The origins of World War I can be traced back to the tensions between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, which eventually exploded into a global conflict. The roots of this animosity lay in the complex dynamics of the Balkan region, where competing national and imperial ambitions clashed. Austria-Hungary, a multi-ethnic empire, viewed Serbia as a threat to its stability due to its aspirations to unite the Slavic peoples of the region. Serbia's growing nationalism and alignment with Russia, a rival of Austria-Hungary, further fuelled tensions. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, by a Serbian-backed terrorist in 1914 became the catalyst for war. Austria-Hungary, with German encouragement, issued an ultimatum to Serbia, intending to provoke a conflict. Serbia's refusal to accept all the demands led to Austria-Hungary declaring war, marking the beginning of World War I.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reasoning behind Austria-Hungary's ultimatum to Serbia | Austria-Hungary wanted to crush the Serbian threat once and for all. |

| Austria-Hungary's intention behind the ultimatum | Austria-Hungary intended to start a war with Serbia. |

| Austria-Hungary's expectation from the ultimatum | Austria-Hungary expected Serbia to reject the ultimatum, giving them an excuse to invade. |

| Austria-Hungary's reaction to Serbia's response | Austria-Hungary rejected Serbia's response, which conceded to all the ultimatum's demands except one. |

| Result of the ultimatum | Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on July 28, 1914, starting World War I. |

| Austria-Hungary's goal during the war | Austria-Hungary aimed to eliminate Serbia as a threat and punish it for fuelling South Slav irredentism in the Monarchy. |

| Austria-Hungary's actions during the war | Austria-Hungary committed war crimes, including massacres, hostage-taking, and destruction of villages. |

| Serbia's response to the war | Serbia resisted the invasion and launched counterattacks, inflicting defeats on Austria-Hungary. |

| Impact of the conflict | The war resulted in the occupation and denationalization of Serbia, with severe repercussions for its civilian population. |

What You'll Learn

Austria-Hungary's ultimatum to Serbia

On the evening of July 23, 1914, nearly a month after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, the Austro-Hungarian ambassador to Serbia, Baron Giesl von Gieslingen, delivered an ultimatum to the Serbian foreign ministry. The ultimatum was issued with the full support of Austria-Hungary's allies in Berlin, who had been working in coordination with the German foreign office to force a military conflict. The plan was to end the conflict quickly and decisively with a crushing Austrian victory before the rest of Europe, particularly Serbia's powerful ally, Russia, had time to react.

The ultimatum demanded that the Serbian government:

- Formally and publicly condemn the "dangerous propaganda" against Austria-Hungary, which aimed to detach territories belonging to the Monarchy.

- Suppress all publications that "incite hatred and contempt of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy" and are "directed against its territorial integrity".

- Dissolve the Serbian nationalist organisation Narodna Odbrana ("The People's Defence") and all other such societies in Serbia.

- Eliminate without delay from schoolbooks and public documents all "propaganda against Austria-Hungary".

- Remove from the Serbian military and civil administration all officers and functionaries whose names the Austro-Hungarian government will provide.

- Accept in Serbia "representatives of the Austro-Hungarian Government" for the suppression of subversive movements and allow them to take part in the investigations of the Archduke's assassination.

- Arrest Major Vojislav Tankosić and civil servant Milan Ciganović, who were named as participants in the assassination plot.

- Cease the cooperation of the Serbian authorities in the "traffic in arms and explosives across the frontier"; dismiss and punish the officials of Šabac and Loznica frontier service, "guilty of having assisted the perpetrators of the Sarajevo crime".

- Provide "explanations" to the Austro-Hungarian government regarding "Serbian officials" who have expressed themselves in interviews "in terms of hostility to the Austro-Hungarian Government".

- Notify the Austro-Hungarian Government "without delay" of the execution of the measures comprised in the ultimatum.

The ultimatum gave Serbia 48 hours to comply with these demands. If no "unconditionally positive answer" was received within the deadline, the Austro-Hungarian Minister in Belgrade was instructed to leave the embassy with all its personnel.

The ultimatum caused a stir in foreign capitals. British officials described it as "the most insolent document of its kind ever devised", and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov declared that no state could accept such demands without "committing suicide". Despite the severity of the ultimatum, Serbia's reply, delivered by Prime Minister Nicola Pasic just before the deadline, accepted all terms except the demand that Austro-Hungarian officials be allowed to operate in Serbia, stating that this would violate the Constitution and the law of criminal procedure. This response appealed to international observers, but it made little difference to Vienna, and on July 28, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, marking the beginning of World War I.

