Frederick William's son, Elector Frederick III, upgraded Prussia from a duchy to a kingdom, and crowned himself King Frederick I. To avoid offending Leopold I, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire where most of his lands lay, Frederick was only allowed to title himself "King in Prussia", not "King of Prussia". However, Brandenburg was treated in practice as part of the Prussian kingdom rather than a separate state.

The Great Elector had incorporated the Junkers, the landed aristocracy, into the kingdom's bureaucracy and military machine, giving them a vested interest in the Prussian Army and compulsory education. King Frederick William I inaugurated the Prussian compulsory conscription system in 1717.

In 1740, King Frederick II (Frederick the Great) came to the throne. Using the pretext of a 1537 treaty (vetoed by Emperor Ferdinand I) by which parts of Silesia were to pass to Brandenburg after the extinction of its ruling Piast dynasty, Frederick invaded Silesia, thereby beginning the War of the Austrian Succession. After rapidly occupying Silesia, Frederick offered to protect Queen Maria Theresa if the province were turned over to him. The offer was rejected, but Austria faced several other opponents in a desperate struggle for survival, and Frederick was eventually able to gain formal cession with the Treaty of Berlin in 1742.

To the surprise of many, Austria managed to renew the war successfully. In 1744 Frederick invaded again to forestall reprisals and to claim, this time, the Kingdom of Bohemia. He failed, but French pressure on Austria's ally Great Britain led to a series of treaties and compromises, culminating in the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle that restored peace and left Prussia in possession of most of Silesia.

Humiliated by the cession of Silesia, Austria worked to secure an alliance with France and Russia (the "Diplomatic Revolution"), while Prussia drifted into Great Britain's camp forming the Anglo-Prussian Alliance. When Frederick preemptively invaded Saxony and Bohemia over the course of a few months in 1756–1757, he began a Third Silesian War and initiated the Seven Years' War.

This war was a desperate struggle for the Prussian Army, and the fact that it managed to fight much of Europe to a draw bears witness to Frederick's military skills. Facing Austria, Russia, France, and Sweden simultaneously, and with only Hanover (and the non-continental British) as notable allies, Frederick managed to prevent a serious invasion until October 1760, when the Russian army briefly occupied Berlin and Königsberg. The situation became progressively grimmer, however, until the death in 1762 of Empress Elizabeth of Russia (Miracle of the House of Brandenburg). The accession of the Prussophile Peter III relieved the pressure on the eastern front. Sweden also exited the war at about the same time.

Defeating the Austrian army at the Battle of Burkersdorf and relying on continuing British success against France in the war's colonial theatres, Prussia was finally able to force a status quo ante bellum on the continent. This result confirmed Prussia's major role within the German states and established the country as a European great power. Frederick, appalled by the near-defeat of Prussia and the economic devastation of his kingdom, lived out his days as a much more peaceable ruler.

Other additions to Prussia in the 18th century were the County of East Frisia (1744), the Principality of Bayreuth (1791) and Principality of Ansbach (1791), the latter two being acquired through purchase from branches of the Hohenzollern dynasty.

Prussia was subsequently the driving force behind establishing in 1866 the North German Confederation, transformed in 1871 into the unified German Empire and considered the earliest continual legal predecessor of today's Federal Republic of Germany. The North German Confederation was seen as more

Heidelberg: Bavaria's Gem or Not?

You may want to see also

Prussian culture

The Kingdom of Prussia was ruled by the House of Hohenzollern for centuries, and they expanded its size with the Prussian Army. The kingdom was decisive in shaping the history of Germany, especially after it united the German states in 1871 to form the German Empire. The kingdom ended in 1918 along with other German monarchies that were terminated by the German Revolution.

Prussian virtues, which were derived from the kingdom's militarism and the ethical code of the Prussian Army, include loyalty, self-denial, bravery, subordination, courage, obedience, discipline, sincerity, modesty, honesty, straightforwardness, sense of justice, conscientiousness, willingness to make sacrifices, sense of order, sense of duty, punctuality, probity, cleanliness, frugality, tolerance, incorruptibility, restraint, determination, and reliability. These virtues were criticised for their remoteness from science and art, their hostility to democracy, and their association with militarism and state control.

The legacy of Prussia is still evident today in various aspects of German life, including the use of certain symbols, the preservation of cultural institutions, and the continuation of traditions in diplomacy and the military.

Bavarian Filled Donuts: Vegetarian-Friendly or Not?

You may want to see also

Prussian language

The term 'Prussian' has a variety of meanings and connotations, including imperialism and militarism, and can refer to a geographical region, a political state, or the people and language of that region.

The Prussian Language

Prussian, or Old Prussian, is an extinct West Baltic language that belonged to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European languages. It was once spoken by the Old Prussians, the Baltic people of the Prussian region. The language is called Old Prussian to differentiate it from the German dialects of Low Prussian and High Prussian, and from the adjective Prussian, which relates to the later German state.

Old Prussian is thought to have begun being written down in the Latin alphabet around the 13th century, and a small amount of literature in the language survives from this period. The language experienced a 400-year decline after the Teutonic Knights conquered the region in the 13th century, leading to an influx of Polish, Lithuanian, and German speakers. Old Prussian likely ceased to be spoken around the beginning of the 18th century due to famine and disease.

Old Prussian is closely related to other extinct West Baltic languages, including Sudovian, West Galindian, and possibly Skalvian and Old Curonian. It is also related to the East Baltic languages Lithuanian and Latvian, and more distantly to Slavic languages. Old Prussian had loanwords from Slavic languages, as well as some borrowings from Germanic, Gothic, and Scandinavian languages.

Prussian as a Slang Term

In Bavarian slang, 'Prussian' is used to refer to non-Bavarians, and the term carries a negative connotation. This usage may stem from historical differences between Bavaria and Prussia, with Prussia often being associated with imperialism and militarism, while Bavaria maintained a more relaxed culture.

Learning Prussian

Due to the limited knowledge and documentation of Old Prussian, it is challenging to find comprehensive resources for learning the language. However, some enthusiasts have reconstructed and revived the language based on historical sources, and there are now families that use Old Prussian as their first language. There are also various online resources, dictionaries, learning apps, and games available for those interested in exploring this extinct language.

Bavaria's Beer: A Unique Brew?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

"Preißn" or "Saupreißn" are the Bavarian terms for 'Prussian'.

'Preißn' is a derogatory term used by Bavarians to refer to anyone who isn't Bavarian, including Northern Germans and non-Bavarian German speakers.

The term 'Preißn' historically referred to the inhabitants of Prussia, a German state that originated in 1525 and was dissolved in 1947.

The term is spelled 'Preißn' and pronounced 'pr-ice-n'.