Austria's Blush: Wesley Snipes and the Art of Embarrassment

You may want to see also

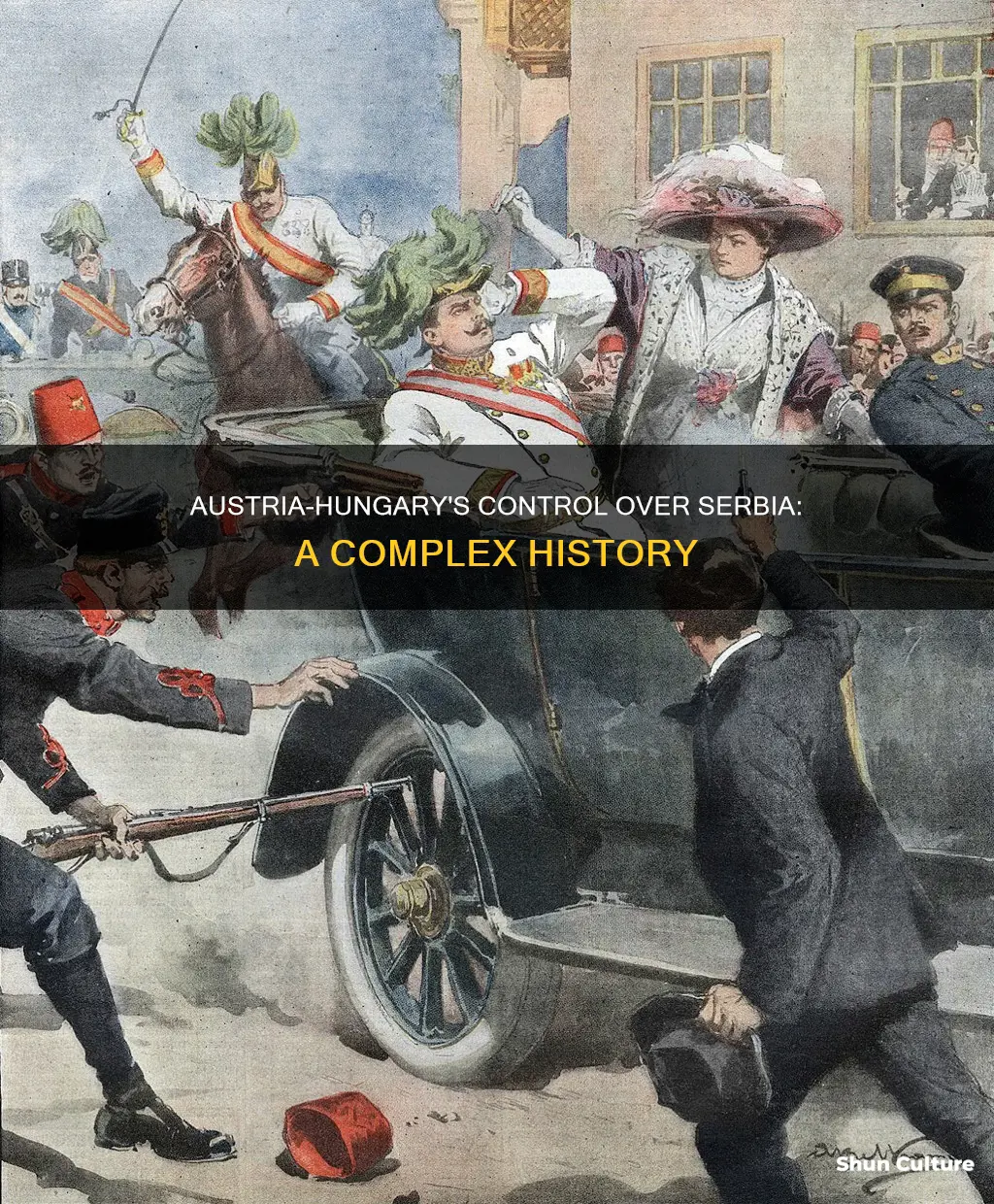

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Princip was part of a group of six Bosnian assassins, five of whom were Bosnian Serbs and members of a student revolutionary group that later became known as Young Bosnia. The political objective of the assassination was to free Bosnia and Herzegovina of Austria-Hungarian rule and establish a common South Slav ("Yugoslav") state. The assassins were aided by the Black Hand, a Serbian secret nationalist group with close ties to the Serbian army.

The assassination of the Archduke and his wife was the culmination of a series of events that began with Austria-Hungary's annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908, against the wishes of neighboring Serbia, which likewise coveted these provinces. This annexation strained relations between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, and led to a series of conflicts, including the "Pig War" and the Bosnian crisis of 1908-1909. Serbia's military successes and Serbian outrage over the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina emboldened Serbian nationalists in Serbia and Serbs in Bosnia who chafed under Austro-Hungarian rule.

In the years leading up to the assassination, there were several unsuccessful assassination attempts against Austro-Hungarian officials by lone assassins, mostly Serb citizens of Austria-Hungary. In the spring of 1914, a second plot against the Archduke emerged when Princip and his fellow Young Bosnia member, Nedeljko Čabrinović, learned of the Archduke's planned visit to Bosnia in June. They recruited four other assassins and, with the help of the Black Hand, acquired bombs, pistols, and other supplies.

On the morning of June 28, 1914, the assassins fanned out along the motorcade route in Sarajevo. Čabrinović threw a bomb at the Archduke's car, but it bounced off and exploded under the wrong vehicle, wounding several people but leaving the Archduke and his wife unharmed. Čabrinović was apprehended, while the other assassins failed to act. The motorcade proceeded to the Town Hall, where the Archduke gave a speech.

After the event at the Town Hall, the Archduke and his wife got back into their car to visit the wounded from the bombing at the hospital. However, due to a miscommunication, the driver of their car turned onto a side street where Princip was standing. Princip stepped up to the car and shot the Archduke and his wife at point-blank range. The Archduke and his wife died within minutes of each other.

CBD Legality in Austria: What's the Current Status?

You may want to see also

Serbian nationalism and pan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism, a movement that emerged in the mid-19th century, sought to promote unity and integrity among the Slavic peoples. It particularly resonated in the Balkans, where South Slavs had been ruled by empires such as Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Venice for centuries. The movement was influenced by Romantic nationalism, emphasising language, race, culture, religion, and customs as hallmarks of national identity.

Serbian intellectuals played a significant role in the Pan-Slavic movement. They advocated for the independence of Slavic peoples within the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires and sought to unite all Southern Balkan Slavs, regardless of religious differences. Serbia, having recently gained independence from the Ottoman Empire, was a small but ambitious state. Its aspirations to unify the Slavic people of the region clashed with Austria-Hungary's desire to maintain control over its multi-ethnic empire.

Austria-Hungary's annexation of Bosnia in 1908 further strained relations. The Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, in which Serbia emerged as a larger and more assertive power, heightened Austria-Hungary's fears of Serbian nationalism. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, by the Bosnian Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip in June 1914, provided the spark that ignited the conflict. Austria-Hungary, with encouragement from its ally Germany, used this event as a pretext to issue an ultimatum to Serbia, intending to crush Serbian nationalism and assert its dominance in the region.

The Pan-Slavic movement had a significant impact on the course of events leading up to World War I. It fuelled Serbian aspirations for unity among the Slavic peoples and clashed with Austria-Hungary's desire to maintain control over its diverse empire. This ideological conflict, combined with rising nationalism and imperial rivalries, set the stage for the outbreak of war in 1914.

Exploring Austria: Planning Your Next Holiday Getaway

You may want to see also

Austria-Hungary's economic dominance over Serbia

Economic Exploitation:

Serbia's economy was exploited through confiscations, requisitions, and the utilisation of its economic resources and labour. Special units called "Suchdetaschement" were responsible for extensive requisitions of materials such as wool, copper, brass, nickel, and zinc, as well as food and leather. These resources were sent to an administrative body in Belgrade and then transported to Austria-Hungary. The exploitation of mines in Serbia also occurred, but it failed to satisfy the Dual Monarchy's needs fully due to Germany taking a significant portion as reparations for its military aid.

Agricultural Exploitation:

Serbia's agricultural sector was targeted to feed the occupying troops and support the war effort. Austria-Hungary aimed to make Serbia its "breadbasket." This led to food rationing and shortages for the Serbian population, causing famine and desperation.

Forced Labour and Deportations:

Serbia's population was subjected to forced labour, with thousands of men, women, and children deported to internment camps in Austria-Hungary. These deportations aimed to prevent insurgent activities and provide a labour force for the Austro-Hungarian war machine. The exact number of deportees is unknown, but estimates range from 150,000 to 200,000.

Denationalisation and Depoliticisation:

The occupational authorities implemented measures to suppress Serbian national consciousness, which was seen as a threat to the Empire. They banned public gatherings, political parties, and the Cyrillic script in schools and public spaces. Serbian cultural institutions, such as the Royal Serbian Academy and the National Museum, were closed and looted. The educational system was overhauled, with Serbian students forced to be educated in German and according to Austrian academic standards.

Economic Administration:

Serbia was divided into occupation zones, with the Austro-Hungarians controlling the northern three-quarters of the country. This area was ruled by the Military General Governorate of Serbia (MGG/S), established by the Austro-Hungarian Army. The MGG/S aimed to integrate Serbia as a part of the Empire under direct military rule, with political participation prohibited to prevent the emergence of a new Serbian state.

In summary, Austria-Hungary's economic dominance over Serbia was multi-faceted and aimed at exploiting the country's resources, labour, and economy while suppressing Serbian national identity. The measures implemented during the occupation had devastating consequences for Serbia's population and contributed to the country's struggle for independence during and after World War I.

Skiing in Austria: May Options

You may want to see also

Austria-Hungary's invasion of Serbia

The second campaign was launched under German command on October 6, 1915, almost a year after the first attempt. This time, Bulgarian, Austro-Hungarian, and German forces, led by Field Marshal August von Mackensen, successfully invaded Serbia from three sides. This resulted in the Great Retreat through Montenegro and Albania and the evacuation to Greece, with Serbia eventually falling and being occupied and divided between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Bulgaria.

The roots of the conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia can be traced back to several factors, including the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the contest for power in the Balkans, and the complex network of alliances between European powers. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, by a Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, provided the immediate catalyst for the invasion. Austria-Hungary suspected Serbian government involvement and used this incident as a pretext to curb Serbian ambitions in the region.

Additionally, both Austria-Hungary and Serbia had their sights set on acquiring territories from the collapsing Ottoman Empire, increasing tensions between the two nations. Austria-Hungary's annexation of Bosnia in 1908 and Serbian ambitions to unify Southeast Europe's Slavic people further strained their relationship. The Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 also played a role, as Serbia emerged as a larger and more assertive power in the region, alarming Austria-Hungary.

The complex network of alliances between European powers further escalated the conflict. Austria-Hungary turned to its powerful ally, Germany, for support, and on July 5, 1914, Kaiser Wilhelm II promised Germany's "faithful support" in the event of a conflict with Serbia. This assurance emboldened Austria-Hungary to issue an ultimatum to Serbia on July 23, 1914, which was largely rejected, providing the casus belli for the invasion.

The invasion of Serbia by Austria-Hungary had far-reaching consequences and marked the beginning of World War I, drawing in Russia, Germany, France, and the British Empire. The defeat of Serbia and its occupation by the Central Powers temporarily gave them mastery over the Balkans, opening a land route from Berlin to Constantinople and allowing the resupply of the Ottoman Empire. However, the Serbian forces, though exhausted and poorly equipped, displayed remarkable resilience, and their liberation in 1918 played a significant role in the final victory of World War I.

France's Declaration of War on Austria: The Historical Context

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Austria-Hungary and Serbia had a tense relationship. Serbia was sandwiched between Austria-Hungary and other states previously controlled by the Ottoman Empire. The two nations had competing interests in the Balkans, and Austria-Hungary saw Serbia as a threat to the stability of its multi-ethnic empire.

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife on June 28, 1914, by a Serbian-backed terrorist was the immediate cause of the conflict. Austria-Hungary suspected Serbian government involvement and used this event as a pretext to issue an ultimatum to Serbia.

The ultimatum included ten demands, the most significant being that Serbia accept Austrian officials to suppress subversive movements and allow them to participate in the investigation of the assassination. Serbia's refusal to meet all the demands led to Austria-Hungary declaring war on July 28, 1914, marking the beginning of World War I.

The conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia had far-reaching consequences. Austria-Hungary occupied Serbia from late 1915 until the end of World War I, committing various war crimes and atrocities against the Serbian population. The war also led to the occupation and division of Serbia into zones governed by Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria, with Germany taking control of key economic resources.